Learned Helplessness Isn’t Really Learned: What Science Reveals

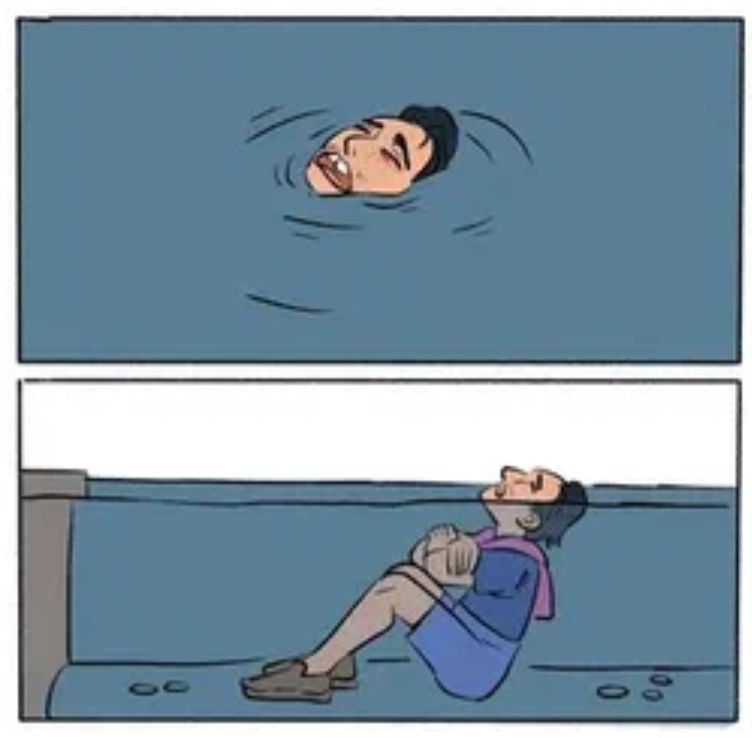

Learned helplessness isn’t actually learned at all. Martin Seligman wrote a detailed article on this for the 50th anniversary of his first experiments—the famous ones where dogs were subjected to electric shocks at irregular intervals for 24 hours. Later, when the cage was opened, the dogs didn’t try to escape the shocks; they just lay there and whimpered.

Later, Seligman and Maier revisited their own results. They identified two types of helplessness: objective and subjective. The dividing line between them is the factor of uncontrollability—the presence of external circumstances that occur regardless of our actions. An example of objective helplessness is a passenger’s reaction to severe turbulence on an airplane; in reality, all passengers can do is wait it out and follow the pilot’s instructions.

Subjective helplessness, unlike objective helplessness, is a purely cognitive phenomenon based on the expectation that factors outside our control will remain that way in the future. On a cognitive level, this takes the form of beliefs like “There’s no point in trying,” “I can’t influence anything anyway,” or “Nothing depends on me.” People often project these beliefs onto various areas of life, from career and self-fulfillment to civic engagement—whether it’s trying to influence local development or participating in parliamentary elections.

For 50 years, scientists have conducted various experiments with both animals and humans to understand why, in some situations, people look for ways to influence stressors, while in others, they give up. So, what did Seligman and Maier conclude?

Passivity in response to a recurring stressor isn’t learned at all. It’s a biologically default response to prolonged, uncontrollable negative events. This response is mediated by serotonergic activity in nuclei located in the reticular formation—the oldest part of the brain, much older than the cortex. This same structure is responsible, for example, for the orienting reflex—when you hear a loud, sudden noise and instinctively turn your head.

“What’s learned is cortical,” Seligman summarizes. “Learning is handled by the cortex, and that’s the secret to overcoming helplessness.” Thus, what’s actually learned is the response of overcoming repeated stress: seeking solutions, gaining control over stressors, or fighting back against painful stimuli.

A series of experiments with dogs, and later with people, confirmed this. In groups where participants initially had the opportunity to experiment and limit negative stressors, they learned to overcome helplessness the fastest. In groups where helplessness was initially objective, automatic learning didn’t occur, but active training led to positive results.

From a neurobiological perspective, activation of the medial prefrontal cortex automatically blocked the nuclei of the reticular formation—in other words, consciously learning to control a stressor literally switched off paralyzing helplessness.

Seligman emphasizes the need to develop models of proactive behavior—no one needs to be taught helplessness, he writes, but people do need to be taught proactivity, assertiveness, and standing up for their rights. He also highlights the importance of focusing on the future—instead of analyzing the past and present—and even criticizes cognitive-behavioral therapy for being too concerned with analyzing already-formed beliefs and behavioral patterns, when more attention should be paid to learning new beliefs and patterns.

“Hope is the habit of expecting that future bad events are temporary, local, and controllable, instead of seeing them as endless, global, and uncontrollable.” Seligman is convinced that healthy optimism isn’t innate; it must be learned.