From Sisyphus to Zombies: How Our Fear of Eternity Is Reflected in Culture

Writer, director, and creative writing instructor from Berkeley, David Andrew Stoler, reflected in Aeon on why the image of the zombie consistently evokes fear in people, what modern tales of the undead have in common with ancient Greek myths, and what we truly fear more—death or eternal life.

Have you noticed that zombies have taken over the world (unless, of course, you are one of them)? The walking dead appear on your TV, online, and even in London’s East End. While thousands of dissertations today explore the theme of “eternal life” as an expression of our fear of surrendering our souls to technology, the terror of zombies appeared five thousand years before smartphones.

And it’s not just the zombies’ relentless desire to eat you alive, which is usually presented as the main reason for our fear. Zombies belong to a category of monsters that reappear throughout history—from ancient Mesopotamian myths to modern science fiction—because they evoke a horror even greater than the fear of violent death: the fear of the threat of “eternal life.”

Apeirophobia: The Fear of the Infinite

Apeirophobia—the fear of the infinite or the eternal—might seem laughable at first. After all, since ancient times, human societies have been full of tales and myths about people seeking “eternal life.” Yet these stories always reflect a hidden fear of what immortality might actually entail. The dead, whom the Babylonian goddess of fertility threatened to release from the underworld, didn’t crave brains but good food: the threat was that they would compete with the living, not eat them. The “great beyond” didn’t seem to have a dining hall; long before the concept of “the end of consciousness,” death meant a meager, miserable, eternal existence—like a never-ending flight on Spirit Airlines.

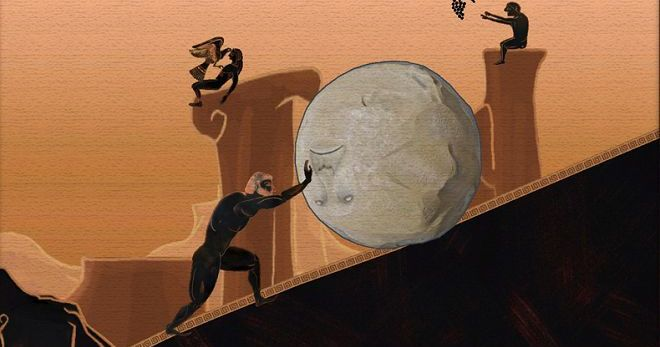

The Greeks also knew that “forever” is a mighty long time. For them, eternal life was an opportunity for truly Olympian-level sadism. Sisyphus, Tantalus, the poor Danaids—who simply refused to obey the gods and marry their cousins—were punished (as were many in Greek myths) not just with pain, hunger, and endless tasks, but with punishments that were necessarily endlessly repeating. It’s a grander version of our own daily nightmare: you might commute to work, sort paperwork, drive your kids to lunch—today and maybe tomorrow, again and again… But what if it was forever?

This is the torture for the apeirophobe: unbearable time, day after day, weaving a thread of the future whose length we can’t even imagine. In one interview, Richard Dawkins put it impossibly clearly:

“Our brains are not equipped to cope with [infinity].”

The very thought of it leads to existential despair, which can be traced in the works of Dante, Kafka, and even more terrifying incarnations created by modern authors.

The Universe and Our Place in It

Once people began to understand just how vast and old the universe really is, they had to face two things. First, the immeasurable. Second, humanity’s insignificant place within that immensity. For those who fear infinity, Major Tom (the fictional character created by David Bowie, featured in “Space Oddity” and “Ashes to Ashes,” as well as Peter Schilling’s “Major Tom (Coming Home)”) was not just a martyr of the space age: his tragedy, amplified in Schilling’s music, was that he would be “drifting, falling, floating, weightless” with no hope of ending his wandering. “No one understands, but Major Tom sees…” sings Schilling. What he sees, as he drifts further while being mourned on Earth, is endless light, loneliness, and the absoluteness of space.

In Stephen King’s short story “The Jaunt” (1981), this fear is even more pronounced. The plot follows a family making an instantaneous trip from Earth to Mars via teleportation. When the parents wake up on Mars, they discover their rebellious son skipped the special sleeping gas required to survive the “jaunt” (the teleportation process), and his consciousness experienced an endless journey. Infinite thoughts and boundless space turn the boy, as King writes, into “a creature older than time in the shape of a boy,” with “falling snow-white hair and impossibly ancient eyes.” The boy screams silently in the labyrinth of his long trip, literally driven mad by the infinity of time. This story is the apeirophobe’s worst nightmare.

Zombies as a Symbol of Eternal Torment

Zombies perfectly embody this horror. The chilling fact is that they are, essentially, us: every zombie once had their own life, woke up in the morning, drank coffee, worked with their wives in small diners, drove their kids to school—anything, before becoming a zombie. Just like the characters in Dante’s Inferno, they exist in a state that will last not just until the end of time, but beyond. A zombie trapped in this state will remain there forever, tormented by hunger—millennium after millennium. In other words, endlessly.

Time has no problem tricking us with such “entertainments.” A zombie doomed to wander the earth, or a character forced to listen to “I Wish it could be Christmas Every Day” for thousands and thousands of years—these are the scariest things an apeirophobe can face. That’s why the CIA uses time and repetition to torture people.

Being immortal, living forever—these ideas are no more than a teenager’s fantasy about endless riches and a wonderful life. Just imagine such an existence: everything around you dies, everyone you love, everything you know, soon enough—all of humanity, and after a while, the Earth itself, the galaxy, and then the universe. Most discussions about eternal life forget that the world itself isn’t going to last forever.

The other option, of course, is death. Not the most popular item on anyone’s bucket list. To die or to live forever: this paradox is the true version of soul-crushing horror. Being an apeirophobe means being eternally drained by this exhausting fear. A night filled with so many anxieties becomes unbearable. The fading evening sky and the endless blackness of the incomprehensibly vast universe make us involuntarily think about all of this. And these thoughts become destructive.

Because eternity has a bad ending. What could be scarier than living forever in a universe that will end in a billion-year dissolution into nothingness? I can’t imagine anything worse.

Zombies always resurrect this terrifying specter—again and again. Their insatiable hunger, their endless search, even their constant decay—a parallel to our own aging—beckon us to a world that waits forever, holding up a mirror in which there is no help for us, but where we can shudder and say:

“By the grace of a nonexistent god, we go.”