Facebook Asked New Users for Email Passwords to “Verify Address”

It seems that FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More is quickly becoming a prime example of insecure practices on the internet. Just two weeks ago, there was widespread discussion about why the company’s engineers were logging user passwords and storing them in plain text on Github. Now, there’s another surprising case. As it turns out, some new users were asked by FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More to provide the password to their email account—the one they used to register—in order to confirm their registration.

It’s hard to imagine how any engineer thought this was a good idea, or why no one objected. Such a practice is extremely rare these days, though it has happened before. For example, the now-defunct MySpace also used to ask users for their email passwords during its heyday.

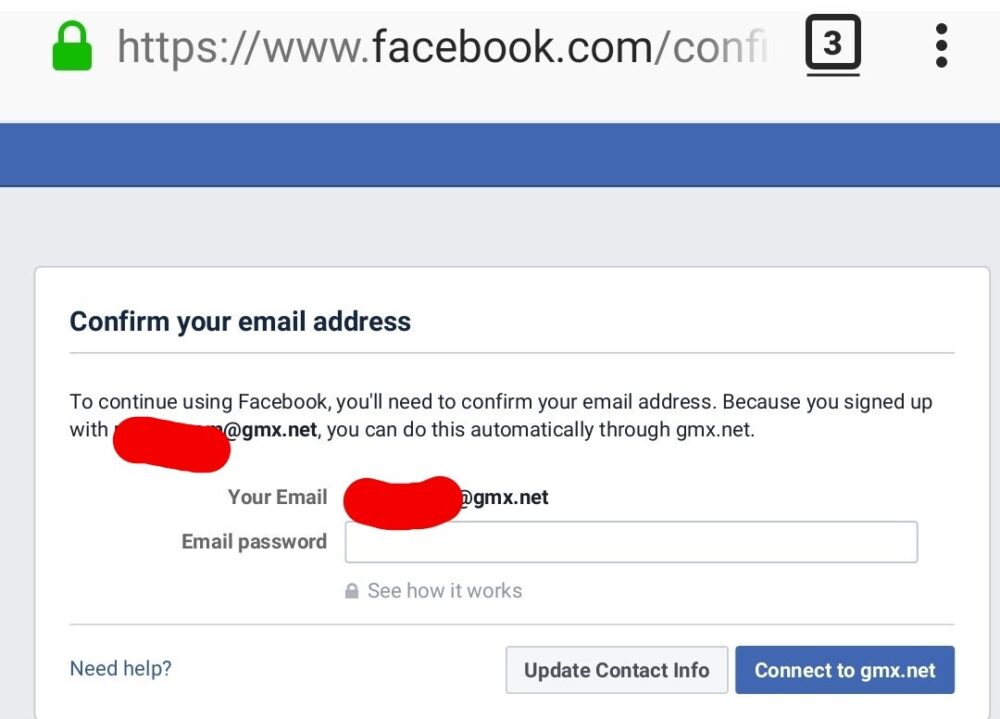

“To continue using FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, you need to confirm your email address,” read the message. “Since you registered with [email address], you can do this automatically through your email provider,” the message continued (as shown in the screenshot above), where FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More asks the user to enter their email password.

“This is beyond the pale,” said security consultant Jake Williams. “They should not be accepting your password or processing it in the background. If this is required to register for FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, you’re better off not signing up.”

In an official statement, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More said it does not store users’ email passwords. The company also announced plans to completely discontinue this practice: “We understand that password verification is not the best way to confirm an email address, so we are going to stop offering it,” a spokesperson said.

It’s unclear how widespread this practice was, but FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More representatives emphasized that users could bypass the password requirement and activate their account using more familiar methods, such as a code sent to their phone or a link sent to their email. However, these options were only available if the user clicked the “Need help?” link in the lower left corner of the page, which is hardly intuitive navigation.

Apparently, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More requested email passwords mainly from “suspicious” users—for example, those registering via Tor or VPN, or using unusual or disposable email addresses. Still, this is no excuse: “By taking this route, you’re essentially phishing for passwords you shouldn’t have!” wrote Twitter user e-sushi, who was the first to draw attention to Facebook’s questionable actions.

The password entry field included a link to more information, where FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More promised not to store users’ passwords. But given the company’s track record on user security, it’s hard to trust this claim 100%. Last year, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More was caught allowing advertisers to target users by phone numbers provided for two-factor authentication. More recently, it was revealed that these phone numbers were publicly searchable.

As usual, after the scandal broke, the company apologized and promised to end the practice.

New Data Leaks

To further confirm its reputation, it was recently discovered that two more FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More user data leaks were found publicly accessible on Amazon S3 cloud hosting.

The first was a 146-gigabyte database containing over 540 million records of user comments, likes, and reactions, all linked to individual accounts. The source was identified as the company Cultura Colectiva.

Additionally, a backup from the “At the Pool” app, which was integrated with FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, was found on Amazon S3. The database included fields such as fk_user_id, fb_user, fb_friends, fb_likes, fb_music, fb_movies, fb_books, fb_photos, fb_events, fb_groups, fb_checkins, fb_interests, and password. It appears that the password field contained user passwords for the At the Pool app itself, not for FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, but many users reuse the same (or similar) passwords across different sites.

Although the At the Pool database was smaller than Cultura Colectiva’s, it still contained 22,000 passwords in plain text. The At the Pool developer ceased operations in 2014 (the last archived copy of their site without a redirect is dated May 17, 2014). The parent company’s website now returns a 404 error. Unfortunately, this is little comfort to users whose names, passwords, email addresses, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More IDs, and other details were left exposed on S3 for an unknown period.

Both databases contained information about FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More users, including their interests, relationships, and interactions, which were accessible to third-party developers. After numerous scandals involving data leaks through third-party apps, FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More has tried to limit such access. However, as these leaks show, it’s hard to put the genie back in the bottle. User data has spread far beyond Facebook’s current ability to control it.

The Cultura Colectiva leak was first discovered by specialists from the UpGuard Cyber Risk team. They say they notified Amazon Web Services about the situation on January 28. The next day, AWS replied that the owner of the bucket had been notified that their data was publicly accessible. Three weeks later, nothing had changed. On February 21, UpGuard contacted AWS again, which responded the same day, saying they would look into further ways to address the situation.

It was only on the morning of April 3, 2019, after a Bloomberg journalist contacted FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More for comment, that the backup database in the S3 bucket named “cc-datalake” was finally removed from public access.

These two incidents highlight a fundamental problem with mass data collection: data doesn’t just disappear on its own. Old archives or backups can be forgotten or ignored. While these were third-party developer databases, they wouldn’t exist without FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More, and they are no longer under Facebook’s control. In each case, the platform facilitated the collection of personal data and its transfer to third parties, who were then responsible for its security.

As a result, the surface area for protecting FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More user data is vast and inconsistent, and the responsibility for its security lies with millions of app developers on the platform.

In other words, anything you do or save on FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More will eventually end up in the public domain and/or be used against you. Of course, this applies to all social networks.