What Is Congruence?

There’s a story about Virginia Satir. Already world-famous, she traveled the country giving lectures. At one university, the hall was packed—everyone eagerly awaited her appearance. Suddenly, a small, hunched-over elderly woman walked out and began to speak in a dull, monotonous voice: “Today we’ll talk about strong feelings like happiness, love…” The audience, having paid thousands of dollars for a three-day seminar, was bewildered. Then, Virginia stepped aside, straightened up, and, pointing to where she had just stood, said in a normal, emotional voice: “What you just saw is called incongruence. When posture, gestures, and facial expressions don’t match the content of speech, this mismatch causes strong rejection. The most important skill of any successful person is to be congruent! And that’s why we’re starting our seminar with this topic!”

There are several versions of this story, so don’t be surprised if you’ve heard it told differently.

Let’s talk about congruence. You might already know this term from geometry, where “congruence” refers to the similarity of shapes and is denoted by an equal sign with a wavy line above it (≅).

In psychology, the term “congruence” was introduced by Carl Rogers, one of the founders of humanistic psychology, and it entered NLP (Neuro-Linguistic Programming) through Virginia Satir.

Why Is Congruence Important?

People are complex beings and often want completely different things at the same time:

- I want that pastry, but it’s bad for my weight.

- I should work, but I don’t feel like it.

- I need to get up, but I want to sleep.

- I love him, but he’s so unsettled.

- He’s an idiot, but I can’t say that to his face.

- On one hand, “yes,” but on the other, “no.”

One of the most common conflicts is between “want” (the desire for immediate gratification) and “should” (acting based on consequences).

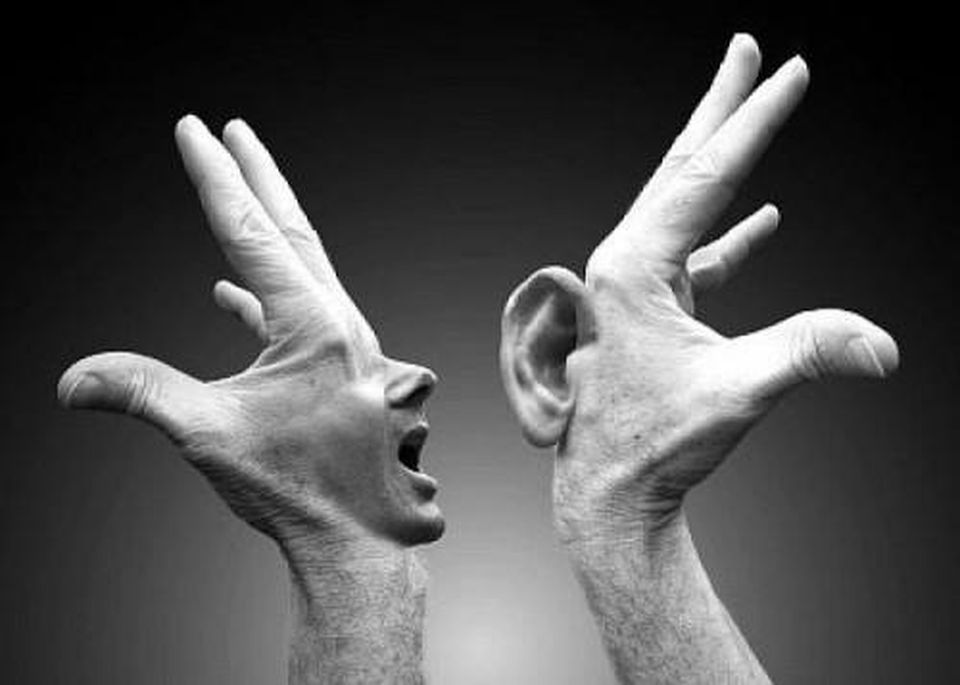

These internal conflicts naturally show up in our behavior—words, facial expressions, muscle tension, breathing, and voice. When all signals match, NLP calls this congruent behavior or congruence. For example, someone says they’re “confident” and their nonverbal cues match: head held high, relaxed shoulders, upright posture, steady breathing.

Our perception of someone else’s congruence is shaped by our own experiences—what behaviors we expect to go together. For instance, if you’re used to high-status people acting arrogant, a friendly high-status person might seem incongruent to you.

But when signals don’t match—someone says they’re “confident,” but their head is down, voice is quiet, posture is slouched, and breathing is tense—these are signs of incongruence. They might feel they should say they’re confident, but don’t actually feel it. People often say what they think others want to hear, what’s more acceptable, or what benefits them, or they’re just too shy to tell the truth.

Congruence and Rapport

Congruence reflects a person’s internal harmony and strengthens rapport. You’ve probably heard the phrase, “He really believes what he’s saying.” That’s a sign of congruence. Congruent people inspire others, attract followers, and are seen as “genuine.”

Usually, we compare the content of speech and nonverbal cues:

- “Can I get to know you?”

- “No.” (while nodding in agreement)

But the content must be evaluative. If someone shares information that can’t be conveyed nonverbally—like “my salary is $50,000,” “it’s 8 PM,” or “I’m going to the cabin tomorrow”—there’s nothing to compare. But if they’re expressing an attitude—like, “I like it,” “I believe,” “I’m confident,” “it’s hard,” “I’m upset,” “I’m happy”—then you can calibrate for congruence.

Nonverbal signals can also conflict. For example, someone gestures more with their right hand while their left hand is idle—this is also incongruent. So, compare signals from both sides of the body.

You might remember from school that people have two brain hemispheres: the left is more logical, the right more emotional and synthetic. The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body, and the right controls the left. This is a simplification, but it works for our purposes. Symmetry—balanced movement of both hands, equal muscle tone on both sides, upright posture—suggests “heart and mind are in harmony.”

Recognizing Genuine States

States are complex and show up in everything from voice to posture. Experience shows that when someone is truly happy, they smile, their voice is higher, and their posture is straighter. For example, “crow’s feet” (wrinkles at the corners of the eyes) are a good sign of a genuine smile. If the smile is fake, there won’t be wrinkles at the outer corners of the eyes—different muscles are used.

Example of a “fake” smile: other facial muscles are at work, and “crow’s feet” don’t appear. This might be good for the skin around the eyes and glossy magazine photos, but not for authenticity.

Here, you’ll need to rely on your own experience—how people usually express joy, sadness, grief, or confidence.

This is where calibration comes in—observe how someone genuinely expresses a state and compare it to when they do it “on purpose.”

Simultaneous and Sequential Congruence

So far, we’ve talked about simultaneous congruence—when both signals happen at the same time. But there’s also sequential incongruence.

First, one signal, then the opposite. Sometimes, this even happens within the same system:

- “Yes, of course. Although… Maybe… You know…”

- Or when someone asserts something, then shrugs—a sign of internal disagreement.

Ever get stuck in a doorway? You step out, remember you forgot something, step back, then realize it can wait. You leave, but feel pulled back. That’s sequential incongruence.

Sequential congruence is seen as a consistent opinion or steady pursuit of a goal. Look for consistency and follow-through in actions:

- Said they’d repay a debt—and did.

- Agreed to visit the in-laws on Saturday—and went.

- Promised to lose weight by summer—and did.

How to Demonstrate Congruence

Calibrating sequential incongruence—like a confident statement followed by a shoulder shrug—can help spot when someone is lying. However, incongruence itself doesn’t mean someone is lying, just that they’re internally conflicted.

Congruent communication usually consists of several main messages. Note that we don’t just demonstrate emotions like anger or joy, but also respect, agreement, or submission.

- Agreement: agreement + confidence + positivity. If agreeing with something unpleasant: agreement + confidence + negativity.

- Respect: always includes a message of submission, showing the “respected” person is higher in status.

- Guilt: submission + moderate negativity, directed at oneself. If blaming someone else: superiority + importance + negativity, directed at the guilty party.

- Contempt: superiority + negativity + confidence. If your opponent shows contempt after negotiations, they feel they’ve outsmarted you.

- Fear: negativity + importance.

- Anger: negativity + importance + activity. Anger is more active than fear; in anger, you move toward danger, in fear, away from it.

- Openness: moderate doubt + low speed + passivity, directed toward listeners.

- Motivation “Toward”: activity (a sign of motivation) + confidence + positivity.

- Motivation “Away From”: activity + confidence + slight negativity.

- Determination: strong motivation: activity + strong confidence + slight negativity.

- Happiness: positivity + importance + confidence.

In your free time, try breaking down emotions into their main messages.

Exercise: “Congruent Demonstration”

In groups of 4-5 people:

- The leader’s task is to congruently say an evaluative phrase, such as:

- You appeal to me.

- I’m not sure about the outcome.

- I’m surprised by how things turned out.

- I doubt things are that bad.

- This rain annoys me.

- I’m glad to see you.

- It’s important that you’re listening to me.

- I’m happy to talk about my family.

- The rest of the group listens and evaluates the level of congruence. If it’s low, they give sensory-based feedback on how to increase congruence.

- The leader has up to three attempts, then roles switch to the next person.

- Duration: 20 minutes.

In Summary

- What is congruence? Congruence is the consistency of information simultaneously conveyed verbally and nonverbally, or through different nonverbal channels. It reflects a person’s internal harmony and integrity.

- How can it be used? In counseling, increased congruence is a sign of problem resolution. Incongruence in a context signals internal conflict. In communication, your own congruence increases listener trust. By calibrating others’ congruence, you can gauge their confidence in their words.

- What types of congruence and incongruence exist? There is simultaneous and sequential congruence (and incongruence). Simultaneous congruence is when words and nonverbal signals match—like saying “this is important” while gesturing upward and tensing your arm, or symmetrical hand movements during a speech. Sequential congruence is consistent support for a position or goal pursuit. Simultaneous incongruence is a mismatch between words and nonverbal cues—like saying “I’m happy” while pursing your lips and frowning, or mixed nonverbal signals—nodding while tensing your shoulders and holding your breath. Sequential incongruence is when someone agrees, then disagrees, then agrees again.