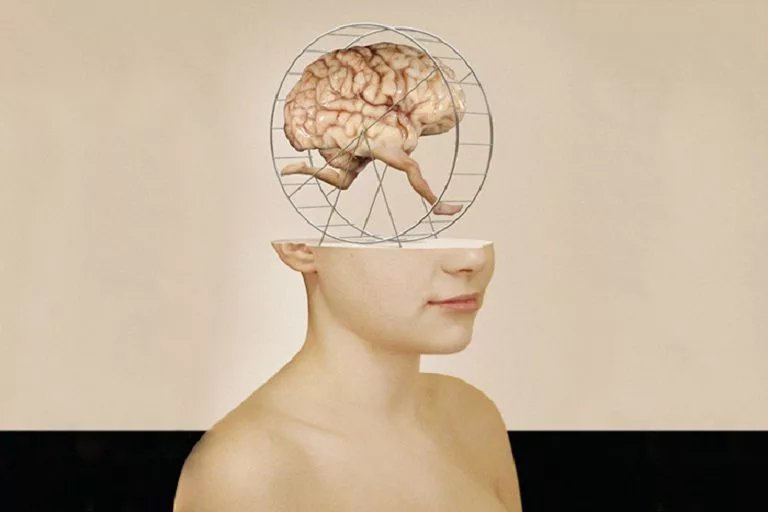

Common “Bugs” in Human Psychology

We tend to see the world as whole, orderly, and logical. In reality, it’s quite different.

Confirmation Bias

People are good at perceiving information that supports their point of view, while “inconvenient” facts are often ignored—sometimes unconsciously. It’s hard to be unbiased about things that matter to us. Even the most convincing evidence against our beliefs can go unnoticed or be dismissed as a mistake, deception, or something insignificant. We also tend to sympathize more with those who share our views and are more likely to choose friends from among them.

The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon (Frequency Illusion)

When you learn something new, it suddenly seems to appear everywhere. For example, after reading a book by a certain author, you start noticing their books with subway passengers, friends, and on store shelves. Medical students often experience this: after studying symptoms, they “find” many of them in themselves.

Transparency Illusion

Many people believe that when they lie, others can immediately tell. In a 1998 Cornell University experiment, students were asked to answer questions truthfully or with lies, and the audience had to spot the lies. Students thought their lies would be detected 50% of the time, but in reality, observers succeeded only 25% of the time. The reverse effect also exists—when someone thinks they can “see through” others, but in fact, they’re just projecting their own experiences, expectations, or fears onto someone else’s behavior.

Illusion of Control

Psychologist Ellen Langer coined this term to describe people’s tendency to overestimate their influence over events. In one experiment, participants were asked to press or not press a button, while a light randomly turned on or off. Even though the button had no effect, many claimed they could control the process. In similar experiments, the opposite effect was shown—sometimes people underestimate their ability to control events, depending on their mood or investment in a positive outcome. The illusion of control can help us believe in success and persist, but it can also lead to costly mistakes.

Gambler’s Fallacy

When you flip a coin, the chance of getting heads is obviously 50%. But if the coin lands on heads several times in a row, people betting on heads think their chances of winning decrease, while those betting on tails believe they’re “due” for a win. In reality, the odds remain the same as long as the conditions don’t change. Even if a coin lands on heads a thousand times, the chance of heads or tails on the next flip is still 50%. Gamblers often fall into this mental trap, continuing to bet after repeated losses, hoping their “bad luck” will eventually run out.

Conformity

For many, the opinions of others are very important. The habit of thinking and acting like everyone else is called conformity. This helped our distant ancestors survive and is often useful today, helping us make good decisions. However, conformity can be harmful when people support absurd ideas just to avoid standing out. Soviet psychologists once conducted an experiment where participants were shown two pyramids, one black and one white. Everyone, except the last participant, was instructed to say both were white. The last, unaware of the setup, had to choose whether to disagree or go along. Many chose to give the obviously wrong answer. The experiment was repeated years later with similar results.

Contrast Effect

If you put your hands in room-temperature water, it will feel hot or cold depending on whether your hands were previously on a hot radiator or in a bucket of snow. We perceive the properties of objects more vividly when we have something to compare them to. Try this experiment: place three bowls in front of you—one with ice water, one with warm water, and one with hot water. Put your right hand in the ice water and your left in the hot water. Then put both hands in the warm water at the same time. Your left hand will feel cold, and your right will feel hot. Marketers use the contrast effect: if an expensive item is placed next to an even pricier one, the first seems less expensive.

Pareidolia

In 1975, two spacecraft were sent to orbit Mars and took photos of the planet’s surface. One image caused a sensation: a hill that looked like a giant human face, dubbed the “Martian Sphinx.” Theories abounded until higher-resolution images showed it was just a play of light and shadow. This is called pareidolia—a type of optical illusion where the brain tries to find familiar features in objects. We “see” faces, people, and animals in clouds, and a shadow in a dim room can look like a stranger or a ghost.

Barnum Effect

Many people claim that horoscopes and fortune-telling describe their character, past, and future with uncanny accuracy. This is the Barnum effect, named after the famous American showman. Horoscopes and fortune-telling are usually vague, offering general information that people unexpectedly “recognize” as their own situation. The same phrase can be interpreted in many ways and applies to many situations. But people feel it’s about them personally. Marketers and alternative medicine practitioners, like homeopaths, often use the Barnum effect.

Belief in a Just World

Many believe in “what’s rightfully theirs” and that “wrongdoers will be punished.” Yet people aren’t always objective about their own actions, often justifying themselves and blaming circumstances. Meanwhile, others’ actions are more often attributed to their character or responsibility. Criminals sometimes blame their victims, saying it’s their own fault. It’s hard for people to accept that much of what happens in the world is random, and that concepts like “good,” “evil,” and “justice” are relative.

It’s not just the mind that has “bugs”—our bodies do, too.

Common “Bugs” in the Human Body

Unfortunate Lower Back

When early humans started walking upright, it was bad news for the spine. Degenerative diseases, herniated discs, and various pain syndromes are, to some extent, the price we pay for bipedalism. The lower back takes the greatest load. In addition, some people have a “bug” in their lower back they may never know about. Newborn vertebrae aren’t solid—they’re made of separate bones connected by cartilage. Over time, these fuse, but in one in four people, the process is incomplete, leaving the arch halves of the last lumbar or first sacral vertebra unfused. This usually doesn’t cause problems, and such people can even be professional athletes. If other vertebral arches don’t fuse (which is rarer), spinal function is often impaired and pain occurs.

Double Duty Organs

Some organs perform two functions, which can be more of a drawback than an advantage. For example, the pharynx connects to the mouth, airways, esophagus, and larynx. When we breathe, air passes through the pharynx to the larynx; when we swallow, the epiglottis covers the airway and food goes down the esophagus. This “intersection” between the digestive and respiratory tracts makes aspiration possible—saliva, food, or vomit can enter the airways, especially in unconscious people.

Another example is the genitourinary system. In men, the urethra serves both to pass urine and semen. In women, the urethral opening is right above the vagina, increasing infection risk. Also, the reproductive organs, especially in women, are close to the anus, which is surrounded by bacteria. The male urethra is long and narrow, passing through the prostate. Inflammation causes the urethral walls to swell, disrupting urination and sexual function.

Why We Walk in Circles

It’s often said that lost people walk in circles. In unfamiliar environments, like forests, people tend to walk in circles even though they think they’re moving straight ahead. Scientists first suspected leg length differences, thinking one leg might take longer steps. In 2009, German psychologist Jan Souman conducted an experiment, sending six people into German forests and three into the Sahara Desert, tracking them with GPS. When participants could see the sun or moon, they walked fairly straight. In cloudy weather or at night, they walked in circles. In another experiment, 15 people walked blindfolded—almost all walked in circles with a diameter of no more than 66 feet (about 20 meters). Scientists concluded that leg length and stride width aren’t to blame; the error occurs in the brain, turning a straight path into a circle. So in unfamiliar places, don’t trust your senses—find reliable landmarks.

Asymmetrical Humans

Some people are right-handed, others left-handed (and some are ambidextrous). The right and left brain hemispheres have different functions—this is called functional asymmetry. But the human body is asymmetrical in many other ways. The left foot is often slightly larger than the right, and leg lengths can differ. For most, the difference is less than 5 mm and goes unnoticed, but for some, it’s significant enough to require orthopedic shoes or surgery. In 70% of people, the right side of the chest is slightly larger than the left, the sternum is shifted to the left, and nipples are at different levels. Many women have a larger left breast, which can be noticeable and uncomfortable. No one has a perfectly symmetrical face. Usually, right-handed people have noses that tilt slightly to the right, left-handed people to the left. For most of us, the right side of the face is larger than the left, and facial expressions differ on each side.