Mass Psychology: The Power of the Subconscious

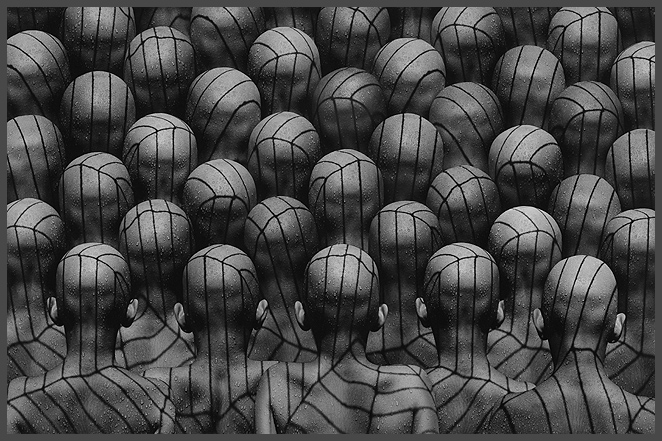

Part 1. Historical Background: Principles and Methods

One thing is certain and important: the subconscious, or the unconscious, plays the main role in our psyche. This is where our thoughts, desires, actions, and aspirations are born, which later shape human behavior. The behavior of the individual—who is, in turn, a tiny particle of the vast mechanism called the masses, the crowd, or mass formation.

Methods of influencing the masses have been studied for a long time. Even in ancient times, certain principles were developed, some of which have survived almost unchanged, while others have evolved or been lost over time. Brilliant minds throughout history have been fascinated by the mechanisms of influencing crowds and the subconscious of the masses. These principles were developed both by scientists (like Professor Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis) and intuitively discovered by practitioners—such as dictators like Hitler and Stalin, political leaders, preachers, and even famous writers and poets who could gather crowds of admirers in the early 20th century, even in a largely backward and uneducated country without modern technology like TV or the internet.

Yet, the masses easily obeyed those individuals who understood and shaped the laws of mass formation. What are these main principles?

1. The Effect of Submitting the Individual “I” to the Collective

As Gustave Le Bon wrote: “…the individual feels an overwhelming sense of power, allowing him to give in to primal urges that he would restrain when alone.” In other words, when a person is in a crowd, they can be “themselves,” giving free rein to ancient instincts that are suppressed in civilized society. Culture leaves an invisible mark on individual behavior. While deep down we might want to act on primitive instincts, modern society forces us to restrain them. For example, cannibalism is unthinkable today, though in extreme situations (like the GULAG or the Siege of Leningrad), it has occurred. These instincts remain in our unconscious, surfacing in expressions like “my sweet” or “I could just eat you up.”

2. The Contagion Effect

Le Bon described contagion as a phenomenon akin to hypnosis: “Every action and feeling is contagious in a crowd, to such a degree that the individual easily sacrifices personal interest for the collective.” This is also tied to culture and civilization. Society imposes norms and laws, and breaking them brings punishment. But in a crowd, the individual becomes depersonalized. If someone acts against social norms, the crowd punishes them. However, if another person repeats the act and it goes unpunished, others follow, hypnotized by the example. In a crowd, it’s easier to riot, loot, or commit violence—responsibility is diffused. What’s possible for a crowd is nearly impossible alone. The individual feels the immense power of the crowd, as seen in wartime heroism or riots.

3. Suggestibility

Le Bon noted that individuals in an active mass soon fall under a state close to “enchantment,” losing conscious personality and will, with all thoughts and feelings oriented by the crowd. Under suggestion, people act with irresistible impulse. This is even stronger in crowds than in hypnotized individuals, as the suggestion is amplified by interaction. Vladimir Bekhterev wrote that individuals in a crowd infect each other, becoming agitated by noble or base impulses. Rarely does a crime occur without direct or indirect influence from others, often acting as suggestion. Sometimes, just a word or example is enough to push someone to action.

We see this in audiences where paid “plants” laugh or clap, prompting others to follow. Or when someone throws the “first stone” in a crowd, and others join in, leading to riots or attacks. Suggestion also explains heroic acts and self-sacrifice in war, when a leader’s word inspires troops to impossible feats. Suggestion can override reason and will, leading to both great deeds and terrible crimes. Crowds can be easily swayed to noble or brutal acts, depending on what is stirred within them.

Freud wrote: “The mass is impulsive, changeable, and excitable; it is almost entirely led by the unconscious. Its impulses can be noble or cruel, heroic or cowardly… The mass cannot tolerate delay between desire and fulfillment. It feels omnipotent, and the individual loses the sense of the impossible. The mass is credulous and easily influenced, uncritical, and thinks in images. Its feelings are simple and exaggerated. It knows neither doubt nor uncertainty. The mass quickly reaches extremes; suspicion becomes certainty, a seed of dislike becomes wild hatred. To influence it, one need not use logical arguments, but vivid images, exaggeration, and repetition. The mass respects strength and demands it from its hero, even violence. The mass falls under the magical power of words.”

History shows that crowds are often led not by mere leaders, but by fanatics—like Hitler, who led millions of Germans into a global catastrophe, or Lenin and Stalin, who used terror and repression to control the masses. These principles of mass psychology, described by Le Bon and Freud, have been used throughout history and are even more effective today thanks to modern technology, which allows a single leader to influence millions.

Part 2. Modern Methods of Influencing the Subconscious to Control the Masses

The means and methods of influencing the subconscious have changed dramatically over the past century. With the rise of television, the internet, and print media, it has become much easier to reach large audiences. For example, after 20-25 minutes of watching TV, the brain begins to absorb any information presented. This is the basis of TV advertising, which relies on suggestion. Even if we initially reject an ad, repeated exposure embeds it in our subconscious. Later, when choosing a product, we instinctively prefer the one we’ve “heard of,” associating it with something familiar or positive. The longer the exposure, the stronger the effect.

Manipulation of mass consciousness is most effective when people are under constant information exposure. In such cases, people don’t need to think for themselves—everything is “thought out” for them, forming a new ideology. This is easier if the individual is removed from their usual environment (e.g., army, prison, orphanage, boarding school), where established norms and rules prevail. The newcomer quickly adapts to these rules, forming new values and forgetting their old way of life. Over time, they become ready to submit and may even forget who they really are, as they now follow new rules that have become “familiar.”

Initially, the psyche resists. Someone abruptly removed from their environment (e.g., drafted into the army or arrested) experiences rejection and discomfort. But eventually, they break down and unconsciously accept the new conditions. The specifics of the new environment, such as language or jargon, also play a role. Jargon is common in criminal circles, the military, and professional communities. Learning the new language helps the individual integrate and stop being a newcomer, which is psychologically important.

In a new environment, not only do values shift, but new “parental figures” emerge—commanders, supervisors, or leaders—who dictate daily life and discipline. The individual unconsciously submits, and if they resist, they are “broken.” The success of manipulation also depends on the emergence of new values, replacing the old ones. Religious cults and the establishment of Soviet power are examples where all principles of mass manipulation were used, resulting in profound changes in collective consciousness.

Modern mass influence combines advertising and mass communication. Advertising often replaces genuine values with imposed ones, making people feel they no longer belong to themselves. Even if they consciously resist, subconsciously they accept these new norms. This can also create inferiority complexes in those unable to afford certain products or lifestyles, driving some toward crime or easy money. The state, by promoting the idea that poverty is shameful, indirectly encourages such behavior.

Another technique is information fragmentation, which increases suggestibility. For example, the front page of a newspaper or the first minutes of a news broadcast present a summary of main events, preparing the audience. Fragmenting information across different sections prevents individuals from connecting the dots and understanding the full picture. Sensationalism and rapid-fire news stories scatter attention, lowering psychological defenses and critical thinking, making people more susceptible to suggestion. Timely advertising then penetrates the subconscious. Even if people don’t immediately act, when the time comes, they will be guided by what’s already in their subconscious.

What’s in our subconscious? Everything we’ve ever seen or heard. Aside from so-called phylogenetic memory (or the collective unconscious), everything we experience is stored in our subconscious, with few exceptions due to psychological defenses like repression.

There’s no other way.

Main Principles of Mass Manipulation

The main mechanisms are suggestion, contagion, and imitation. There are also six key principles of manipulation:

- Consistency Principle: People naturally want to be consistent. If someone is made to take a first step (like filling out a form or writing a positive review), they are likely to take the next step, becoming a “new client.”

- Authority Principle: We are more likely to comply with requests from people with authority or recognition (e.g., an academic, general, or governor) than from strangers.

- Liking Principle: We are more likely to trust and help attractive people. For example, we’re more likely to help a glamorous actress than a dirty, drunken beggar—this happens unconsciously.

- Reciprocity Principle: Also known as the “rule of gratitude.” Supermarkets use this by offering free samples, making us feel obliged to buy the product.

- Social Proof Principle: If many people buy a product, we unconsciously want to do the same. This explains the popularity of ratings, applause in audiences, and following the crowd.

- Scarcity Principle: People are motivated to buy when they fear missing out. In the Soviet era, books were scarce, and people bought them just because they were available. Now, with books widely available, print runs are much smaller. This demonstrates the power of scarcity in manipulating mass consciousness.

Unfortunately, most of us are susceptible to these manipulations.

References:

- G. Le Bon. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind.

- V. M. Bekhterev. Suggestion and the Crowd.

- Freud, S. Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. In: Psychoanalytic Studies. Minsk: Popurri, 2003.

- S. G. Kara-Murza. Manipulation of Consciousness.

Author: Sergey Zelinsky