Only Two Choices

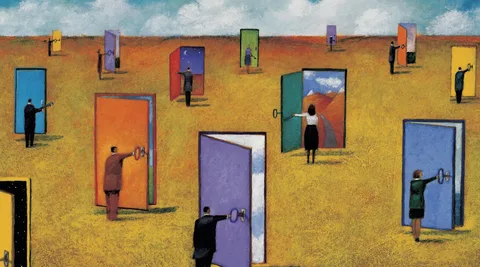

The well-known existential psychologist S. Maddi notes that whenever we are faced with the need to make a choice, we should remember that, in reality, there are always only two options before us.

- A choice in favor of the past

- Or a choice in favor of the future

Choosing the Past

This is the choice of the familiar and the known—what has already been in our lives. By choosing the past, we choose stability and well-trodden paths, maintaining the confidence that tomorrow will be much like today. No changes or effort are required. All the peaks have already been reached, and we can rest on our laurels. Or, perhaps, things are bad and difficult, but at least it’s familiar. And who knows, maybe the future could be even worse…

Choosing the Future

Choosing the future means choosing anxiety, uncertainty, and unpredictability. The real future cannot be predicted. While we can plan for the future, often this planning is just a way to endlessly repeat the present. The true future is unknown, and this choice robs us of peace, planting worry in our hearts. But growth and development are only found in the future. The past is already gone and can only repeat itself; it will never be different.

So, every time we face a serious (or even not-so-serious) decision, we are met by two angels: one named Calm, the other Anxiety. Calm points to the well-trodden road, while Anxiety points to a path leading into the unknown. The first road leads backward, the second—forward.

The Story of Abraham

As the old Jewish man Abraham was dying, he called his children to him and said:

When I die and stand before the Lord, He will not ask me, “Abraham, why weren’t you Moses?” Nor will He ask, “Abraham, why weren’t you Daniel?” He will ask me, “Abraham, why weren’t you Abraham?!”

How to Make the Right Choice?

If, as already mentioned, the real future cannot be predicted, how can we know if our choice is right?

This is one of the small tragedies of life: the correctness of a choice is determined only by its result—which lies in the future. And the future doesn’t exist yet… Realizing this, people often try to program the result, to play it safe. “I’ll do it when it’s absolutely clear… When there’s a definite alternative…”—and often, the decision is postponed forever. Because no one has ever made a decision tomorrow. “Tomorrow,” “later,” and “someday” never come. Decisions are made today, here and now, and begin to be realized at that very moment. Not tomorrow, but now.

The Price of Choice

The weight of a choice is also determined by the price we must pay to make it happen. The price is what we are willing to sacrifice for our choice to become reality.

A choice without a willingness to pay the price is impulsiveness and a readiness to play the victim. The victim makes decisions, but when it’s time to pay the price, starts to complain and look for someone to blame. “I feel bad, I feel hurt”—these are not the words of a victim, just statements of fact. “If I had known it would be this hard…”—that’s where victimhood can begin, when we realize we didn’t consider the cost. One of life’s most important questions is, “Is it worth it?” The price of altruism is forgetting oneself. The price of egoism is loneliness. The price of always trying to please everyone is often illness and anger at oneself.

Once we understand the price of our choice, we can change it—or leave things as they are, but without complaining about the consequences and taking full responsibility.

Responsibility

Responsibility is the willingness to accept that you are the cause of what has happened—to you or to someone else (according to D.A. Leontiev). It’s the recognition that you are the reason for the events taking place. What exists now is the result of your free choice.

Every “Yes” Means a “No”

One of the hardest consequences of choice is that every “yes” always means a “no” to something else. By choosing one alternative, we close off another. We sacrifice some opportunities for others. The more options we have, the harder it is. Sometimes, the presence of alternatives tears us apart: “Should” and “want.” “Want” and “want.” “Should” and “should.” To resolve this conflict, we may resort to three tricks:

- Trying to pursue two alternatives at once.Chasing two rabbits at once. We all know how that ends—you catch neither. Because, in reality, no choice has been made, and you remain where you started. Both alternatives suffer as a result.

- Making a half-choice.Deciding and taking some actions, but constantly returning in your mind to the point of choice. “What if the other alternative was better?” I often see this in my students. They decide to come to class (because they have to), but their minds are elsewhere. As a result, they’re not really present in class—only their bodies are. And they’re not where they want to be either—only their thoughts are. So, at that moment, they don’t exist at all. They are dead to life here and now. To choose halfway is to die to reality. If you’ve made a choice, close off the other alternatives and immerse yourself in your decision.

- Waiting for things to resolve themselves.Not making any decision, hoping that one of the alternatives will disappear on its own, or that someone else will make the choice for you. There’s a comforting saying for this: “Everything happens for the best.” Not “everything I do,” but “everything that happens”—meaning it happens by itself or by someone else, but not by me. Another magic mantra: “Everything will be fine…” It’s nice to hear from a loved one in a tough moment, and that’s understandable. But sometimes we whisper it to ourselves, avoiding a decision because we’re afraid: what if the decision is rushed? Maybe we should wait a little longer? At least until tomorrow (which, as we know, never comes)… When we wait for things to resolve themselves, we might be right. But more often, things resolve themselves, just not the way we would have liked.

Maximizers and Satisficers

There are also maximizers and satisficers, as Barry Schwartz describes in his book “The Paradox of Choice.” Maximizers strive to make the best possible choice—not just to minimize error, but to pick the very best alternative available. If they’re buying a phone, it has to be the best in terms of price-quality ratio, or the most expensive, or the newest and most advanced. The main thing is that it’s “the best.”

In contrast, satisficers aim to choose the option that best meets their needs. The phone doesn’t have to be “the best”—it just needs to make calls and send texts, and that’s enough. Maximizing complicates choice, because there’s always the chance that something better is out there, and this thought gives maximizers no peace.

The Cost of Not Choosing

Making choices can be hard, but refusing to make a decision leads to even heavier consequences. This is called existential guilt—the guilt before oneself for missed opportunities in the past.

Regret for lost time… The pain of unspoken words, of unexpressed feelings, which arises when it’s already too late… Unborn children… The job not taken… The chance not used…

The pain when it’s no longer possible to turn back. Existential guilt is the feeling of betraying oneself. And we can hide from this pain, too—by loudly declaring that we never regret anything, that we leave the past behind without doubt or looking back. But that’s an illusion.

We can’t detach and throw away our past. We can ignore it, suppress it, pretend it’s not there—but we can’t get rid of it, except at the cost of forgetting who we are. Wherever we go, we drag the cart of our past experience with us. “It’s silly to regret what’s already happened.” No, it’s not silly to regret… What’s silly, perhaps, is to ignore the fact that we once made a mistake, and to ignore the feelings that come with it. We are human. We don’t know how to throw away pain.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Making a Serious Life Choice

- Is my choice in favor of the past or the future?

- What is the price of my choice (what am I willing to sacrifice to make it happen)?

- Is my choice driven by maximizing or satisficing?

- Am I ready to take full responsibility for the consequences?

- After choosing, do I close off all other alternatives?

- Am I making the choice fully, or only halfway?

- And finally, the question of meaning: “Why am I choosing this?”