The Psychology of Stupidity

Is it possible to conduct a scientific study of fools? That’s a provocative question! We’re aware of some absurd research (like “Can flatulence protect against fear?”) and studies on idiotic professions that have no social value or moral satisfaction. But what about studying fools themselves?

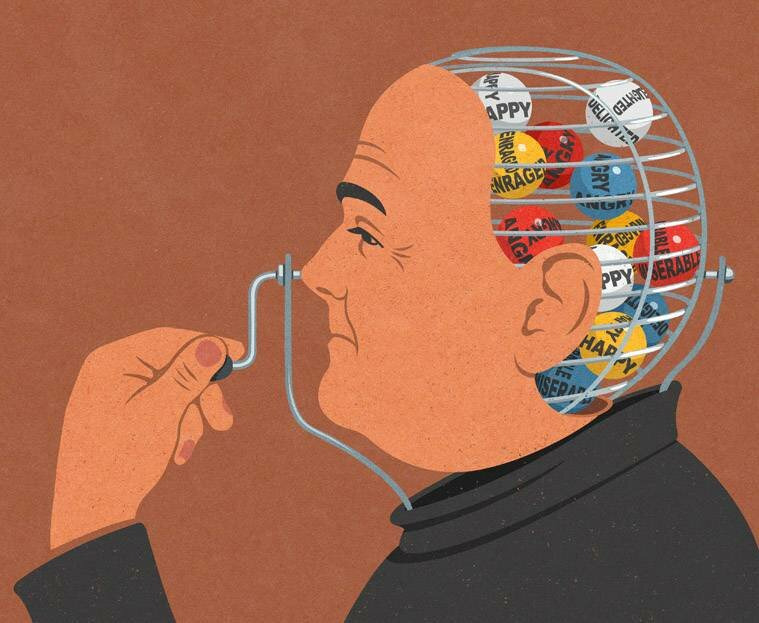

If you look at scientific psychological literature, it becomes clear that stupidity, in general, is fairly well studied. So, in that sense, yes, a scientific analysis of fools is possible. However, such research is based on existing studies about human behavior. A typical portrait of a fool can be drawn by selecting certain data from various works. This gives us a relatively accurate idea of a fool (annoying, dim-witted, poorly mannered, intellectually limited) and even some of their types, such as the vain fool or the rude jerk with a touch of toxic narcissism and a complete lack of empathy.

Stupidity and Lack of Attention

Psychological research that doesn’t specifically target fools as objects of study can still help us understand why people sometimes act foolishly. Studies of routine scenarios show that most of the time, people don’t analyze their surroundings very carefully before acting. In stereotypical situations, they rely on a set of automatic actions triggered by internal or external cues. That’s why, when you’re crying, there’s always a fool who comes up and says, “Hey, how are you?” It’s as silly as looking at your watch twice in a row.

When we want to know the time, we look at our watch automatically. This automatic action is useful because it doesn’t require much focus. However, as a result, we get distracted, think about something else, look without seeing, and don’t absorb the information—so we have to check the time again. Silly, isn’t it?

Attention resource studies have shown that we often don’t notice changes, even important ones. That’s why you might hear complaints like, “I lost 20 pounds on a diet, and that idiot didn’t even notice.” Research on the “illusion of control” explains why “there’s always some fool who keeps pressing an already-pressed elevator button.” And studies on social influence answer why, when one fool drives the wrong way down a one-way street, another fool follows, and when a third fool is asked on a game show what revolves around the Earth—the Moon or the Sun—he asks the audience for help.

It seems people often deviate from rational behavior and expected norms. The most foolish are those whose deviations are the most extreme. Such people usually have a simplified worldview: they struggle with large numbers, square roots, complexity, and the Gaussian curve—usually only noticing its lower ends. As Stalin once said, “The death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic.” We all prefer entertaining life stories over boring scientific reports. But the fool absolutely loves such stories. He’s even heard on the news that someone fell from the 40th floor and survived.

Stupidity and Beliefs

Research on beliefs has revealed the phenomenon of the “Belief in a Just World,” perhaps best illustrated by the foolish statement: “She was raped because she dressed too provocatively.” The more foolish a person is, the more they believe the victim deserved what happened. Fools also look down on those who can’t stand up for themselves.

A fool excels at believing in all sorts of nonsense: conspiracy theories, the Moon’s influence on human behavior, the benefits of homeopathy that “saved his dog”—what more proof do you need? On May 28, 2017, TV showed a motorcycle riding down the highway without a driver, who had fallen off earlier. Fools thought a ghost was driving, while smarter people attributed it to the gyroscopic effect. There seems to be an inverse relationship between mystical beliefs and the ability to win a Nobel Prize.

In the same area of beliefs, researchers found differences between “naive young fools” and “senile old fools.” It’s proven that negative memories fade over time, leaving only the good ones. So, the older we get, the more attractive the past seems, making old fools nostalgically claim, “Things were better back then.”

Researchers say our irrational behavior is driven by the need to control everything. Every living creature has this need (just watch how your dog rushes to the door every time the bell rings, even though no one’s coming for him). This need for control leads people to do absurd things, like visiting fortune-tellers. In France, about 100,000 people claim to be “psychics,” earning up to 3 billion euros a year. Even though researchers have found no evidence of psychic abilities, it doesn’t stop these frauds from getting rich. It’s estimated that about 20% of women and 10% of men have visited a psychic at least once. Most of these “psychics” have no regrets about their chosen path, and in the end, we get jerks profiting off fools. The need for control often leads to the illusion of control, and fools are the most likely to be deluded. For example, when someone is a passenger in a car, their fear of an accident increases. A fool can’t sleep as a passenger but sleeps just fine when driving.

A fool throws dice harder to get a “6” and picks certain numbers in the lottery. He loves stepping in dog poop but avoids walking under ladders because it’s bad luck. He reasons that he won the lottery only because he dreamed of the number “6” six nights in a row, and since 6 x 6 = 42, he picked “42” and won. In this sense, you could say a fool is mentally healthy, since this illusion is much weaker in people with depression.

Studies on Fools That Teach You About Work

In another area of research, fools use strategies to protect their self-esteem. Studies on the “false consensus effect” show that people tend to overestimate how many others share their flaws. For example, when a reckless driver is scolded for running a stop line, he replies, “Nobody stops here anyway!”

A fool often refers to the past. In the maternity ward, he says, “I knew it would be a boy”; watching TV, “I was sure Macron would become president”; to you, “I knew you’d say that!” Is he a psychic? No, he just uses “I knew it” strategically, mainly to appear more knowledgeable than he really is. Of course, don’t bother telling fools about these studies—they’ll just deny everything.

To maintain self-respect, many people overestimate their abilities. Psychological studies have shown that most people rate their intelligence above average. On one end of the scale are insecure simpletons, who are often seen as easy marks and get taken advantage of. On the other end are arrogant jerks with inflated egos. Such people can be costly to society if they get lost in the mountains or at sea, convinced they’re unbeatable athletes.

Finally, egocentrism helps distinguish a simple fool from an old-fashioned jerk who never admits mistakes. In his three failed marriages, he blames three “idiots” he was unlucky to meet. His business failed because his partners were incompetent. As a teen, he noticed his socks stank, not his feet. When fined for speeding, he decided he was just unlucky. Fools don’t realize that luck is just an explanation for probability.

Psychologists Dunning and Kruger couldn’t have published a paper titled “Studies on Fools That Teach You About Work”—it wouldn’t have passed peer review. Yet, that’s exactly what their research is about! They found that incompetent people tend to overestimate their competence. So, an idiot who’s never owned a dog will explain to you how to train yours. Dunning and Kruger explain this by saying that people with low skills often can’t accurately assess their abilities. But there’s more: according to them, if an incompetent person overestimates their competence, they also can’t recognize competence in others.

Thanks to this research, we understand why a foolish client tries to tell a professional how to do their job. Or why, when you lose something, there’s always a fool who asks, “Hey, where did you last see it?” And why an idiot confidently claims, “Being a lawyer is easy, you just need to know the laws,” “Quitting smoking? Easy, if you have willpower,” “Flying a plane? No harder than driving a bus.” After a quantum physics lecture he didn’t understand, the fool will look the lecturer in the eye and say, “Well, it all depends on the circumstances…”

Dunning and Kruger even suggest that if we were more modest, we wouldn’t vote, since we’re so incompetent in economics, geopolitics, government, and election programs—and have no idea how to improve the country. Yet, the fool will say in a café, “I know how to stop the crisis!”

Studies among Asian populations show the opposite of the Dunning-Kruger effect: a tendency to underestimate one’s abilities. In Eastern cultures, it’s not customary to show off or claim to know more than others.

The Stupidity Radar

Although there are many ways to spot stupidity, let’s end this overview with “cynical distrust,” which fools suffer from more than others. Cynicism is a set of negative beliefs about human nature and motivation. Fools often fall victim to sociopolitical cynicism—just start a conversation on the topic. Their thoughts are summed up in a few phrases without verbs: “It’s all corruption, extortion, and prostitution,” “All psychologists are frauds,” “Journalists are sellouts.” They believe people only avoid stealing out of fear of getting caught.

When you’re crying, there’s always some fool who comes up and asks, “Hey, how are you?”

A fool lives in a world of incompetence and scams. Studies show that cynical fools are so suspicious and closed off that they miss out on career opportunities and end up with lower incomes.

Overall, you could say that a fool combines the most extreme forms of various psychological tendencies identified by researchers. Whoever collects the full set is considered the King of Fools—the biggest fool the world has ever seen.

But perhaps more important than the question “Can fools be studied?” is “Why are there so many of them?” In fact, just shout “Hey, idiot!” on the street, and everyone turns around. And again, scientific literature gives us several answers.

First, we all have a kind of “stupidity radar”—a negative perception of the world. This means we pay more attention to and are more interested in negative events than positive ones. Negative perception heavily influences people’s opinions, prejudices, stereotypes, and superstitions. If an apartment is messy, we notice immediately, but we don’t focus on how clean it is after tidying up. Thanks to this negative perception, we spot fools around us much faster than geniuses. The same perception makes us look for someone to blame for our failures. If we’re looking for our house keys, we’re unlikely to admit we misplaced them ourselves—we’re sure someone else moved them: “Who touched my stuff again?!” And if our plan fails, we look for someone to blame, accusing some idiot who ruined everything.

Finally, researchers have identified the “fundamental attribution error”: we tend to explain other people’s actions and behavior by their personality traits rather than external circumstances. Most of the time, the conclusion is obvious—we’re dealing with a fool. So, when a car speeds past us, it’s because the driver is an idiot, not because his child was hurt at school. When a friend doesn’t reply to a message for two hours, it’s because he’s mad, not because his internet is down. If a coworker doesn’t return a folder, it’s because he’s lazy, not because he’s swamped with work. If a teacher gives a curt answer, it’s because he’s a jerk, not because the question was silly. This perception also increases our ability to see fools everywhere. These are at least two reasons why we’re so sensitive to stupidity.