Camp Psychology: Breaking the Human Spirit in Nazi Death Factories

Based on the works of Viktor Frankl and other survivors

The Goal of Nazi Concentration Camps

The primary objective of Nazi concentration camps was to destroy the human spirit. Those less “fortunate” were killed physically; those “luckier” were broken morally. Even a person’s name ceased to exist—replaced by an identification number, which prisoners eventually used even in their own thoughts.

Arrival and Dehumanization

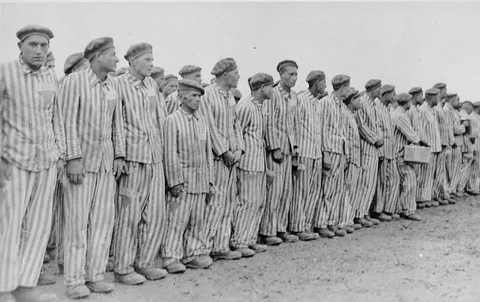

Upon arrival, prisoners lost their names and everything that reminded them of their previous lives, including their clothes and even their hair. Women’s hair was shaved and used as stuffing for pillows. People were left naked, as on the day they were born. Over time, their bodies changed beyond recognition—emaciated, with no trace of subcutaneous fat.

Before this, people were transported for days in cattle cars, unable to sit or lie down. They were told to bring their most valuable belongings, believing they were being relocated to labor camps in the East, where they would live and work for the benefit of Germany.

Future prisoners of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and other death camps had no idea where they were going or why. Upon arrival, everything was confiscated. Nazis kept valuables; “useless” items like prayer books and family photos were thrown away. New arrivals were lined up and marched past an SS officer, who silently pointed left or right. The elderly, children, the sick, and pregnant women—anyone who looked weak—were sent left; the rest, right.

As Viktor Frankl, a survivor and renowned psychiatrist, wrote in his book Man’s Search for Meaning: “I asked prisoners who had been there longer where my friend P. had gone. ‘Was he sent the other way?’ I asked. ‘Yes,’ they replied. ‘Then you’ll see him there.’ ‘Where?’ Someone pointed to a tall smokestack in the distance, flames lighting up the sky. ‘What’s there?’ I asked. ‘That’s where your friend is soaring in the heavens now,’ came the grim reply.”

Those sent “left” were doomed. They were ordered to undress and enter a “shower” room. There were no showers—only fake showerheads. Instead, Nazi guards poured Zyklon B crystals, a deadly gas, through the openings. Motorcycles were revved outside to drown out the screams, but it was never enough. Afterward, the bodies were checked to ensure everyone was dead. Early on, the SS didn’t know the lethal dose, so some survived the gassing and were killed with rifle butts or knives. The bodies were then moved to the crematorium. Within hours, hundreds of men, women, and children were reduced to ashes, which were used as fertilizer or dumped into the Vistula River.

Modern historians estimate that between 1.1 and 1.6 million people were killed at Auschwitz, most of them Jews. French historian Georges Wellers estimated 1,613,000 deaths, including 1,440,000 Jews and 146,000 Poles. Polish historian Franciszek Piper later estimated 1.1 million Jews, 140-150,000 Poles, 100,000 Russians, and 23,000 Roma.

Selection and Survival

Those who survived the initial selection were sent to the “Sauna,” where they were washed, shaved, and had identification numbers burned into their arms. Only then did they learn that their loved ones sent “left” were already dead. Now, their struggle for survival began.

Black Humor and Psychological Transformation

Viktor Frankl (prisoner number 119104) analyzed the psychological transformation all camp inmates underwent. The first reaction was shock, followed by what he called the “delusion of reprieve”—the belief that they or their loved ones would be spared. Then came black humor. “We realized we had nothing left to lose except our naked bodies,” Frankl wrote. “Even in the showers, we exchanged jokes to cheer each other up. At least there was real water coming from the pipes!”

Curiosity also emerged. “In the mountains, during a landslide, I once felt a detached curiosity: would I survive? Would I be injured? In Auschwitz, people experienced a similar detachment, as if their souls shut down to protect them from the surrounding horror.”

Prisoners slept five to ten to a bunk, covered in their own excrement, surrounded by lice and rats.

Death and the Fear of Living

The constant threat of death led many to contemplate suicide. “But I promised myself not to ‘run into the wire’—the camp term for suicide by touching the electrified fence,” Frankl wrote. Yet, suicide lost its meaning in the camp. How much longer could anyone expect to live—another day, a month? Only a handful survived until liberation. In the initial shock, prisoners no longer feared death; the gas chamber seemed almost a relief from the burden of suicide.

“In abnormal situations, abnormal reactions become normal,” Frankl observed. “Psychiatrists would confirm: the more normal a person, the more natural their abnormal reaction in an abnormal situation.”

Sick prisoners were sent to the camp hospital. Those who didn’t recover quickly were killed by SS doctors with carbolic acid injections to the heart. Nazis had no use for those who couldn’t work.

Apathy and Emotional Numbing

After the initial reactions—black humor, curiosity, and suicidal thoughts—came a second phase: apathy. Reality narrowed, and all feelings and actions focused on one goal: survival. An overwhelming longing for loved ones set in, which prisoners desperately tried to suppress.

Normal emotions faded. At first, prisoners couldn’t bear the sight of sadistic punishments inflicted on friends. But over time, they became numb, watching with indifference. Apathy and inner detachment were protective mechanisms, shielding the psyche from further harm. Similar reactions are seen in emergency doctors and trauma surgeons: black humor, detachment, and indifference.

Protest and Small Acts of Defiance

Despite daily humiliation, hunger, and cold, the spirit of rebellion persisted. Frankl noted that the greatest suffering was not physical pain, but moral outrage at injustice. Even knowing that protest could mean death, small acts of defiance still occurred. A word or gesture, if not fatal, brought temporary relief.

Regression, Fantasies, and Obsessive Thoughts

Life in the camp regressed to a primitive level. “Psychoanalytically oriented fellow prisoners often spoke of ‘regression’—a return to more primitive forms of mental life,” Frankl wrote. Prisoners dreamed of bread, cake, cigarettes, or a hot bath. Unable to satisfy basic needs, they experienced them in simple daydreams. When reality intruded, the contrast was unbearable. Obsessive thoughts and conversations about food dominated every free moment.

“Anyone who hasn’t starved can’t imagine the inner conflict and willpower it takes,” Frankl wrote. “Standing in a pit, swinging a pickaxe, waiting for the lunch break, wondering if bread will be handed out, feeling the piece of bread in your pocket, breaking off a crumb, putting it to your mouth, then putting it back—because you promised yourself to wait until lunch.”

Thoughts of food became all-consuming. Sexual desire disappeared. Unlike other all-male institutions, there was no sexual joking (except in the initial shock). Sexual motives didn’t even appear in dreams. However, longing for loved ones—unrelated to physical desire—was common, both in dreams and reality.

Spirituality, Religion, and the Need for Beauty

All “impractical” feelings and higher spiritual needs faded for most prisoners. Anything that didn’t bring immediate benefit—a piece of bread, a ladle of soup, a cigarette—seemed a luxury.

“There were two exceptions: politics and, notably, religion,” Frankl wrote. “People discussed politics everywhere, mostly rumors about the front. Religious aspirations, breaking through all the hardships, were deeply sincere.”

Despite psychological regression, some prisoners developed an inner world. Paradoxically, more sensitive people coped better than those with stronger constitutions. Sensitive souls could escape into their inner world, making them more resilient.

Some retained the need to appreciate beauty. “On the way from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp, we looked through barred windows at the Salzburg mountains lit by the setting sun. If anyone had seen our faces, they wouldn’t have believed these were people whose lives were over. Yet we were captivated by the beauty of nature,” Frankl wrote.

Occasionally, small concerts were held in the barracks—songs, poems, skits. Even exhausted, ordinary prisoners attended, risking missing their soup, because it helped them cope. Some even retained a sense of humor, which, though incredible under such conditions, served as a psychological weapon for self-preservation.

Psychology recognizes a specific term for the syndrome experienced by death camp survivors: concentration camp syndrome, a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It often becomes chronic, with symptoms like weakness, headaches, depression, anxiety, fears, hypochondria, memory and concentration problems, sleep disturbances, nightmares, and social withdrawal. The main symptom is survivor’s guilt.

The Devaluation of the Self

Most prisoners focused solely on survival. The devaluation of inner life, the numbering system, constant humiliation, and beatings led to a loss of self-worth for the majority. Many suffered from a sense of inferiority. In their previous lives, they had been “somebody.” In the camp, they were treated as “nobody.” Only a few, whose self-esteem was rooted in spiritual values, remained unshaken.

“A person unable to assert their dignity loses the sense of being a subject, let alone a spiritual being with inner freedom and value,” Frankl wrote. “They begin to see themselves as part of a herd, their existence reduced to animal survival.”

Bruno Bettelheim, another Austrian psychiatrist and camp survivor, noted that prisoners were infantilized and dulled through forced childlike dependence, chronic hunger, physical humiliation, meaningless rules and labor, destruction of hope, and denial of individual achievement. The urge to blend into the mass was both a product of the environment and a survival instinct: “The main rule was not to stand out or attract SS attention.”

Despite this, prisoners longed for solitude—a natural human need. But in the camp, there was nowhere to be alone.

Irritability and Animalization

Another psychological trait was irritability, caused by constant hunger and sleep deprivation, made worse by the lice and insects infesting the barracks. The entire camp system was designed to reduce people to an animal level, concerned only with food, warmth, sleep, and minimal comfort. The goal was to create obedient animals, to be killed as soon as their labor was no longer useful.

Loss of Future and Meaning

Camp life changed only those who lost all spiritual and human support. “Prisoners were most oppressed by not knowing how long they would be forced to stay,” Frankl wrote. “There was no end date. Even if discussed, it was so indefinite as to be limitless. ‘Loss of future’ became so ingrained that life was seen only as the past, as if already dead.”

The outside world seemed infinitely distant and unreal. Prisoners looked at it as if from the grave, knowing it was lost to them forever.

Selection wasn’t always just “left” or “right.” In some camps, new arrivals were divided into four groups: three-quarters went to the gas chambers; the second group was sent to forced labor, where most died from hunger, cold, beatings, or disease; the third group—mainly twins and dwarfs—were used for medical experiments by Dr. Josef Mengele, including live dissections, chemical injections into children’s eyes, castration without anesthesia, and sterilization. The fourth group, mostly women, were assigned to the “Canada” unit, sorting prisoners’ belongings and serving as personal slaves. The name “Canada” was a cruel joke, as in Poland it was slang for a valuable gift.

The Absence of Meaning

Doctors and psychiatrists have long known the close link between immunity and the will to live, hope, and meaning. Those who lost hope and meaning died quickly. Even strong elderly people who “didn’t want” to live soon passed away. In the camps, people often died of despair. Those who had resisted illness and danger finally lost faith, and their bodies succumbed to infection.

Frankl wrote: “The motto of all psychotherapeutic efforts could be Nietzsche’s words: ‘He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.’ Prisoners needed to find their ‘why,’ their purpose, to survive the nightmare. Woe to those who lost their sense of purpose and meaning—they lost the will to resist.”

Freedom and Aftermath

When white flags were raised over the camps, the psychological tension gave way to relaxation—but not joy. Freedom had become so abstract that it lost all meaning. After years of captivity, people couldn’t quickly adapt to new conditions, even favorable ones. Many, like war veterans, never fully adjusted, continuing to “fight” in their souls.

Frankl described liberation: “We shuffled to the camp gates, barely able to walk. We looked around fearfully, unsure if we would be struck or kicked. We reached a meadow, saw flowers, but felt nothing. That evening, people quietly asked each other, ‘Did you feel happy today?’ The answer was always, ‘Honestly, no.’ People had forgotten how to feel joy. It was something they would have to relearn.”

The psychological state of liberated prisoners can be described as depersonalization—a sense of detachment, as if everything was a dream too unreal to believe.