Edward T. Hall: The Great Grandfather of NLP

Much of the programming we use to create change through NLP techniques is the result of cultural programming1. Everything we’ve trained ourselves to do—and what we want to change (habits, problems, unhelpful behaviors)—is often a byproduct of our cultural background, especially in cross-cultural communication. This applies not only between different American cultures (African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans, and Europeans), but also between managers and employees, men and women, or parents and children.

Intracultural Communication

Many people don’t realize that some approaches used in NLP to solve such problems originated from pioneering work in the field of intercultural communication (ICC). This field studies subjective experience within culture: on one hand, independent, and on the other, taking into account language differences.

Most people date the birth of ICC to the publication of Edward T. Hall’s The Silent Language in 1959. If Gregory Bateson was the paternal grandfather of NLP, and Milton Erickson perhaps the maternal, then Edward T. Hall is undoubtedly the great grandfather. In my opinion, Hall is one of the greatest anthropologists ever. He’s also a practical man: he writes accessible books and consults for government and business. This is likely because he enjoys working with people who interact, produce results, and influence the world. Clearly, he’s not one to rest on academic laurels.

While I believe it’s always useful to know someone’s background (“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”2), my main reason for writing about Hall is to share what I’ve learned from his genius about understanding and navigating cultures different from my own. I’d like to present some key ideas for your enjoyment and admiration, along with examples of how I’ve benefited from them during the eight years I’ve lived in Europe.

Edward T. Hall as an Early NLPer

In The Silent Language, Hall wrote: “Experience is what a person projects onto the outside world as he receives it in his culturally conditioned form.” If NLP were based on a single presupposition, it would likely be this: the study of subjective experience begins with how we sort, select, and create our personal realities.

“The analogy with music is very useful in understanding culture,” Hall later said. “Musical measures can be compared to the technical description of culture… In both cases, the system of notation allows people to talk about what they do. I want to emphasize that these are laws governing patterns: laws of order, selection, and congruence.” Here, Hall could be talking about metaprograms.

“Like talented composers, some people are more gifted in life than others. They truly influence those around them, but the process stops there because there’s no technical way to describe, no terminology for their mostly unconscious actions. Someday in the distant future, when culture is more fully explored, an equivalent of a musical score will be created, one that can be learned and will be unique for each type of man and woman, for different activities, relationships, times, places, work, and play. We see people who are successful and happy today, who have satisfying and productive work. What sets their patterns apart from those whose lives are less successful? We need tools to make life less random and more enjoyable3.”

Clearly, Hall is talking about modeling. “Man is a model-building organism,” Hall wrote 16 years later, the same year Bandler and Grinder named NLP. “Grammars and writing systems are models of language… Myths, philosophical systems, and science represent different types of models of what social scientists call cognitive systems. The purpose of a model is to enable the user to better cope with the complexities of life. By using models, we see and explore how something is structured and can predict how things will go in the future. People closely identify with their models, which then become the basis for behavior. People have fought and died for different models of being4.”

Edward T. Hall earned his PhD from Columbia University in 1942. He conducted fieldwork with the Navajo, Hopi, Hispanic Americans, Europeans, and communities in the Middle and Far East. In the 1950s, he led training programs for the State Department, teaching technical and managerial staff working abroad how to communicate successfully across cultural boundaries. He taught at the University of Denver, Bennington College, the Washington School of Psychiatry, Harvard Business School, Illinois Institute of Technology, Northwestern University, and more. He currently lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and teaches widely in America, Europe, and Japan.

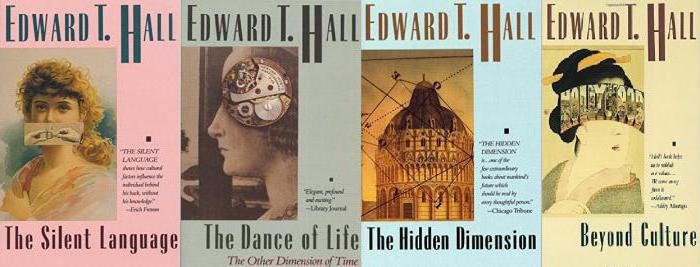

In The Silent Language, you can find the seeds of all the major themes Hall later developed. The field of intercultural communication began with this book. Hall’s genius is immeasurable. On the first page, he discusses two topics: time and space. Later, he would dedicate a separate book to each: The Dance of Life (1983) and The Hidden Dimension (1966).

Monochronic and Polychronic Time

Let’s start with time. Hall first distinguished between what he called monochronic and polychronic time. “M-time is one-thing-at-a-time, following a linear form so familiar in the West… a natural consequence of the Industrial Revolution. Monochronic cultures emphasize the importance of schedules—around the precision of meeting times and agreements, a special code of conduct is developed.”

“Polychronic cultures are the opposite: human relationships and interaction are valued above rigid schedules and planned meetings. Many things can happen at once (because many people are involved), and often things don’t go as planned… P-time is polychronic, meaning many things at once. P-time is common in Mediterranean and colonial Iberian-Indian cultures.”

Americans are usually monochronic, while the French, for example, are mostly polychronic. So what happens when I, an American living in France, enter a French office? I arrive exactly on time. The French manager talks on the phone during our meeting. Family members drop in. Subordinates ask questions. We leave the office for lunch. He invites several friends to join us. All this seems truly disorganized to me. For the French, it’s no problem. They’re used to doing many things at once.

A French colleague comes to my meeting. He’s late. I spend some time in small talk to build rapport, then move to the agenda. First, we discuss what we want, need, and expect; second, we negotiate the deal; third, we sign the contract. Finally, we spend a bit more time in pleasant conversation. My French colleague thinks this Van Der Horst is demanding and a pedantic bore!

In terms of our experience, these two cultural models of time can be represented by what we in NLP call “Through Time”—a monochronic timeline, and “In Time”—polychronic. If these definitions hold, they could be a potential contribution of NLP to identifying, understanding, and changing cultural misunderstandings5.

High-Context and Low-Context Cultures

The two time orientations above tend to produce two other important cultural phenomena: the difference between high-context and low-context cultures. “These terms describe the fact that when people communicate, they take for granted how much the listener knows about the subject. In low-context communication, the listener knows very little and needs to be told almost everything. In high-context communication, the listener is already ‘contextualized’ and doesn’t need much background information6.”

For example, American contracts are often ten times longer than French ones. Americans like lots of content, while the French don’t care as much if the content of the agreement is clear.

Remember: the French think, “If it’s a great idea, it should work”; Americans think, “If it works, it must be a great idea.” French culture is high-context; American culture is low/high-context.

Here’s another way to observe these differences. Jack, an American, is in France. He invites Marie, a Frenchwoman, to dinner and a show. At midnight, she serves coffee and cognac. Jack starts talking about what they have in common, looks meaningfully into her eyes, and tries to get close. Marie says, “Relax, Jack. You’re going to spend the night. Don’t fuss.” Jack thinks he’s a great Casanova, not realizing the context is already set, and the content—whether they’ll sleep together—will be decided as things unfold.

Jules, a Frenchman, is in America. The same scene, but with Mary, an American. Right after coffee and cognac, Jules makes a move. Mary is horrified. Jules doesn’t understand. He’s just received all the contextual markers of seduction. He doesn’t know Mary expects more content before starting a romance. She wants to know what they have in common, discuss their relationship, share personal details, exchange medical records, and only then move to romantic content.

Mike Tyson would never have been accused of rape in France. Under French law, the context of the situation determines what will happen. I know this sounds crazy, and I don’t condone violence. I’m just sharing what many of my French friends (including several lawyers) have told me. The idea of context is so important in France that if a woman enters a man’s hotel room at 3 a.m., a French jury will assume she’s already consented to sex. The context of numerous French court cases explains why “crimes of passion” receive such light sentences.

“The Japanese, Arabs, and Mediterranean peoples, where there’s an extensive information network among family, friends, colleagues, and clients involved in close personal relationships, are high-context,” Hall wrote with his wife Mildred Reed Hall in Understanding Cultural Differences (1990). “As a result, for most normal interactions in daily life, they don’t require or expect extensive background information. This is because they constantly maintain awareness of everything concerning people important to them.”

“Low-context people, including Americans, Germans, Swiss, Scandinavians, and other Northern Europeans, compartmentalize personal relationships, work, and many aspects of daily life. So every time they communicate, they need detailed background information. The French are much higher on the context scale than Germans or Americans. This difference can significantly affect any situation and relationship between people from these two opposite traditions7.”

The Hidden Dimensions of Space

The Hidden Dimension (1966) is Hall’s study of the cultural phenomenon of space, including invisible territorial boundaries, personal space, and multisensory (VAKOG!) perception of space (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, tactile, and olfactory senses), as well as distinctions rarely discussed in NLP. Here are some key ideas:

- Territoriality: “Americans tend to call certain spaces ‘theirs’: a cook calls the kitchen his, a child thinks the same about their bedroom. In Germany, this sense of ownership extends to everything they own. If someone touches a German’s car, it’s almost as if they touched the German himself.”

- Cultural orientation to sensory modalities: “High-context people don’t filter visitors but live successfully being open to interruptions and in tune with their surroundings. So, when you’re in a French or Italian city, you’re periodically overwhelmed by noise.”

- Personal space: “Around each person is an invisible spatial sphere (bubble) that expands or contracts depending on relationships, emotional state, culture, and the activity at hand. Some people are allowed a bit deeper into personal space, and only for short periods… In Northern Europe, this sphere is quite large, and people keep their distance. In Southern France, Italy, Greece, and Spain, these bubbles get smaller and smaller.”

These observations about personal space helped clarify something that bothered me for a long time in France. When I did my own research, I found that personal space is the area you must warn someone about and take action if they invade it. There’s also intimate space—a distance where intrusion is seen as invading one’s private life.

For Americans, personal space starts at about two outstretched arms. For the French—though it varies by region—it’s about one arm’s length. That’s the start of the intimate zone for Americans. For the French, the intimate zone starts at the elbow, or even closer.

I felt claustrophobic in French bathrooms for years. They’re very narrow: the walls touch your elbows, while in American bathrooms you can stretch your arms in any direction. Reading Hall, I realized French bathrooms invaded my intimate space, and suddenly I no longer needed to use V/K dissociation every time I wanted to use the restroom. I can just smile and say, “Ah, this little French room did it again.”

Another important point in Hall’s work, which I think can help NLP practitioners, is the concept of action chains. An action chain is “a term borrowed from animal behavior to describe internal processes where one action leads to another as a unified pattern. Courtship is a complex example. Setting up a date or inviting someone to dinner is another8.”

One of my favorite examples is from Paul Watzlawick during World War II. Both the English and Americans at the time called the other culture “overly sexual.” This is a rare cross-cultural conflict. Usually, misunderstandings are polarized: one culture is hot, the other cold. Watzlawick explains this in terms of action chains.

In both English and American cultures, there are, say, 20 separate steps in the courtship ritual: from the first hello to going to bed together. One step in both cultures is “kissing on the lips.” In America, this is step 3, necessary to establish intimacy. In England, it’s about step 18, almost the last thing before sex.

Imagine an American soldier on a date with an English girl. To move things along, he kisses her on the lips (like in Hollywood movies). The girl now faces a tough choice: she thinks the guy is obsessed with sex; plus, they barely know each other, and she’s been cheated out of 15 steps. So she might leave immediately. In this case, the Yank says, “She’s obviously hypersexual and hysterical: all I did was kiss her on the lips.” Her other choice is to start preparing for bed. The guy broke her action chain, so she’s one or two steps from the main event. If she acts this way, the Yank says, “She’s obviously hypersexual! She took off her clothes, and all I did was kiss her on the lips.”

The Case of the Naive Yank and the Arrogant Frog

Familiarity with Hall’s work can help you understand, forgive, and maybe even appreciate what’s invisible, transparent, and unexplored in cross-cultural conflicts. Take the case of a French marketing director I met at a party in suburban Paris. He complained that Americans are naive and childishly direct. Of course, I asked how he came to that conclusion.

He had worked in America on assignment. At the end of his first week, a colleague invited him to dinner. Later, his car broke down. He called the American and asked for a ride, but the American refused. “That’s how you know,” he said, “they’re friendly at first, but don’t maintain long-term friendships.” I’d heard this before. First, I tried to build rapport. I said, “I know that here in France, inviting someone to dinner is a deeply personal event, signifying a high degree of social recognition. In America, it’s often the same, but there are nuances.”

I started thinking about the differences between monochronic and polychronic cultures, high- and low-context, and action chains. My wife asked the Frenchman, “What did you do after that dinner?” “Nothing special,” he replied, “I brought flowers, we had dinner at his home.” I asked, “How much time passed between the dinner and the car trouble?” “Three months,” he said. I asked again, “If you were in France, would you invite someone you just met to your home for dinner?” “No, of course not,” he replied (I was already familiar with this action chain). First, you have coffee together, then go to a bar, then have lunch at a bistro, and then maybe dinner at a restaurant. After that, you decide if you want to invite them home. How long does this process take? Three to six weeks.”

“So you check the person out before inviting them home?” “Of course,” the Frenchman replied. “Well, Americans do the same,” I said, “but they test you after the dinner.” I explained that if you don’t send a thank-you note or call the next day, you’re considered rude. Also, if you don’t keep in touch by phone, letter, fax, or in person at least once a week, after three to six weeks the American will think you’ve ended the relationship. I continued, “I’m sorry, monsieur, but you didn’t pass the test.”

In France, however, years can pass after a dinner at someone’s home, but the relationship remains. That event, carefully considered in advance, is so special to the French that it takes very little to maintain the relationship. You can also begin to understand why, at first glance, the French often think Americans are excessive in their feelings, like children, and why Americans think the French are arrogant—if you think in terms of action chains.

The criteria of “maintaining contact” and “respectful behavior” are important in both cultures. However, in the US, you become attractive at the start of the action chain. So, if you care about making a good impression, here’s what to do behaviorally when meeting someone for the first time: smile and say nice things. Then decide how much you respect the person, especially in America, where there isn’t the same distance based on social status as in France. North Americans expect everyone to be roughly equal. Not so in France. Here, distance is maintained based on power and social class. (Would their national motto be “Wealth, Equality, Brotherhood” if it were truly their top value?) Here, respect is the first criterion to establish in social interaction. So, if you respect someone and are respected, what do you do behaviorally? You judge, evaluate, determine the other’s social class, then mirror the actions that will earn you respect in your home culture. Laughter, smiles, and pleasant conversation come later in your action chain, after you’ve established mutual respect.

All of Edward T. Hall’s works bear the mark of his genius. I recommend reading them all, in the order they were published, if you want deep insights into the scientific roots of NLP and how to master cross-cultural communication. If you only have time for one, start with Beyond Culture, an excellent overview of his work. It has four types of indexes: authors, subjects, topics, and “Ideas and Techniques of Transcendence.” The last section reads like poetry.

“A person cannot understand himself or the forces shaping his life through self-analysis alone, without understanding culture.”

“Cultures will not change until all people change. There are neurobiological, political, economic, historical, and cultural reasons for this.”

“Culture is a dictatorship if it is not understood and explored.”

“It is not man who must be synchronized with culture or adapted to it, but culture grows from synchronization with man. When this doesn’t happen, people go mad and don’t even notice.”

“To avoid madness, people must learn to go beyond culture and adapt it to the era and their biological organism.”

“To do this, since self-examination tells you nothing, a person needs experience with other cultures. In other words, to survive, all cultures need each other.”

Edward T. Hall’s Bibliography

- The Silent Language, New York: Doubleday, 1959

- The Hidden Dimension, New York: Doubleday, 1966

- Beyond Culture, New York: Doubleday, 1976

- The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time, New York: Doubleday, 1983

- Hidden Differences: Studies in International Communication, Hamburg: Grunder & Jahr, 1983, 1984, 1985

- Hidden Differences: Doing Business with the Japanese, Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1987

- Understanding Cultural Differences: Germans, French and Americans, Yarmouth: Intercultural Press, 1990

Most of these publications can be ordered through Intercultural Press:

Intercultural Press, PO Box 700, Yarmouth, ME 04096.

Bryan Van Der Horst has been a professional coach for 15 years. For the past 8 years, he has lived and worked in Paris as director of Repere. Previously, he was a consultant at the Stanford Research Institute in the Strategic Environment Group, in the Values and Lifestyles program, and was director of the NLP Center for Advanced Studies in San Francisco. He has worked in journalism as an editor for New Realities, Practical Psychology, Playboy, and The Village Voice. He has also worked as an acquisitions editor for J.P. Tarcher Books and Houghton-Mifflin, and hosted a TV show in San Francisco. Before that, he spent 10 years in the entertainment industry as vice president of the Cannon Group and director of advertising and PR at Atlantic Records.

- Culture here is used as a technical term by social researchers, meaning systems for creating, distributing, storing, and processing information created by humans, distinguishing them from other life forms, including beliefs, morals, customs, habits, art, science, and traditions. Synonyms include “worldview,” “model of the world,” or “subjective reality.”

- George Santayana.

- This last paragraph was used as an epigraph for “The Emprint Method” and “Know How” by Cameron-Bandler, Gordon, and Lebeau.

- Edward T. Hall, “Beyond Culture,” 1976.

- See chapter two of “Time Line Therapy” by Tad James and Wyatt Woodsmall, 1988, where this hypothesis is discussed.

- Edward T. Hall and Mildred Reed Hall, “Understanding Cultural Differences,” 1990.

- Ibid.

- “Beyond Culture,” 1976.