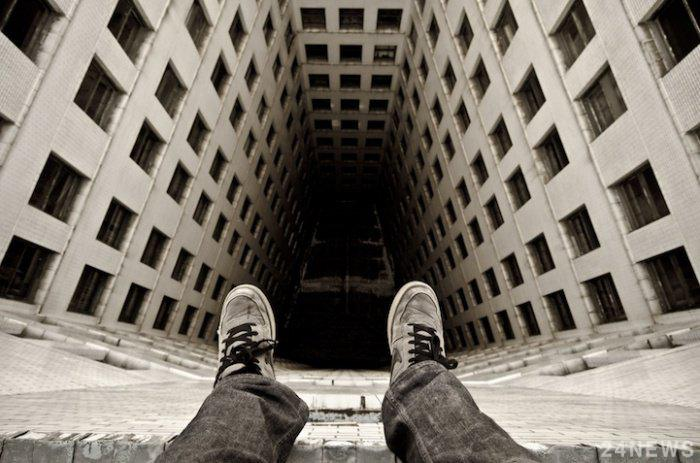

Russian Authorities Again Blame Anonymity and Social Media for Teen Suicides

The Russian Investigative Committee has proposed strict restrictions on media coverage of teenage suicides and school attacks, as well as the elimination of online anonymity. Recently, there has been an increase in the number of suicides among minors that were allegedly influenced by social networks, according to Sergei Korotkikh, an employee of the Main Directorate of Forensics of the Investigative Committee (IC) of Russia, during a roundtable discussion on “The Child’s Right to Safety.”

The report states that the number of suicide attempts among minors rose from 1,094 in 2014 to 1,633 in 2016. In the first quarter of 2017 alone, 823 such attempts were registered—more than half the total for the previous year.

Questionable Statistics and Political Rhetoric

It’s worth taking a closer look at the numbers presented by the IC. The Investigative Committee’s rhetoric is noticeably more cautious than that of politicians who pushed through last year’s so-called “death groups law,” often manipulating statistics to do so. For example, lawmaker Irina Yarovaya and other officials claimed there was a “spike” in child suicides. However, research by RosKomSvoboda found that, according to Rosstat data, there was actually a decrease in suicides among minors in recent years: 1,454 children under 14 died by suicide in 2011, 936 in 2014, 824 in 2015, and 720 in 2016. Despite this downward trend, Yarovaya and her colleagues misled the public and passed the controversial “death groups” law.

Regarding the IC’s data, the term “attempt” is vague, making it odd that law enforcement relies on it rather than on confirmed cases. There are also discrepancies between the IC’s numbers and Rosstat’s: “In 2014, 737 teenagers died during suicide attempts, and in 2017—692,” according to the report. These inconsistencies make it difficult to understand the logic behind the IC’s proposed preventive measures.

Media Influence and the “Death Groups” Phenomenon

The report notes an increase in suicides influenced by the media: from 22 cases in 2014 to 105 in 2017. Targeted online provocation was confirmed in two cases in 2015 and in 173 cases in the first half of 2017. This raises questions: How did investigators determine media influence on young people’s decisions? Which media outlets were involved? What exactly is meant by “provocative online influence”? Notably, the “spikes” in 2017 coincided with a media frenzy—fueled by both official and independent outlets—about so-called “death groups.”

These “death groups” received special attention. According to the report, they were unknown before 2014, but in 2015, two victims were confirmed members, 20 in 2016, and 287 in the first half of 2017. Again, the rise in these numbers seems to coincide with the authorities’ own media campaigns.

School Attacks and Social Media

The report also notes an increase in reports of school attacks, with related posts viewed over 75 million times. “Almost all attackers were registered on the social network VKontakte and were interested in mass killings, weapons, biographies of famous serial killers, and were members of ‘Columbine’ groups.”

According to the IC, minors’ interest in VKontakte is due to the availability of various materials, including videos, audio, photos, and images, which often contain profanity and promote violence.

The Role of the Media

A separate section of the report discusses the media’s role in creating “artificial interest” in these topics. After media coverage, the number of subscribers to “Columbine,” “school shooting,” and “mass murder” groups increased sharply. “It can be said with confidence that the media played a major role in what happened in Perm and Ulan-Ude,” the report states. Before media coverage, only hundreds knew about “death groups,” but afterward, millions did, leading to a surge in subscribers, according to Korotkikh.

Proposed Measures: Restricting Freedom Online

Korotkikh proposed strict limits on media coverage of teen suicides and school attacks. To combat these issues, the IC suggests “eliminating anonymity in the Russian segment of the internet, regulating social network registration procedures, requiring the use of accurate data to identify users from the moment their account is activated,” and “considering the possibility of registering on the internet exclusively through the government services portal.”

It’s clear that the authorities, under a questionable pretext and by manipulating statistics that actually contradict their apocalyptic narrative, are seeking to tighten internet controls. The IC, and its head Alexander Bastrykin in particular, have repeatedly proposed reducing Russians’ online freedoms, often misinterpreting events or even confusing one social platform for another.

Apparently, investigators do not fully understand what the internet is or how it works, relying on scare tactics reminiscent of the “analog era.”