Post-Traumatic Growth: Finding Meaning and Creativity After Trauma

Psychologist and cognitive scientist Scott Barry Kaufman explores the concept of post-traumatic growth—how traumatic experiences that shake the very foundations of our sense of self can become the basis for a more meaningful life and self-expression. He also explains why trying to suppress painful thoughts, emotions, and feelings only strengthens our sense of helplessness, while acknowledging them helps us accept life’s inevitable paradoxes and develop a more nuanced perception of the world.

Kintsugi: The Art of Embracing Cracks

Kintsugi is a centuries-old Japanese art of repairing cracked pottery. Instead of hiding the cracks, this technique involves joining the broken pieces with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Once reassembled, the pottery is beautiful again, even with its visible fractures.

At this point in history, many people wonder if we can have a second life. When we “put ourselves back together,” can we recover with dignity? Science suggests that not only can we recover, but we can also demonstrate an incredible human capacity for resilience and growth.

From Resilience to Growth

In his landmark 2004 work, clinical psychologist George Bonanno advocated for expanding our understanding of how people respond to stress. He defined resilience as the ability of individuals who have experienced life-threatening or traumatic events to maintain a relatively stable, healthy level of psychological and physical functioning. Bonanno analyzed numerous studies showing that resilience is quite common, is not simply the absence of psychopathology, and can be achieved through multiple, sometimes unexpected, paths. Considering that about 61% of men and 51% of women in the U.S. report at least one traumatic event in their lives, human resilience is truly remarkable.

In fact, many people who experience trauma—such as being diagnosed with a chronic or incurable illness, losing a loved one, or suffering sexual assault—not only show incredible resilience but are also transformed by the experience. Research shows that most trauma survivors do not develop PTSD, and many even report psychological growth after their ordeal. Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun coined the term “post-traumatic growth” to describe this phenomenon, defining it as positive psychological change resulting from the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances.

According to research, adversity can foster growth in seven key areas:

- Greater understanding of life

- Stronger appreciation and strengthening of close relationships

- Increased compassion and altruism

- Discovery of new opportunities or life purpose

- Deeper awareness and use of personal strengths

- Enhanced spiritual development

- Creative growth

Of course, most people who experience post-traumatic growth would have preferred to avoid the trauma altogether, and only in a few of these areas does growth exceed that from positive life experiences. Still, most people who go through post-traumatic growth are often surprised by the transformational changes that occur—often unexpectedly—as they try to make sense of the incomprehensible event.

Rabbi Harold Kushner expressed this well when reflecting on the death of his son:

“Because of Aaron’s life and death, I became a more sensitive person, a more effective pastor, a more responsive counselor. None of this would have happened without that experience. And I would give up all those achievements in a second if I could have my son back. If I could choose, I would give up all the spiritual growth and depth that came to me through our experience… But I cannot choose.”

There’s no doubt that trauma shakes our world and forces us to reconsider our goals and dreams. Tedeschi and Calhoun use the metaphor of an earthquake: we usually rely on a certain set of beliefs and assumptions about the world’s benevolence and manageability, but traumatic events tend to shatter this worldview, knocking us out of our usual perspectives and forcing us to rebuild ourselves and our world.

But what choice do we have? As Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl said:

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

In recent years, psychologists have begun to understand the psychological processes that turn adversity into advantage, and it’s becoming clear that this “seismic psychological restructuring” is actually necessary for growth. It’s precisely when the core structure of the self is shaken that we are best positioned to seek new opportunities in our lives.

Polish psychiatrist Kazimierz Dąbrowski also argued that “positive disintegration” can be a growth-promoting experience. After studying people with high levels of psychological development, Dąbrowski concluded that healthy personality development often requires the disintegration of its structure, which can temporarily lead to psychological tension, self-doubt, anxiety, and depression. However, Dąbrowski believed this process can also lead to deeper exploration of who a person can become, ultimately resulting in a higher level of development.

Exploring Thoughts and Feelings

The key factor that allows us to turn adversity into advantage is how fully we explore our thoughts and feelings related to the event. Cognitive exploration—defined as a general interest in information and a tendency toward flexibility and openness in processing it—allows us to approach unsettling situations with curiosity, increasing the likelihood that we’ll find new meaning in what seems incomprehensible.

Of course, many steps toward growth after trauma go against our natural tendency to avoid extremely unpleasant emotions and thoughts. But only by letting go of our natural defense mechanisms and facing unpleasant feelings head-on—viewing everything as fertile ground for growth—can we begin to accept life’s inevitable paradoxes and develop a more nuanced view of reality.

After a traumatic event, whether it’s a serious illness or the loss of a loved one, it’s natural to ruminate, to think constantly about what happened, replaying the same thoughts and feelings over and over. Rumination is often a sign that you’re struggling to make sense of what happened, actively breaking down old belief systems and building new structures of meaning and identity.

While rumination usually starts as automatic, obsessive, and repetitive, over time this reflection becomes more organized, controlled, and purposeful. This transformation process can be painful, but rumination—combined with a strong social support system and other forms of self-expression—can be beneficial for growth, allowing us to tap into deep sources of strength and compassion we never knew we had.

Similarly, emotions like sadness, grief, anger, and anxiety are common reactions to trauma. Trying to suppress or “self-regulate” these emotions, or avoiding experiences—thoughts, feelings, and sensations that cause fear—paradoxically makes things worse, reinforcing our belief that the world is unsafe and making it harder to achieve valuable long-term goals. By avoiding experiences, we shut down our exploratory abilities, missing out on many opportunities for positive experiences and meaning. This is a central theme of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which helps people increase their “psychological flexibility.” By developing psychological flexibility, we approach the world with curiosity and openness and respond to events in line with our chosen values.

Consider a study by Todd Kashdan and Jennifer Kane, which examined the role of experiential avoidance in post-traumatic growth among college students. The most commonly reported traumas in this group included the sudden death of a loved one, car accidents, domestic violence, and natural disasters. Kashdan and Kane found that the greater the distress, the more pronounced the post-traumatic growth—but only among those with low levels of experiential avoidance. Those who reported higher distress and lower avoidance showed the highest levels of growth and sense of life’s meaning.

For those who avoided experiences, the results were the opposite: greater distress was associated with lower post-traumatic growth and less sense of meaning. This study adds to a growing body of literature showing that people with low anxiety and low experiential avoidance (i.e., high psychological flexibility) report higher quality of life. But it also shows that people who experience post-traumatic growth are able to find more meaning in life.

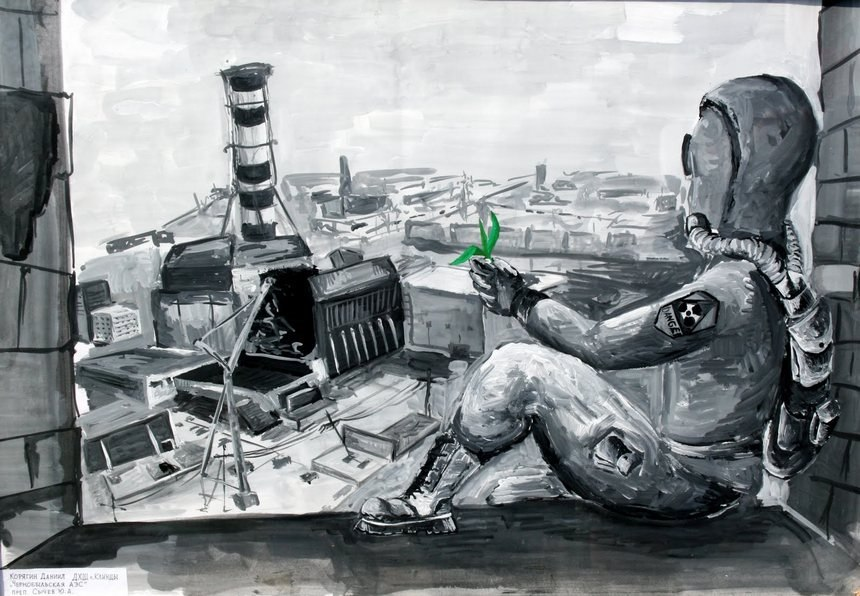

Finding meaning can be fertile ground for creative self-expression.

Creativity After Trauma

The link between adversity and creativity has a long and distinguished history, and now scientists are beginning to uncover the mysteries behind this connection. Clinical psychologist Marie Forgeard asked people to describe the most stressful events in their lives and indicate which circumstances had the greatest impact on them. The list of adverse events included natural disasters, illnesses, accidents, and assaults.

Forgeard found that the form of cognitive processing was crucial in explaining post-traumatic growth. Obsessive forms of rumination led to decreases in several areas of growth, while deliberate reflection led to increases in five areas of post-traumatic growth. Two of these areas—positive changes in relationships and increased perception of new opportunities in life—were linked to greater creative growth.

In her book When Walls Become Doorways: Creativity and the Transforming Illness, Tobi Zausner analyzed the biographies of outstanding artists who suffered from physical illnesses. Zausner concluded that such illnesses created new opportunities for their creativity by breaking old habits, disrupting equilibrium, and forcing artists to generate alternative strategies to achieve their creative goals.

Taken together, research and personal stories confirm the potentially enormous benefits of art therapy or expressive writing in facilitating recovery after trauma. Studies have shown that writing about emotionally charged topics for just fifteen to twenty minutes a day helps people find meaning in difficult experiences and better express both positive and negative emotions.