Echo Chambers Online: Why We’re Stuck in Our Own Bubbles

Adapted from a chapter of “Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World” by Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West (published by MIF). This article explores how and why our information space is narrowing, and why the information we receive and share is less about expanding knowledge and more about reinforcing social bonds.

One-Sidedness and Hyper-Bias in the Digital Age

Carl Bergstrom, PhD in Biology and professor at the University of Washington, studies how information spreads in biological and social systems. He believes, “Our world is awash in nonsense, and we’re drowning in it.” In his view, the era of big data is filled with misinformation, fake news, skewed statistics, and studies that prove nothing but are still presented as absolute truth.

How did this happen, and can we fight back against the flood of biased data overwhelming our information space? Bergstrom and Jevin West tackle these questions in their book, “Calling Bullshit: The Art of Skepticism in a Data-Driven World.” The authors examine all forms of “nonsense”—from statistical errors in science to unreliable information on TV and online—and explain how logic and critical thinking can help us find real value in the sea of information noise.

“…Back when news was a trickle, we could effectively evaluate the information we received. But now, we’re facing an avalanche.”

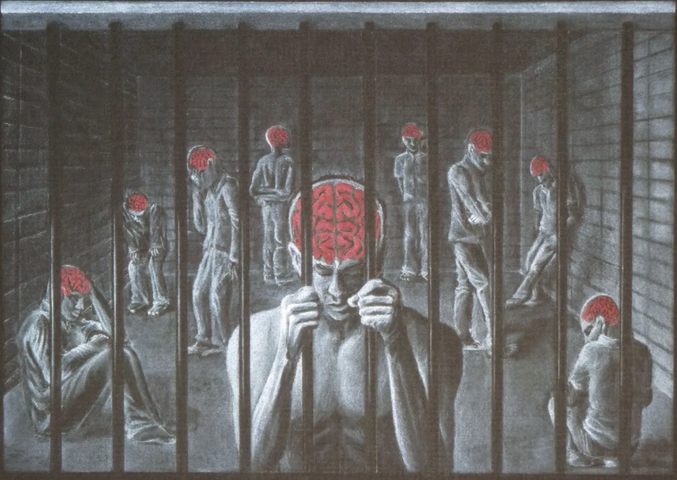

This chapter explores why the information we get and share on social media doesn’t broaden our horizons or foster true exchange, but instead serves to confirm, strengthen, and display our positions to maintain social ties. It also examines how algorithms show us content that matches their idea of our sociopolitical orientation, hiding alternative viewpoints and increasingly recommending more extreme and radical material—and why this is dangerous.

Bias, Personalization, and Polarization

Just as the invention of the printing press gave us a wider selection of books, the rise of cable TV allowed people to choose information channels that matched their views. Until 1987, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s “Fairness Doctrine” required balanced coverage of controversial issues in news programs. But it was repealed under President Ronald Reagan. Spurred by the birth of the 24-hour news cycle, cable news channels began to thrive and specialize in certain political leanings. Over the past twenty years, major U.S. news media have become increasingly one-sided in their reporting.

Online, the situation is even worse. Even leading news outlets rarely present information impartially. We end up in isolated echo chambers. Publishers like Breitbart News Network or The Other 98% go even further, producing news that is hyper-partisan. Their stories may be based on facts, but are so heavily filtered through an ideological lens that they often include significant falsehoods.

Publishers churn out one-sided, hyper-biased articles because they pay off. Social media favors ideological content. Such posts are shared more often than neutral news, and people are more likely to click on them. The intensification of political conflict has become a profitable business.

Signaling Identity Over Sharing Truth

MIT professor Judith Donath observed that when people talk about other things, they’re often really talking about themselves. For example, if I go on FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More and share an absurd conspiracy theory about airplane contrails being chemicals sprayed by liberals to lower testosterone in American youth, I’m less interested in convincing you and more interested in signaling my political beliefs. By sharing such an article, I’m showing that I belong to those who believe in conspiracy theories and distrust the “liberal agenda” in America. Whether the story is true or false doesn’t matter to me. I might not have even read it, and I don’t care if you do—I just want you to know I’m part of the tinfoil hat club.

The signal is the message. If I share a story about the IRS investigating Donald Trump’s pre-2016 business deals, my political leanings are unclear. But if I share a story claiming he sold the Washington Monument to Russian oligarchs, it’s obvious I hate Trump and am loyal enough to my group to suspend disbelief about his alleged misdeeds.

Donath’s insight comes from communication theory. We often think of communication as simply transmitting information from sender to receiver. But we ignore its broader aspect, captured by the Latin verb communicare—“to make common, to share.”

Communication is how we create, reinforce, and encourage our shared way of describing the world. Imagine a church service or a structured evening news broadcast. Social media communications are similar: they form and structure social groups. By tweeting, posting on FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, or uploading to Instagram, we affirm our commitment to the values and beliefs of a particular online community. The community responds, and these shared values are reinforced through likes, shares, comments, and retweets.

If I jump into a pool blindfolded and shout “Marco!” and do it right, my network of friends will respond in chorus: “Polo! Polo! Polo!” (In the U.S., “Marco Polo” is a pool game where the seeker, blindfolded, tries to find players who respond “Polo” when called “Marco.”) Sharing new information is a secondary goal when joining social networks. Their primary purpose is to maintain and strengthen social bonds. The danger is that public dialogue fragments so much in the process that it becomes impossible to restore. People fall into tribal epistemology, where the truth of a message depends less on facts and evidence and more on who delivers it and how well it fits the community’s worldview.

Algorithms Make It Worse

FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, Twitter, and other social platforms use algorithms to find “relevant” posts for you, personalizing your news feed. These algorithms aren’t designed to keep you informed—they’re designed to keep you engaged on the platform. Their goal is to feed you content that’s interesting enough to keep you from leaving for other sites or, heaven forbid, going to bed early. The problem is, algorithms create a vicious cycle, offering you more of what they think you want and limiting your exposure to other viewpoints. You don’t see how the algorithms work, but your likes, the posts you read, your friends list, your location, and your political preferences all influence what you see next. Algorithms highlight information that matches their idea of your sociopolitical orientation and suppress alternative perspectives.

On the internet, we’re all guinea pigs. Commercial sites constantly run large-scale experiments to see what keeps us online and increases engagement. Online media companies experiment with headlines, images, fonts, and even “Read More” button designs. Meanwhile, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More and other platforms offer advertisers—including politicians—the ability to target specific user groups with messages tailored to their interests. These messages aren’t always clearly marked as ads.

Think about what YouTube can learn by experimenting with video recommendations and watching what users choose. With billions of videos watched daily and massive computing power, the company can learn more about human psychology in a day than a scientist could in a lifetime. The problem is, their algorithms know only one way to keep viewers: recommend increasingly extreme content. Users who start with left-leaning videos are quickly steered toward far-left conspiracy theories. Those who prefer right-leaning content soon get recommendations for white supremacists or Holocaust deniers. We’ve seen this firsthand. While Jevin and his six-year-old son watched a live feed from the International Space Station, 254 miles above the round Earth, YouTube’s sidebar filled up with videos claiming the Earth is actually flat.

To paraphrase Allen Ginsberg, tech entrepreneur Jeff Hammerbacher complained in 2011: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.” The problem isn’t just that these “best minds” could be working for creative or scientific progress. All this intellectual power is being used to capture our precious attention and waste our mental energy. The internet, social media, and smartphones expose us to ever more sophisticated ways to distract ourselves. We become addicted to our connections, to mindlessly refreshing pages, to a life where our attention is scattered across countless streams of digital information. In short, the algorithms running social media are master manipulators. They don’t care what they show us—they just want to grab our attention and will serve up anything to keep it.