Principles of Facial Expression Analysis in Brief Communication

Facial expression analysis, aimed at assessing a person’s reaction to external stimuli or evaluating the functioning of internal appraisal systems responsible for emotional responses, has become widespread thanks to available tools such as the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). These tools allow for objective description of facial expressions and, through various methods, interpretation of the collected data. Unfortunately, in certain situations—such as short-term communication (for example, during a job interview)—it is not always possible to use the standard FACS algorithm: (1) video recording, (2) describing facial expressions using FACS codes, (3) interpreting the obtained data. Nevertheless, interpreting facial reactions without specialized recording tools is possible, and the information gained can be significant for decision-making.

Facial reaction analysis in short-term communication is based on two principles: maximum objectivity in perceiving the face and the “stimulus–response” principle, where the interviewer evaluates the interviewee’s reaction to a given stimulus (a question or an artificially created situation).

Objectivity in Facial Perception

Objectivity in perceiving the face is impossible without understanding the basic psychological principles of facial perception. These include “perception biases” (attempts to link certain facial features with personality traits or behavioral tendencies) and the principle of adaptation to “habitual” facial expressions.

“Perception biases” originate both from the long-discredited field of physiognomy (an ancient system of assessing people by their faces) and from the objective influence of facial anatomy on our perception, particularly the width-to-height ratio of the face. The greater this ratio, the more masculine and trustworthy the face appears. This ratio is determined by testosterone exposure in the womb. Studies show that this ratio does not affect behavior or personality, only how others perceive the person. An interviewer may unconsciously trust someone with a higher width-to-height ratio more, not realizing this trust is based on facial anatomy, not reality. The same applies to facial dynamics—calmer facial expressions inspire more trust, while hyperkinetic expressions (where there is little or no connection between felt emotion and its facial display) can disorient the interviewer, distracting attention from both the face and other behavioral aspects.

Adaptation to certain facial expressions is a key principle of facial perception and can often lead to a loss of objectivity. A classic example is the lack of reaction from relatives to the sad expressions of depressed patients; relatives become so used to seeing this expression that it loses meaning. Another example is the lack of conscious reaction to expressions of contempt (a sign of dominance) in hierarchical or competitive work environments.

If adaptation to certain facial expressions is likely, it is recommended during conversation to temporarily shift focus from the face as a whole to specific anatomical markers, which helps quickly restore objectivity.

The “Stimulus–Response” Principle in Brief Communication

Using the “stimulus–response” principle in facial analysis during brief communication is necessary due to the low frequency of significant facial reactions and microexpressions during so-called neutral conversations, which pose no emotional risk to the interviewee.

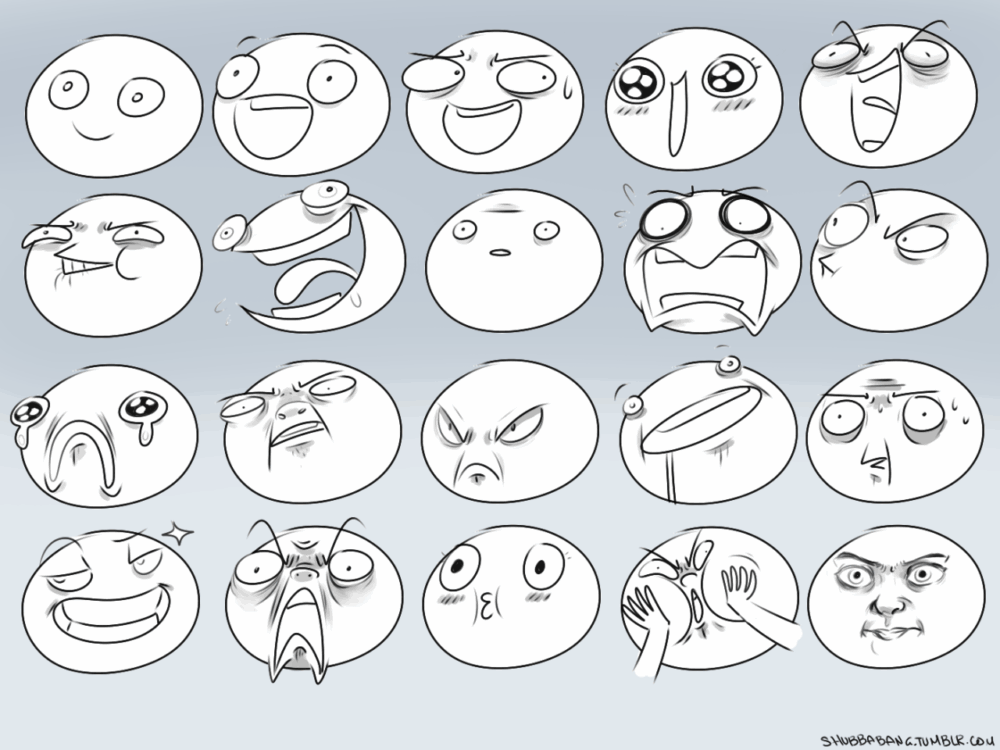

Unlike the classic FACS algorithm (video recording, coding, and interpretation), brief communication uses approaches focused on categorizing and evaluating behavior in real time. It is effective to combine two approaches to facial expression analysis: the discrete and the componential approaches.

The Discrete Approach

The main proponent of the discrete approach is renowned American psychologist Paul Ekman, who identified seven basic emotions, each with a specific facial expression and functional meaning. Ekman also introduced the concept of “microexpressions”—brief, involuntary facial expressions of genuine emotion. Because facial muscles have dual innervation, they can contract both voluntarily and involuntarily. The dynamics differ: automatic, unconscious contractions are symmetrical, smooth, and often faster. Microexpressions, lasting only 40 to 200 milliseconds, reveal true, deep emotions. Detecting microexpressions in real time without video recording requires special training, and their rarity (on average, in only 2% of studied communication acts) limits their use in brief communication. However, when provocative stimuli are used, the frequency of microexpressions increases.

This approach is highly convenient for brief communication and involves using provocative questions and statements, evaluating reactions based on discrete basic emotions and their microexpressions. It allows for fairly accurate verification of the truthfulness of statements.

The interviewee is presented with a series of provocative questions designed to elicit specific emotional reactions. For example, the interviewer tells the person they are believed to be innocent and that everything they said is trusted. An innocent person shows joy, even delight, while a guilty person, when their lie is believed, shows contempt, relief, or a smile mixed with contempt. Expressing disbelief to an innocent person provokes surprise and anger, while expressing disbelief to a liar provokes fear, fake surprise, and disgust.

| TRUTH | LIE | |

|---|---|---|

| BELIEVE | Joy (sensory surprise) | Contempt, Relief |

| DON’T BELIEVE | Surprise, Disagreement, Anger | Fear of exposure, Fake surprise, Disgust |

The Componential Approach

The second approach, effective in time-limited situations, is the componential approach to emotion and facial expression formation, proposed by Klaus Scherer in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Scherer’s approach is based on the sequential appraisal of events according to several criteria related to a person’s goals and needs, both conscious and mostly unconscious. The appraisal sequence includes four criteria:

- Event relevance: Does the event require attention, further consideration, or active response?

- Consequences: How will the event or its consequences affect quality of life and the achievement of immediate and long-term goals?

- Coping potential: The ability to manage or respond to the event.

- Consistency with moral and ethical norms: Does the event align with the person’s values?

Evaluating an event according to each of these criteria helps to understand the meaning of individual facial elements, which is not possible using only the discrete approach.

Conclusion

In summary, the principles of facial expression analysis require an integrative approach and the elimination of “perception biases” to maximize objectivity. This enables quick and effective real-time use of facial expression analysis techniques.