NLP Training Materials by Richard Bandler: Shamanic States, Part 3

Many of us often do things we don’t want to do and behave in ways we don’t want to behave. This happens because we were born and raised constantly overloaded with all sorts of crazy information. Just think about what we were told growing up. At first, we had to study all these different religions, which contradict each other and even themselves. All of this was mixed in with school, which, if you think about it, is a bit like voodoo rules (silent letters everywhere—I keep listening for them, but I can’t hear them). They keep telling you, “There are so many letters in the alphabet, but some of them represent different sounds. There’s a long ‘A’ and a short ‘a’. So, if you see ‘A’, it could be ‘aaaa’ or just ‘a’, and really, there are lots of options. You can say it in a good tone or a bad one, you can say ‘aaaa’, or ‘aaeh’, or ‘aaoo’—all different things, but no one tells us about that. Then they say, ‘Yes, see, here it sounds like ‘a’, until a silent ‘e’ appears, then it’s ‘ae’ not ‘a’,’ and they just keep telling you all these stories.”

Here’s one of my favorites: when I first arrived in England, the first thing I saw was a portrait of George Washington. I was amazed—I thought, wasn’t he a traitor to the British? Wasn’t he the bad guy? I went up and read the inscription: “George Washington—revolutionary, patriot, and so on,” and I thought, Jesus, that’s great. If you’re a bad guy and become successful, you’re suddenly good. So, was he good or bad? Who knows? If Hitler had won World War II, could history have been told so that he became the savior of the world? Maybe. I like how the word “history” in English can be heard as “his story.” If you go back and look at the truthfulness of how events are told, history can change.

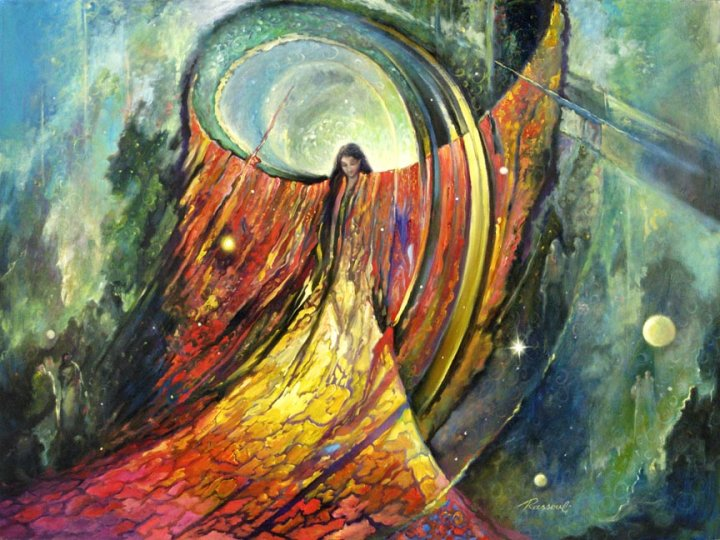

This whole weekend, we’ll be looking for things that help us feel better. The common thread is that it’s all about healing. Some things are related to sympathetic magic. The idea is, if you can get your thoughts to work, you can get someone else’s thoughts to work the same way. I think it’s like when you smile and someone smiles back at you. I don’t think that’s supernatural.

I’ve witnessed heart surgeries performed with hypnosis and acupuncture. If I had to go through something like that, I’d rather be unconscious—I’d choose a sledgehammer. I wouldn’t want to sit and watch in a mirror as someone cracks open my chest with a rib spreader. That’s a bit much for me. Some people are pretty good at leaving their bodies. I’d like to leave my body for a little while too, but I really don’t want anyone poking around in it while I’m gone. Especially with knives and forceps, pulling veins out of my legs—if I had to have a triple bypass, I’d just run away. They’d have to knock me out, and do it without me noticing.

It seems like every time I ended up in the hospital, something weird happened. I lost consciousness once just because I was misdiagnosed. I’m diabetic, but they were sure I had something unusual when I said I felt bad, all because I’d just come back from a long trip. Instead of checking the most obvious things, they started testing me for diseases you could catch in the jungle or somewhere else while traveling. They didn’t run the standard tests, and I fell into a coma; they only found the real reason when a doctor who was diabetic himself came in and recognized it just by the smell. Of course, after that, they ran a bunch of tests and confirmed the diagnosis (I have a genetic type of diabetes where antibodies destroy the pancreas). While I was in the hospital, they tried voodoo on me, tried post-hypnotic suggestion. They’d come in and say negative things to me all the time while I was on medication. Not only was I having a tough time coming out of the coma, but they also put me on sleeping pills. I don’t know about you guys, but something seems off about that.

There was a man there who kept having doctors come in and tell him, “You’re 67, and this surgery is pretty tough. Not waking up from it would be the best outcome for you.” How awful, I thought. I told him, “Listen, these people keep coming in and telling you bad things. I know you’re here and you can hear me now, so I’m going to do something that might seem strange.” I put my hand on his chest and moved it in time with his breathing; as I did, he suddenly started breathing, and I kept moving my hand. I started chanting—I don’t know why, but I’d heard it done in various temples. I’d also heard Native Americans do it, and their chanting sounds more convincing to me. The guy in India did it too softly; I like a stronger, even a little scary, sound. So I started chanting, and as my hand rose, I said, “O-o, a-a, ha-ya,” and kept going. Then I said, “Now you need to wake up.” Maybe I scared his unconscious body, because suddenly his eyes popped wide open!

By the way, did you know they give patients liquid pharmaceutical cocaine so that while you’re asleep, they try to wake you up? If that doesn’t work, it’s better to use a straw and say “ff-aa-tt”—maybe that’ll help the patient come to faster. That’s what the Aztecs and Mayans did. That’s how their postal system worked: a runner would dash through the jungle with a letter. For miles, if he stopped, someone would be there, take two tubes, fill them, put them to his nostrils, “ff-aa-tt”; “o-f”—the runner would yell and take off down the road. I’m not kidding, that’s how it worked.

When I read all those history books, I thought, “My God! Why did we forget all this?”

They used the same substances, with some additions, to put people into a state where they could talk to the dead. One of my enlightening experiences happened when I went to the jungle to see a man; a guy from a pharmaceutical company told me there was a healer in the jungle, but he wouldn’t tell them anything. He just didn’t like them; in fact, he’d cursed them from coming near his home. This healer did amazing things, and the pharmaceutical people couldn’t figure out what recipes he used. This guy was a real medic—just imagine, a medic in the jungle. He didn’t have a pharmaceutical lab, or a research center with a staff of 150 and microscopes—nothing like that. But he had something that let him heal people. He had a forest full of all sorts of things; I thought, maybe he won’t tell us how he heals, but at least he’ll show us where he does his research. The pharmaceutical guys said, “It must be passed down from generation to generation.” I argued, “But what if something new comes up? Someone had to figure it out.” They kept saying, “All this guy does is climb a 200-foot tree, grab a couple of bugs from a flower, mix them with some leaf, give it to someone, and they’re cured of anything.” Honestly, that’s how it was.

So I sent one of the guys to get me a satellite phone. Great thing—you can use it anywhere in the world. Now they’re tiny, but back then it was a whole suitcase with its own dishes and everything. He also found translators, and had to crawl into a cave full of snakes. When I first talked to him, I asked how he was doing, and he said, “They have the biggest scorpions you’ve ever seen.” He was washing his socks and stepped on a scorpion, got stung, got bitten by mosquitoes, almost got bitten by a snake, but someone stopped it. He thought it was a stick and tried to pick it up. They had to travel by motorboat, then go through rapids, reach the place, go to the village, and walk back. Eventually, they found the village where the healer lived. He wasn’t too eager to cooperate, so I decided to give him a gift. I thought maybe that would get his attention. I asked the translator to go and give him a present; what could interest this guy? Obviously, people had already tried to impress him with all sorts of Western gadgets, so to get his attention, I sent him a deity stone from a culture different from his own. Actually, it was a sample from the British Museum’s collection, which I covered with polymer clay, making it three times bigger. I put marks on it that looked like hieroglyphs, then thought that wasn’t enough, so I added magical symbols I’d seen in some books. So I sent the healer this stone as a gift, and he was really impressed.

By the way, I didn’t like the eyes on this deity stone, so I put my own in—took them from a doll. There was a doll belonging to a visiting girl (I probably shouldn’t have done that), but you know how dolls have those creepy, unblinking eyes? So I took the eyes out, drilled holes, and put them in the stone. I removed the eyelashes because it looked too scary, left just the doll’s eyes. The healer set the stone down, stared at it for a long time, then asked the translator, “What do you want?” He replied, “We understand you won’t give us your magic, and we don’t need your magic. All we want is to understand how you know which components to take from the forest and mix when you need to cure something new, something you don’t have a recipe for.” The healer turned and said—quote unquote—the translator didn’t understand the answer and kept asking me. As I said, he wasn’t the sharpest, so he called me and said, “Listen, I asked him your question, and he said he asks the forest?” He asked, “What do I do now?” I told him to go back and ask, “Where?” The guy sitting next to me looked at me in surprise and said, “What?” I explained, “You see, that’s the essence of the meta-model.”

The essence of the meta-model is to get information that lets you reconstruct behavior. If someone comes to a psychotherapist and says they’re depressed, you ask about the things that help you reconstruct the behavior, because you need to know not about the state of depression, but about how the person gets into that state. So when someone comes to you and says they’re depressed, you ask, “How do you know?” The thing is, the same process that lets a person enter that state helps you stop it. If a shaman can find out how to heal people by asking the forest, the first thing I want to know is—where. Because if he says “everywhere,” then that’s not the point. But he must have some way, since he says he asks the forest—not the trees or the gods, but the forest. So the guide asked, and the healer didn’t answer with words; instead, he said he needed to go somewhere.

They went together, and I didn’t hear from the translator for four days. Apparently, they had to visit all sorts of “God help us” places: climbing rocks, going down into stinky lowlands, and many other places. Eventually, they came to a lagoon. In the middle of the lagoon was a tree, and the healer paddled over, climbed up, and pointed to that tree. The translator called me, saying, “He brought me to this place.” He called me during the day—I was half asleep. “So you’re there?” I said. He answered, “Yes,” and I asked him to describe the area, which he did. I asked what illnesses he had. He was confused. I asked again, “Do you have any blisters? Anything?” He said, “Well, I have bites,” so I told him I wanted him to paddle over, stand on that spot, and ask the forest how to get rid of them. He agreed. This guy was a pretty good actor. He’d taken art and dance lessons—he could even do ballet. He came back and said, “I asked the forest, but nothing happened.” I told him to get into it. Go into a deeper altered state—you’ve been in trance before. I added, “You really need to believe you’ll get an answer—then tell me what happens.” A few minutes later, he came back and said, “I saw a picture.” I said, “Draw it—you have paper, right? Draw it and show it to the healer.” So he drew the picture and showed it to the healer, who went into the forest, brought back a plant, mixed everything, added some dirt, mixed it again, boiled it over a fire, and then smeared it on the translator’s legs. The next morning, all the bites were gone.

I know scientists will say maybe the shaman already knew what could heal it—they always have excuses. But they can’t explain where the picture came from, showing the plants the healer later brought. Maybe he already knew, but now we need to figure out: did the shaman communicate it to the translator psychically? Or does the forest actually have consciousness? In my opinion, if a tree knows when another tree is being killed, if yogurt knows when you want to eat it, I’m not at all surprised if something as big as a forest, the earth, or the universe can have consciousness, besides the consciousness we have as individuals. I don’t know.

How is it that cultures all over the face of the Earth, no matter how far apart they are, all started worshipping gods? How could they do that without talking to each other? There they are, on some unknown island in the middle of nowhere, in Burma, with no connection to the outside world, and yet they worship gods, and all the gods have something in common. Some are powerful, some not so much, but they all do something—good and bad. There are gods you pray to so you don’t drown, or so they don’t send a storm to kill you. There are some like the Jewish ones.