The Power of Words Is Not a Metaphor: How the Words and Actions of Others Shape Our Brains

We humans are a social species: we live in groups, care for each other, and build civilizations. Our ability to cooperate has been the main adaptive advantage that allowed us to colonize nearly every natural environment and adapt to a wide range of climates better than any other living creature—except perhaps bacteria.

An essential part of our existence as a social species is that we influence each other’s allostasisⓘ—the ways our brains manage the bodily resources we use every day. Throughout your life, you affect the allostasis of others, often without even thinking about it, just as they affect yours. This has both benefits and drawbacks, as well as serious consequences.

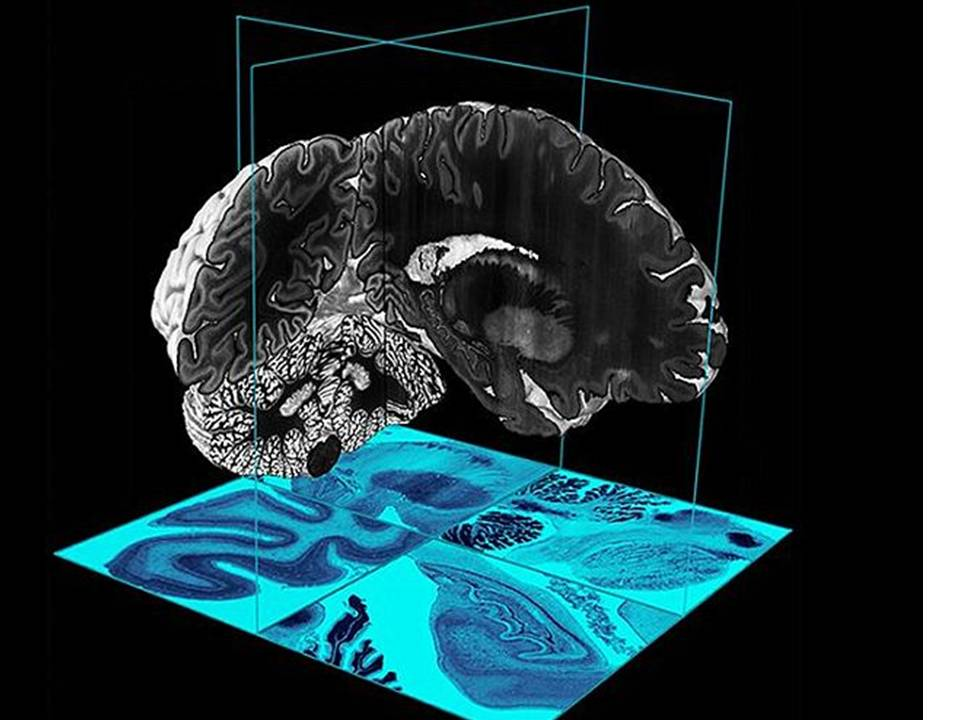

How do those around us influence our physiological state and the very structure of our brains? We know that the brain changes its structure after new experiences—a process called plasticity. Microscopic areas of neurons gradually change every day. Dendrites become more branched, and the neural connections between them become more efficient. Over time, the brain is tuned in certain ways through interactions with other people.

Some people’s brains are more attentive to others, some less so, but everyone has someone. Ultimately, your family, friends, neighbors, and even strangers contribute to the structure and function of your brain and help it maintain your body’s activity.

How We Regulate Each Other

This co-regulation has measurable effects. When you’re near someone you care about, your breathing can synchronize, as can your heartbeats—whether you’re having a casual conversation or a heated argument. This physical connection occurs between infants and parents, clients and therapists, and even among people attending yoga classes or singing in a choir together.

We can also change another person’s allostasis through our actions. Raising your voice or simply raising an eyebrow can affect what’s happening in someone else’s body, such as their heart rate or the chemicals released into their bloodstream. If a loved one is in pain, you can reduce their suffering just by holding their hand.

Our social nature gives us many advantages, including the fact that we live longer if we have close, supportive relationships. Studies show that if you and your partner feel truly close, caring, and responsive to each other’s needs, and enjoy life together, you’re less likely to get sick. If you already have a serious illness, like cancer or heart disease, you’re more likely to recover. These studies were done with married couples, but the results seem to apply to other close relationships, such as friendships or even pet owners.

On the flip side, being a social species has its downsides. We also get sick and die earlier when we constantly feel lonely—sometimes years earlier, according to scientific data. If others don’t help regulate our internal energy balance, we take on extra strain.

Have you ever felt like you lost a part of yourself after a breakup or the death of a loved one? That’s because you really did: you lost a source of support for your body’s systems.

Allostasis and Empathy

One remarkable feature of allostasis is its impact on empathy. When you empathize with others, your brain predicts what they will think, feel, and do. The more familiar you are with someone, the better your brain can forecast their problems. The whole process feels natural, as if you’re reading their mind.

But there’s a catch: if you don’t know someone well, it’s harder to empathize with them. You may need to learn more about them, which takes extra effort and can disrupt your internal balance, causing discomfort. This may be one reason why people sometimes fail—or don’t even want—to empathize with those who look different or believe different things. Our brains find it metabolically costly to engage with unpredictable matters.

It’s no surprise that people create so-called echo chambers, surrounding themselves with news and opinions that reinforce what they already believe. This reduces metabolic costs and the discomfort of learning something new. Unfortunately, it also lowers the chances of discovering something that could change your mind.

The Biological Power of Words

We also regulate each other with words—a kind word can calm you, like when a friend compliments you after a tough day. Hurtful words can flood your brain with stress hormones, draining your body’s resources.

The power of words over our biology can cross great distances. I can write “I love you” from the U.S. to my friend in Belgium, and even if she can’t hear my voice or see my face, I can change her heart rate, breathing, and metabolism. Or someone might send you a cryptic message like, “Is your door locked?”—which could trigger a negative reaction.

Moreover, your nervous system can be affected not just across distance, but through time. If you’ve ever found comfort in ancient texts like the Bible or Quran, you’ve received support for your body’s systems from people long gone. Books, videos, and podcasts can warm you or give you chills. These effects may be brief, but research shows we can all tune each other’s nervous systems with simple words, on a physical level.

Why do the words we encounter have such a strong effect on us? Because many areas of the brain that process language also control our bodies, including the main organs and systems that manage allostasis. The brain regions scientists call the “language network” also regulate our heart rate, control the flow of glucose into the bloodstream to feed our cells, and adjust the chemicals that support our immune system.

The power of words is not a metaphor; it’s built into the way our brain networks work. We see similar effects in other animals; for example, the neurons birds use for singing also control their bodily organs.

In this way, words are tools for regulating the human body. The words of others have a direct impact on your brain activity and bodily systems, and your words have the same effect on others. Whether you’re aware of this or not doesn’t matter—it’s just how we’re built.

Can Words Harm Your Health?

Does this mean words can harm your health? In small doses, hardly. When someone says something you don’t like, insults you, or even threatens your physical safety, you may feel terrible. At that moment, your allostasis is affected, but there’s no physical damage to your brain or body. Your heart may beat faster, your blood pressure may change, you may sweat, but then your body recovers, and your brain may even become more resilient to stress afterward.

Evolution has given us a nervous system that can handle temporary metabolic changes and even benefit from them. Occasional stress can be like exercise—short-term withdrawals from your body’s energy budget, followed by deposits, make us stronger and better.

But if we experience stress over and over without a chance to recover, the consequences can be much more serious. When we’re immersed in a boiling sea of stress and our energy system accumulates a growing deficit, the process becomes chronic. Its effects go far beyond just feeling unhappy in the moment.

Over time, anything that contributes to chronic stress can gradually damage the brain and cause physical illness. Stressors can include verbal aggression, social rejection, neglect, and countless other creative ways we, as social animals, torment each other.

It’s important to understand that the human brain probably doesn’t distinguish between sources of chronic stress. If your body’s resources are already depleted by life circumstances—such as physical illness, financial hardship, hormonal changes, lack of sleep, or exercise—your brain becomes more vulnerable to all kinds of stress. This includes the biological effects of words meant to intimidate, threaten, or torment you or those you care about.

When the body is constantly overloaded, even short-term stresses add up, including those you’d normally recover from. Imagine kids jumping on a bed: the bed can handle 10 kids, but the 11th breaks the frame.

Simply put, a long period of chronic stress can harm the human brain. Studies show that when you’re constantly exposed to verbal aggression, you’re more likely to get sick. Scientists don’t yet understand all the mechanisms, but we know it really happens.

Studies on verbal aggression have included average people from across the political spectrum—left, right, and center. If people insult you, their words may not affect your brain the first, second, or even twentieth time. But if you’re subjected to verbal aggression constantly for months, or live in an environment that strains all your systems and drains your resources, words really can physically injure your brain. Not because you’re weak or soft, but because you’re human.

Your nervous system is connected to the behavior of others, for better or worse. You can debate what these findings mean and whether they matter, but this is just how things are.

The Human Dilemma: Other People as Both Cure and Cause

This is the fundamental dilemma of being human: the best thing for your nervous system is another person, and the worst thing for your nervous system is also another person. Scientists are often asked to do research that’s useful in everyday life, and these findings about words, chronic stress, and illness are a perfect example. When people treat each other with basic respect, it has real biological benefits.

A realistic approach to our dilemma is to recognize that freedom always comes with responsibility. We are free to speak and act, but we are not free from the consequences of what we say and do. We may not care about these consequences or may not agree that they’re justified, but they come with costs that we all pay.

We pay the costs of increased healthcare for diseases like diabetes, cancer, depression, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s, all of which are worsened by chronic stress. We pay for ineffective government, where politicians spew venom at each other instead of having reasoned debates.

As our society makes decisions about healthcare, law, public policy, and education, we can ignore our socially dependent nervous system or take it seriously. Our biology isn’t going anywhere.

ⓘ Allostasis is the process by which the body achieves stability through physiological or behavioral change (Copstead & Banasik 2013).