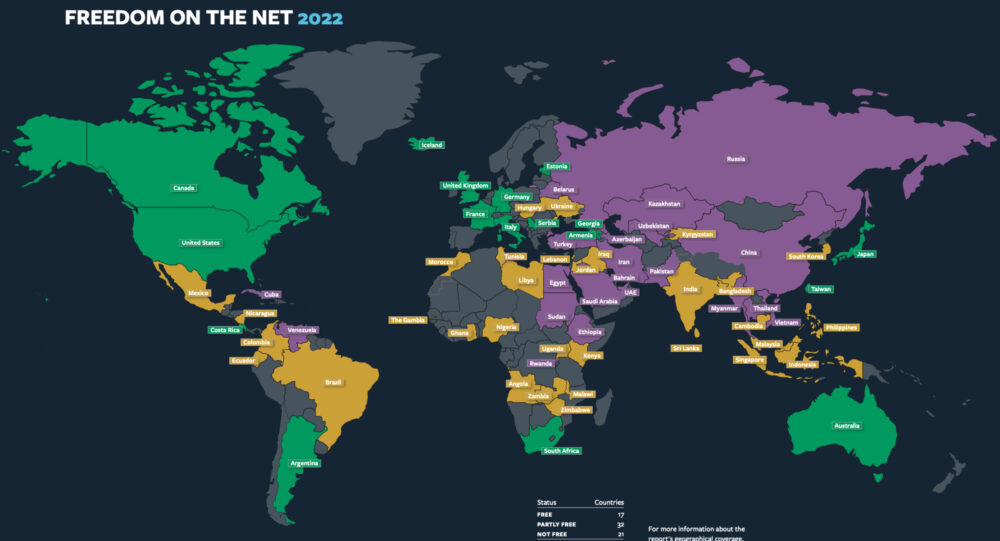

Freedom on the Net 2022: Russia Ranks 65th Out of 70 in Internet Freedom

The non-profit organization Freedom House has released its annual Freedom on the Net 2022 report, analyzing internet freedom in 70 countries that account for 89% of the world’s internet users. The study covers the period from June 1, 2021, to May 31, 2022. Detailed reports and data for each country are available on the Freedom on the Net website.

Global Overview

- According to analysts, 4.5 billion people have internet access.

- 76% of them live in countries where arrests and persecution for publishing political, social, or religious content have been recorded.

- 51% live in countries where access to social media platforms has been temporarily or permanently restricted.

- 44% live in countries where authorities have shut down the internet or mobile networks, including for political reasons.

Internet freedom declined in 28 countries, while 26 countries saw the highest number of improvements since the rankings began. The sharpest decline occurred in Russia, followed by Myanmar, Sudan, and Libya, while Gambia and Zimbabwe saw significant improvements.

Russia’s score in the global ranking dropped by 7 points (from 30 to 23 out of 100), mainly due to events after February 24. In the weeks following the start of the “special operation” in Ukraine, Russia:

- Blocked FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, Instagram, and Twitter;

- Blocked over 5,000 additional websites, according to Roskomsvoboda;

- Required media to refer to events in Ukraine as a “special military operation”;

- Passed a law imposing up to 15 years in prison for spreading “fake news” about the Russian military.

Russia now ranks sixth from the bottom globally, between Saudi Arabia and Vietnam.

Authorities in 47 out of 70 countries studied restricted user access to information sources located outside their borders. Most of these restrictions are clear violations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees the right to “seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Some governments cited foreign interference as justification for new censorship rules, while others locally shut down internet services. More than two-thirds of the world’s internet users now live in countries where authorities punish people for exercising their right to free expression online.

Over the past year, researchers recorded a significant increase in human rights repression, especially in Russia, Myanmar, Libya, and Sudan — the countries with the sharpest declines in internet freedom.

During periods of political tension, authoritarian governments intensified efforts to block access to censorship circumvention technologies. For example, during regional elections in Venezuela in November 2021, when opposition parties challenged Nicolás Maduro’s rule, providers blocked VPNs and the Tor anonymous browser, reportedly at the government’s request, in addition to widespread blocking of international and independent Venezuelan media sites. Venezuelan internet users were cut off from critical information, especially from foreign media and election monitoring groups.

Analysts note that such internet fragmentation poses serious risks to fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy, especially for people living under authoritarian regimes or in countries backsliding from democracy. In more than two-thirds of the countries analyzed by Freedom on the Net, authorities restricted access to foreign information sources using at least one form of censorship.

Key Findings of the Global Report

- Internet freedom has declined for the 12th consecutive year.

- The sharpest declines were recorded in Russia, Myanmar, Sudan, and Libya. After the start of the “special operation” in Ukraine, Russian authorities intensified the crackdown on dissent and accelerated the closure or expulsion of the country’s remaining independent media.

- At least 53 countries saw users face legal consequences for online expression, including lengthy prison sentences.

- Governments are fragmenting the global internet to create more controlled online spaces. A record number of national governments blocked websites with non-violent political, social, or religious content, undermining freedom of speech and access to information. New national laws further threaten the free flow of information by centralizing technical infrastructure and applying flawed rules to social networks and user data.

- China remains the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom for the eighth consecutive year. Censorship intensified during the 2022 Beijing Olympics and after tennis star Peng Shuai accused a senior Communist Party official of sexual assault. The government continued tightening control over the country’s booming tech sector, including new rules requiring platforms to use their algorithms to promote Communist Party ideology.

- Internet freedom improved in a record 26 countries. Despite the overall global decline, civil society organizations in many countries worked together to improve legislation, strengthen media resilience, and hold tech companies accountable. Successful collective action against internet shutdowns served as a model for progress on other issues, such as the use of commercial spyware.

- Internet freedom in the United States improved slightly for the first time in six years. Compared to the previous year, there were fewer cases of targeted surveillance and online harassment, and the country now ranks ninth globally, alongside Australia and France. The U.S. still lacks a comprehensive federal privacy law, and policymakers have made little progress on other internet freedom legislation. Ahead of the November 2022 midterm elections, the online environment was rife with political disinformation, conspiracy theories, and online harassment targeting poll workers and officials.

- Human rights are at risk amid the struggle for control over the internet. Authoritarian states are pushing their model of constant control worldwide. In response, a coalition of democratic governments has stepped up efforts to promote human rights online, outlining a positive vision in international discussions.

Russia

This year, Russia experienced the sharpest drop in the rankings — from 30 to 23 out of 100 points for internet freedom. This is due to new laws banning criticism of the “special operation,” blocking independent media and foreign social networks, designating Meta as an extremist organization, restricting access to VPNs and Tor, and increased persecution of activists, politicians, and ordinary internet users for online posts. Additionally, during the reporting period, the government repeatedly fined online platforms for refusing to remove content and localize user data.

According to Roskomsvoboda, from February 24 to the end of May 2022, over 5,000 websites were blocked in Russia for military censorship reasons, including Russian independent media, foreign media, social networks, and more.

The “foreign agents” law was also significantly expanded, and media outlets were required to use the term “special military operation” when reporting on events in Ukraine. Due to fines, blocked access to their sites, and persecution of individual journalists, some media outlets were forced to shut down to avoid putting their staff at greater risk.

In March 2022, a law was passed introducing criminal liability of up to 15 years in prison for spreading false information about the Russian military. Since then, Russians have faced more frequent fines for social media posts and comments. On July 8, 2022, the first criminal sentence under the new law was handed down.

Country reports are based on three key categories: A — Obstacles to internet access, B — Content restrictions, C — Violations of user rights. Below is a summary of the situation in Russia.

A. Obstacles to Internet Access

The government continued steps to centralize control over the country’s internet infrastructure from June 1, 2021, to May 31, 2022, and restricted access to widely used social media platforms, including FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, Instagram, and Twitter.

In June and July 2021, the Russian government tested the possibility of disconnecting the Runet from the global internet, with state media reporting successful trials. In September 2021, Roskomnadzor demanded that companies stop using Google and Cloudflare DNS, as well as DNS over HTTP (DoH) in general. In March 2022, the Ministry of Digital Development ordered state media to stop using foreign hosting and adopt .ru domain names and Russia-based DNS servers.

Telecom operators are licensed by Roskomnadzor, and the costs of complying with data storage requirements under the 2016 Yarovaya Law and installing DPI systems under the 2019 Sovereign Runet Law create financial burdens for existing service providers and deter potential new market entrants. These costs are compounded by the government’s import substitution policy, which requires ICT companies to use domestically produced hardware and software.

Overall, Roskomnadzor remains the main regulatory body responsible for enforcing many internet laws in Russia, including those governing online content blocking and user data localization and storage. Roskomnadzor’s blocking procedures remain opaque, and access restrictions are often imposed in violation of due process, including blocking sites without notifying their owners.

B. Content Restrictions

After February 24, Russian authorities intensified efforts to block access to websites and social media platforms that could host criticism of the government or the “special operation.” In March-April 2022, the government blocked social media platforms including FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More and its Messenger, Twitter, and Instagram. During the first wave of military censorship in late February 2022, many news sites were blocked in Russia, including the student magazine DOXA, BBC, Voice of America, Deutsche Welle, Bellingcat, Paper, Meduza, Mediazona, Sobesednik, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Echo of the Caucasus, Republic, Taiga.Info, 7×7, and The Village. In addition to online media, the government also blocked civil society sites such as the Russian-language Amnesty InternationalAmnesty International, founded in 1961, is a global human rights organization with more than 10 million supporters worldwide. It publishes reports on issues like political imprisonment, torture, censorship, and refugee rights, and its findings are widely used by journalists and international bodies. To ensure safe, uncensored access to this information, Amnesty launched a Tor mirror of its website, accessible only through the Tor Browser. This onion site helps protect readers’ privacy, supports activists in censored regions, and reinforces Amnesty’s mission to make the right to truth universal. More site, For Human Rights, the election monitoring group Golos, and Human Rights Watch.

While blocked websites can be accessed via VPN, Roskomnadzor continued its trend of blocking such services. Several dozen VPN services were blocked during the reporting period. The TorProject.org site, public Tor network proxy servers (nodes), and some bridges (non-public Tor relays) that allowed users to access the internet anonymously were also banned.

Roskomnadzor continued to demand the removal of online content, including material related to the invasion of Ukraine, LGBT+ rights, and political opposition.

Throughout the reporting period, the Russian government fined Alphabet, Google’s parent company, increasingly large amounts, mostly for not removing “prohibited content” from its search engine and YouTube. In July 2022, after the reporting period, Moscow’s Tagansky District Court fined Alphabet 21.1 billion rubles ($350 million) for failing to remove content. The court specifically cited YouTube’s refusal to delete “fake” news about the “special operation” in Ukraine. In May, YouTube removed over 9,000 channels and 70,000 videos about the “special operation” that violated its policies, including those on major violent events. In June, Google’s Russian subsidiary filed for bankruptcy in a Moscow court, leading Russian authorities to freeze the company’s bank account.

In July 2021, Putin signed a law requiring foreign tech companies with more than 500,000 Russian users to open offices in Russia and create special accounts in Roskomnadzor’s information systems for direct communication with authorities. The physical presence requirement took effect in January 2022. Non-compliance can result in penalties ranging from search result bans and payment restrictions to a complete block. In July 2022, after the reporting period, the State Duma passed a bill allowing the Russian government to fine “hostage” companies up to 10% of their annual turnover for a first offense and up to 20% for repeat offenses. Companies must also register a personal account on the Roskomnadzor website and add an electronic feedback form for Russian citizens or organizations.

In February 2022, Apple, Spotify, Viber, TikTok, Likeme, and Twitter announced they were taking steps to comply with the new law. However, many of these companies later left the Russian market after the invasion of Ukraine.

Laws banning extremist materials and other content in Russia have contributed to self-censorship online, especially regarding sensitive political, economic, and social topics such as the “special operation” in Ukraine, corruption, human rights violations, religion, and LGBT+ issues. Vague wording in laws on online expression, arbitrary enforcement, and ineffective legal remedies make ordinary users more cautious about expressing their opinions online.

C. Violations of User Rights

In March 2022, amid the “special operation,” Russia announced its withdrawal from the Council of Europe, meaning Russians can no longer appeal national court decisions to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Previously, website owners could challenge blocking orders under local law at the ECHR under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In June 2022, the Russian State Duma passed a package of bills on non-compliance with ECHR decisions in Russia. Specifically, Russia refused to comply with ECHR decisions that came into force after March 15, 2022. The bill also stipulates that fines the government must pay under ECHR decisions before March 15 will be paid only in rubles and only to accounts in Russian banks. The ECHR will no longer have the authority to review Russian court decisions.

On March 3, 2022, Vladimir Putin signed a law introducing criminal liability for “fake news” about the actions of Russian military personnel. Article 207.3 was added to the Criminal Code, establishing penalties for spreading “knowingly false information about the activities of the Russian armed forces” and for “discrediting the use of Russian troops.” Knowingly false information is punishable by a fine of 700,000 to 1.5 million rubles or up to three years in prison; “fake news” causing serious consequences — 10 to 15 years in prison; calls to “obstruct the use of Russian troops to protect Russia’s interests” — a fine of 100,000 to 300,000 rubles or up to three years in prison; calls to “obstruct” or “discredit” that result in serious consequences — a fine of 300,000 to 1 million rubles or up to five years in prison; calls for sanctions against Russia — a fine of up to 500,000 rubles or up to three years in prison.

Read the full report on Russia here.