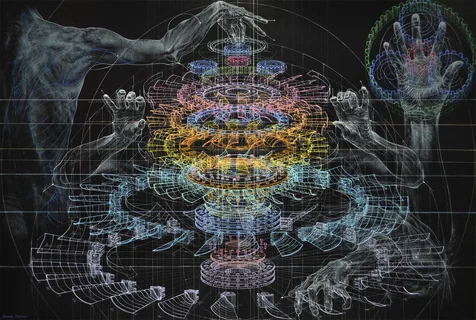

Structure of the Subjective World

Subjective Representation of the Structure of the Human Subjective World

This article explores how people internally represent values, intentions, criteria, abilities, the meaning of life, and more. The focus is on understanding the subjective structure of a person’s inner world.

Values

I’ll start with values, as most of the discussion will center around them. Research in this area also began with values. Here, it’s not so important how textbooks, Wikipedia, or training handouts define values. What matters is how you perceive them.

Why Values Matter

Values determine our goals, what we do or don’t do, and how we react to the actions of others. We also make decisions based on our values.

Becoming aware of and defining your own values can help you understand your actions, choices, and behaviors. Often, what seems important to us isn’t, and vice versa. This process also allows you to adjust your value system.

Defining Your Values

What are values to you? You need to come up with your own definition here.

Note: You can always change or clarify this definition later. For now, you just need a starting point.

- What determines my actions

- My guiding principles in this world

- What I want to strive for

- What is most important to me in the world

- What defines me as a person

- …and so on

In this and other exercises, focus on your own internal experience: if a quality, ability, mission, or behavior feels like a value to you, then it is a value for you.

Assessing Importance

Choose 5–7 things that are definitely values for you. Rate their importance on a scale from 0 to 10.

For example:

- Security — 9

- Friends — 9

- Justice — 6

- Respect — 5

- Personal growth — 10

- Love — 9

Later, you can compare these conscious ratings with those you get through calibration exercises.

Internal Representation

Now, let’s explore how your value system is represented internally. Take three values, preferably not from your previous list:

- One very important value

- One of medium importance

- One not very important

Don’t rely on logic here; focus on how you actually feel about them.

For example, you might choose:

- Freedom

- Precision

- Comfort

When you think about these values in terms of their importance, how do they appear to you? We need to identify their submodal characteristics.

When we think about values in the context of their relative importance, we often have a visual representation (though not always). You may notice that values feel different depending on how you think about them and may be represented in different modalities. But when you start thinking about them in terms of importance, they tend to align into a single system, which makes sense since it’s hard to compare a picture to a muscle sensation.

Values are usually organized by the principle of heterarchy—the importance of a specific value can change depending on the context. Hierarchy is like the military: general, colonel, major, lieutenant. Heterarchy is like a school class with no clear leader: one student is best at math, another at language, a third at sports, and a fourth sings best. In any given moment, heterarchy creates a hierarchy that changes with the situation.

For example:

- Values are arranged on a vertical line in front of you—the higher, the more important

- Importance is determined by distance—the closer, the more important

- Size matters—the bigger, the more important

- Brightness is linked to importance—the less important a value, the darker it appears

Pay attention to the critical submodality—the one that has the strongest influence. In your experience, as importance increases, a value might appear higher, brighter, and larger. But usually, one factor (size, brightness, contrast, etc.) is most significant.

Also, notice which metakinaesthetic cues show you the level of importance. The more important the value:

- The larger the area of sensation

- The stronger the feeling of expansion

- The warmer the sensation

- The faster the twisting movement

- The greater the amplitude of vibration

Now, check your logical ratings of values with self-calibration: scale your sense of importance—brightness, distance, heat intensity, height—and imagine where the values from your first list are for you, how you experience them.

Some people will find almost complete alignment with their logical ratings, others will find none, but usually there’s some overlap and some differences.

What Makes a Value a Value?

The next task is to figure out for yourself: what makes a value a value? How do emotions and values differ, for example: joy as an emotion and joy as a value?

Or consider a concept that isn’t a value for you, even if you view it positively (world peace, democracy, honor), versus a value-concept (security, equality).

It’s helpful to divide values into emotion-values (joy, happiness, comfort) and concept-values (justice, growth, freedom).

The self-modeling process is fairly standard: pick three or four “just emotions” and positive concepts, write them in a column, and look for what they have in common. Then, in another column, write three or four emotion-values and concept-values, and look for their commonalities.

The goal is to identify the characteristic features of the class, not just individual values, emotions, or concepts.

Then, look for differences between the columns. This could involve submodalities, metaprograms, qualities, concepts, and so on. Ideally, find the critical differences—what turns a value into just an experience, or vice versa.

Usually, values are experienced as something more “extended”: they exist in all contexts, are always present in your thoughts, and persist over time. In contrast, “just” emotions are short-lived and experienced in the moment.

Sources and Further Reading

- Our other channels

- Our friends and partners