How to Learn to Recognize Emotions

Paul Ekman discovered that, in terms of facial expressions, people from all cultures express emotions in the same way. He also identified micro-expressions—brief episodes of facial activity that reveal emotions, even when someone tries to hide them.

For a long time, science paid little attention to facial expressions. Charles Darwin was the first to study them, publishing his book “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals” in 1872. Darwin argued that facial expressions are universal not only for humans but also for animals: for example, both people and dogs bare their teeth when angry. However, Darwin believed that gestures, unlike facial expressions, are conventional and depend on cultural background.

For nearly a century, Darwin’s work was largely forgotten or only mentioned to be disputed. In the 1930s, French neuroanatomist Duchenne de Boulogne revisited it, attempting to disprove a Nazi scientist’s theory that “inferior races” could be identified by their gestures.

In the 1960s, American psychologist Paul Ekman popularized the hypotheses from Darwin’s book and Duchenne’s work. Ekman conducted studies to test these theories and found that Darwin was right: gestures do vary across cultures, but facial expressions do not. Critics argued that Hollywood and television had spread a standardized model of facial expressions worldwide. To challenge this, Ekman studied the facial expressions of a tribe in Papua New Guinea in 1967 and 1968. These people had no significant contact with Western or Eastern cultures and were at a Stone Age level of development. Ekman found that even in this case, the main emotions were expressed in the same ways as everywhere else.

The “Facial Action Coding System” (FACS)—a method for classifying human facial expressions, originally developed by Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen in 1978 and based on a collection of photographs with corresponding emotions—proved to be universal. This system, like sheet music for the face, allows us to determine which facial movements make up a particular emotional expression.

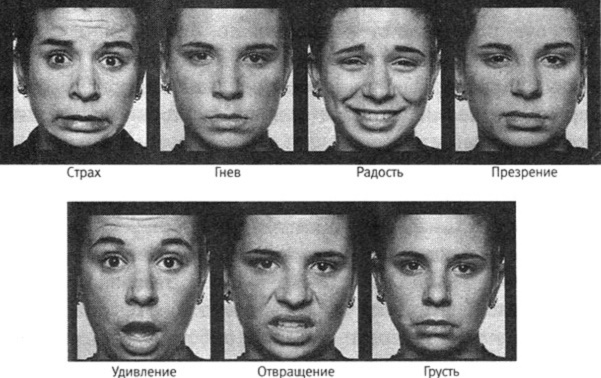

From Surprise to Contempt: The Seven Universal Emotions

There are only seven emotions that have a universal form of expression:

- Surprise

- Fear

- Disgust

- Anger

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Contempt

All of these are encoded in FACS and EmFACS (an updated and expanded version of the system), so each emotion can be identified by its characteristic features, including its intensity and degree of blending with other feelings. There are main codes (for example, code 12: “Lip Corner Puller,” the zygomatic major muscle), head movement codes, eye movement codes, visibility codes (such as code 70 when eyebrows are not visible), and general behavior codes to record actions like swallowing, shoulder shrugging, trembling, and more.

“There are uncontrollable, involuntary facial expressions, as well as softened or fake expressions, where the experienced emotion is weakened or a non-felt emotion is simulated,” writes Paul Ekman in his book “Telling Lies.” Involuntary expressions always show through the “mask” created on the face. These can be detected through micro-expressions, which usually last only fractions of a second, so training is needed to spot them.

There are three areas of the face that can move independently:

- Eyebrows and forehead

- Eyes, eyelids, and bridge of the nose

- Lower face: cheeks, mouth, most of the nose, and chin

Each area has its own movement pattern for each of the seven emotions. For example, with surprise, the eyebrows are raised, eyes are wide open, jaws drop, and lips part. Fear looks different: eyebrows are raised and drawn together, upper eyelids are raised exposing the sclera, lower eyelids are tense, the mouth is slightly open, and the lips are tense and pulled back.

In his book, Paul Ekman provides a detailed map of micro-movements for each universal emotion and offers photographs for self-practice. To quickly learn to identify emotions on faces, you need a partner to show you these photos—either fully or partially covered with an L-shaped mask. The book also helps you learn to determine the intensity of emotions and recognize components of mixed facial expressions, such as bittersweet sadness or startled surprise.

Deceptive Expressions: Message Control

“It’s easier to fake words than facial expressions,” writes Paul Ekman. “We’ve all been taught to speak, we have a large vocabulary and knowledge of grammar. There are not only spelling but also encyclopedic dictionaries. You can write your speech in advance. But try to do the same with your facial expressions. There’s no ‘dictionary of facial expressions’ at your disposal. It’s much easier to suppress what you say than what you show.”

According to Ekman, a person who lies with their facial expressions or words usually tries to satisfy a current need: a pickpocket feigns surprise, an unfaithful husband hides a smile of joy when seeing his lover if his wife is nearby, and so on. “However, the word ‘lie’ doesn’t always accurately describe what’s happening in these cases,” Ekman explains. “It implies that the only important message is the true feeling behind the false message. But the false message can also be important if you know it’s false. Instead of calling this process lying, it’s better to call it message control, because the lie itself can also convey useful information.”

In such cases, there are two messages on a person’s face: one reflects the actual feeling, and the other is what they want to convey. Ekman first became interested in this problem when he observed patients with severe depression. In conversations with doctors, they claimed (both facially and verbally) to feel joy, but in reality, they wanted to be discharged and commit suicide. In the TV series “Lie to Me,” the writers also address this issue: the mother of Dr. Cal Lightman commits suicide after deceiving psychiatrists in this way. Later, reviewing video recordings of her conversations with doctors, the main character discovers a micro-expression of sadness on her face.

Message control can take different forms:

- Attenuation

- Modulation

- Falsification

Attenuation usually involves adding facial or verbal comments to an existing expression. For example, if an adult is afraid of the dentist, they might wrinkle their face slightly, adding an element of self-disgust to their expression of fear. Through attenuation, people often signal that they can manage their feelings and behave according to cultural norms or the situation.

With modulation, a person adjusts the intensity of the emotion’s expression rather than commenting on it. “There are three ways to modulate facial expressions,” writes Ekman. “You can change the number of facial areas involved, the duration of the expression, or the amplitude of muscle contractions.” Usually, all three methods are used. In falsification, the facial process becomes false: the face shows an emotion not actually felt (simulation), shows nothing when a feeling is present (neutralization), or hides one expression behind another (masking).

The Physiology of Lying: Location, Timing, and Micro-Expressions

To learn to recognize lies on faces, pay attention to five aspects:

- Facial morphology (the specific configuration of features)

- Temporal characteristics of the emotion (how quickly it appears and how long it lasts)

- Location of the emotion on the face

- Micro-expressions (they interrupt the main expression)

- Social context (if you see fear on an angry face, consider whether there’s an objective reason for it)

People who control their facial expressions focus most on the lower part of the face: mouth, nose, chin, and cheeks. After all, we use the mouth for vocal communication, including nonverbal sounds like screams, crying, and laughter. However, eyelids and eyebrows more often reveal true feelings—though eyebrows can also be used for facial falsification, which can affect the appearance of the upper eyelids. What appears “out of place” during deception depends on what is being shown and what is being hidden. For example, expressing joy doesn’t require using the forehead—so if joy is masking another emotion, look for the hidden feeling in that area.

Ekman’s books can teach you to recognize various falsified facial expressions in different situations: spotting fearful eyebrows on a neutral face (indicating genuine fear), noticing the lack of tension in the lower eyelids on an angry face (suggesting fake anger), detecting leaks of true anger beneath a mask of disgust, observing pauses between verbal statements about an emotion and the appearance of its false version on the face (1.5 seconds), and paying attention to other important details.

But the main skill Ekman’s books and trainings develop is recognizing micro-expressions. These emotional displays usually last only a short time: from half to a quarter of a second. You can learn to spot them using the same photographs and L-shaped mask—if the images are shown in quick succession. The presence of micro-expressions does not necessarily mean a person is not masking, attenuating, or neutralizing their emotions. These brief episodes of facial activity are a symptom of deception or, at the very least, a sign that the person doesn’t know what they’re feeling. However, their absence doesn’t mean anything definitive.

Today, Paul Ekman and his research team conduct emotion recognition trainings for customs officers, police, border guards, HR professionals, and others who often need to detect deception or confirm facts. However, his methods are useful not only at the border: they can help journalists during interviews, teachers in the classroom, businesspeople in negotiations, and many others. Still, neither Dr. Lightman’s techniques from the TV series nor Dr. Ekman’s real-life methods, which inspired “Lie to Me,” should be used at home. Not every deception actually leads to negative consequences—and loved ones deserve the right to privacy, since not everything they hide concerns us.