How to Prevent Panic in Emergency Situations

Emergencies can happen to anyone, and even the most level-headed people can be affected by panic. Knowing how to recognize the onset of panic and how to counteract it is crucial for your safety and the safety of those around you. This article explains what panic is, how it develops, and what you can do to prevent it in crisis situations.

What Is Panic?

Panic is a sudden, overwhelming fear that clouds judgment and causes people to act irrationally and chaotically. It can be triggered by any event that threatens life or well-being, such as wars, natural disasters, revolutions, riots, and more. The problem with panic is that it can suppress your skills, abilities, and even your basic survival instincts. While survival is still possible, it often comes down to luck rather than preparedness.

It’s important to control yourself even in a crisis, but this is difficult because panic is “contagious.” If someone near you starts to panic, there’s a high chance you will too, especially if you don’t understand what’s happening.

For example, imagine you’re in a movie theater and suddenly the lights go out, you see sparks, and smell smoke. The logical response is to evacuate calmly. But if even one person starts screaming and rushes for the exit in a panic, others will follow, making it very hard to stay rational.

The “Anatomy” of Panic

Everyone has their own panic triggers—some fear heights, others spiders or snakes. Sometimes, even just seeing a picture of the trigger can cause a physical reaction. However, panic is a universal human response. Anyone can panic if placed in the right (or rather, wrong) environment, especially when faced with something unfamiliar and unexpected.

Panic typically develops in several stages, each with its own physical and psychological reactions:

- Apathy

The initial reaction to a growing crisis, often called the “calm before the storm.” People show little activity and make unproductive preparations for the coming trouble. Many ignore the danger, believe it won’t affect them, or assume someone else (like authorities) will save them. This fatalism and inaction are major reasons for losses when situations go from bad to worse. - Disorganization

At this stage, the crisis can no longer be ignored, but it’s too late to prepare. People start asking unproductive questions like “What should we do?” or “Who’s to blame?” Actions become instinctive rather than logical. For example, during a fire, people may rush to the main exit instead of using alternative emergency exits, causing dangerous crowding. - Panic

This is the stage where people act purely on instinct—running, fighting, hiding, or freezing—depending on their temperament. Some aggressively push toward the exit, while others become paralyzed. Reasoning with someone in this state is useless; survival depends on luck and outside help. - Dependence

After the immediate danger has passed, people may remain passive and irrational. Survivors look for someone to lead them and will follow anyone who acts purposefully. Emotional instability is common—people may become hysterical or aggressive. This phase lasts differently for everyone; some recover quickly, others need more time.

How to Prevent Panic

The most important phase to address is apathy. While people may not want to do anything, this is the best time for a leader to step up and guide a group toward productive preparation. The goal is to reduce the element of surprise, which is a major trigger for panic.

If you’re prepared, you can help your friends and family get ready for the most likely emergencies. When disorganization sets in, a leader should take charge, act confidently, give clear and simple commands, and assign tasks directly to individuals.

If there’s no clear leader, remember: your first reflexive reaction is probably wrong. Pause for a few seconds, consider alternatives, evaluate them, and only then act. Be ready to change your plan as the situation develops. For example, if you see a crowd at the main exit, turn around and head for an alternative exit instead.

Pay attention to those around you—help those who are frozen in fear, and try to isolate or calm down anyone acting aggressively. Anyone actively panicking can trigger panic in others nearby.

How to Recognize Panic

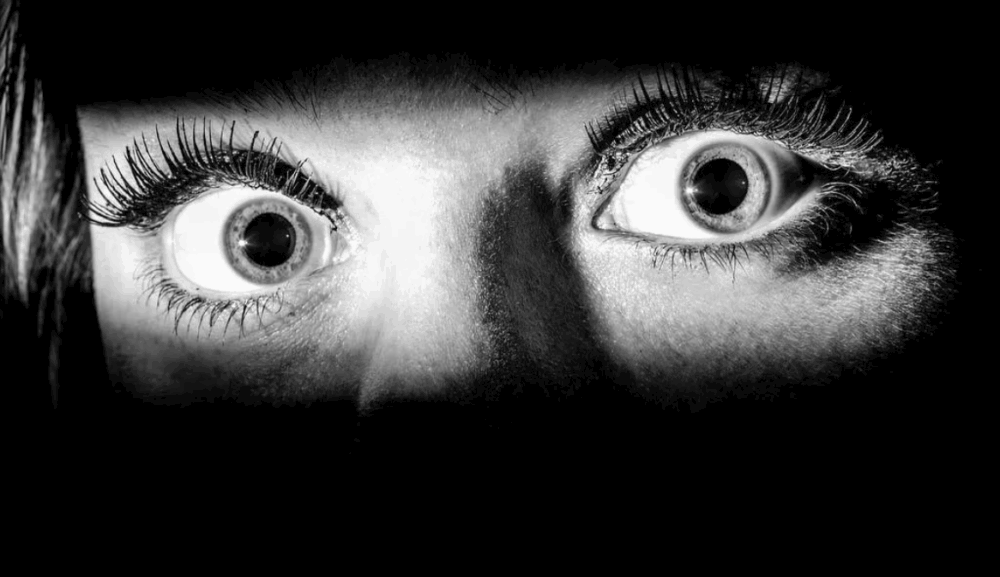

Most people won’t try to hide their panic. Key signs include dilated pupils, rapid eye movements, frequent blinking, hiding their face, covering their head with their hands, or hiding under tables or other “safe” places.

Overcoming Fear

Panic triggers are individual, but they always involve some kind of fear. Fear is often a result of feeling out of control. That’s why people with phobias try to control themselves and their environment as much as possible, often justifying irrational actions with rational arguments.

It’s normal to be afraid—there’s nothing shameful about it. In many cases, you can learn to control your fear enough that it doesn’t stop you from acting productively. Here are some tips (note: these methods may not work for everyone, so consult a psychologist before trying them):

- Accept your fear. It’s a normal state—you’re not losing your mind. Remember, it will pass. Don’t try to suppress or fight it; that rarely works.

- Get used to your trigger. Regularly look at what you fear and resist the urge to run away or close your eyes. Observe, evaluate, and get used to it. Remind yourself that it’s not actually threatening you right now.

- Don’t run away, even if you want to. You can step back or move away, but keep observing your trigger. Try to control your behavior. If it becomes too much, step away, calm down, regain control, and try again later.

- Learn to expect the best, not the worst. This shift in mindset can help. For example, if you’re afraid of heights and find yourself in an open elevator, focus on the fact that it will soon be over and that the elevator will safely take you where you need to go.

Conclusion

Phobias and fears can be serious obstacles to survival in extreme situations. That’s why it’s so important to learn to act despite them, if not overcome them entirely. This requires preparation, including deliberately putting yourself in unexpected situations to build experience and adaptability. The more prepared you are, the better you’ll be able to prevent panic when it matters most.