The History of Psychiatry: Why We Stopped Exploring the Human Inner World

“Encountering mental illness is an inevitable doubt in the reality of our world.” Psychotherapist Maxim Chekmaryov discusses when the concept of mental normality emerged, the milestones psychiatry has experienced as a science—from isolating patients to showing empathy and attempting to understand their world and pain—the influence of Husserl, Freud, Jaspers, Foucault, and others, and how today, the study of the inner world has been replaced by schematization. What does this say about us and our society?

A few days ago, a teacher from an orphanage—most of whose wards are children with mental illnesses—asked me during a lecture: “What do you really think about inclusive education? Be honest.” As I thought about my answer, I realized it wasn’t just about education, but about psychiatry as a whole. I remember that it was mostly parents of “normal” children and teachers who wrote protests and attended rallies. Children with mental illnesses entered mainstream schools, which should be important for their adaptation, but is the school ready to accept them? Are “normal” children and their parents ready to give up the practice of isolating those they are used to fearing?

This question also made me reflect on why, for about a year now, I’ve started my psychiatry seminars for psychologists with the words:

“I’m going to talk to you about a psychiatry that doesn’t exist in reality, but that you should know about to help your patients.”

Why do I feel the need to sow doubt in established practices? Why do I want to plant seeds of opposition in their minds? The honest answer is bitter: the gap between the essence of medicine and the realities of the mental health system has become indecently obvious. People with mental disorders live among us, but is our society ready to accommodate them, and is the healthcare system ready to help? These questions rarely arise in cardiology, gastroenterology, or surgery. What makes psychiatry so different?

The Invisible Object of Suffering

First, the object of suffering—the psyche—is invisible and essentially immaterial. For a long time, this wasn’t a problem. If we look beyond medicine, healing the soul with the soul has existed as long as civilization itself. It’s closer to religion, philosophy, and education than to the natural sciences, because at its center is a person reflecting on their existence, discovering their soul and relationships with others, the world, and God, as Karl Rahner wrote. Mentorship, confession, and other spiritual practices exist in many cultures. Roger Walsh summarized them in his book “Essential Spirituality: The 7 Central Practices to Awaken Heart and Mind,” showing how spiritually oriented psychotherapy is possible for both modern people and our ancestors.

So far, we’re only talking about psychotherapeutic methods, not psychopathology. Yet every culture has a concept of mental illness. Different explanatory models formed around it, often marked by fear and awe of the unknown. Sometimes, the mentally ill were revered as saints, like the “holy fools” in Russia; sometimes, they were chained in prisons or monasteries, as in medieval Europe; sometimes, they were killed or exiled. The unknown breeds not only fear but also curiosity, so discussions about psychological and physical causes of mental disorders have existed as long as medicine itself. Hippocrates sought physical causes for mental disorders. Paracelsus identified a separate category in his famous classification of diseases related to strong emotions and thoughts. Avicenna noted that mental anguish and passions often set the stage for disorders. In traditional Eastern medicine, which is holistic, there was no division between physical and mental disorders at all.

However, doctors’ ideas alone weren’t enough to create a new medical discipline; there simply wasn’t enough opportunity to observe patients due to various social constraints. This changed during the Renaissance, when, as Michel Foucault noted, the clinic emerged, based on standardizing human nature. The concept of “normal” appeared as a statistical average, measured by social usefulness and adaptability. The mentally ill, unable to meet these criteria, were isolated. Even by the late 18th century, a typical psychiatric hospital in Europe was a prison with cells, chains, and shackles.

Psychiatry as a Science: Then and Now

Clinical psychiatry could only develop when it became possible to observe patients in relatively free conditions. This happened when French physician Philippe Pinel, director of the Paris “Bicêtre” clinic, convinced the leaders of the French Revolution to abolish chains and shackles, replacing prison cells with wards and police supervision with medical care. Medicine gained access to the patient’s inner world. Pinel’s idea of not restraining the mentally ill quickly spread across Europe, and many young, promising doctors entered psychiatric clinics. Their main tool was remarkable attentiveness to patients. S.S. Korsakov wrote:

“…Of all medical sciences, psychiatry brings us closest to philosophical questions. Self-knowledge and understanding the highest mental qualities of a person have always been among the deepest aspirations of thinking people, and psychiatry provides more material for this than any other branch of medicine.”

19th-century psychiatry was unique. It was woven from meticulous descriptions not only of clinical symptoms but also of patients’ experiences and life stories. Some doctors even studied symptoms in themselves. For example, Victor Kandinsky described pseudohallucinations by provoking them with morphine. Descriptions of patients’ mental states from that era read like literature. It’s no surprise that Husserl’s phenomenology was quickly adopted in psychiatric clinics, and existentialism began to develop there. By the late 19th century, thanks to Freud, it became clear that psychological intervention could treat mental disorders, and psychotherapy became a main method of help. Discussing the doctor-patient relationship, Freud began using the term “empathy,” previously introduced by Titchener. For Freud, empathy meant the ability to immerse oneself in the patient’s world, to feel with them, to see circumstances through their eyes.

The Golden Age: The Inner World at the Center

Psychiatry entered the 20th century with a developed understanding of mental illness, a deep and nuanced classification of disorders, and a desire to continue exploring the patient’s inner world. Karl Jaspers’ “General Psychopathology” is perhaps the most emblematic work of that period—a fundamental guide helping clinicians reconstruct the patient’s worldview, understand the impact of symptoms on life, and build therapeutic relationships. No clichés, no desire to reduce a person to a scheme. Around the same time, Martin Heidegger, at the invitation of Medard Boss, conducted the famous “Zollikon Seminars” for psychiatrists, while in the Soviet Union, the theory of nervism continued to develop, and Georgy Lang described hypertension as a psychosomatic disorder. Healing the soul with the soul gained the trust of the medical community.

I’ve tried to describe the astonishing development of psychiatry and related disciplines in a few paragraphs, but I must admit that we have lost that psychiatry.

The Shift: From Humanism to Biologism

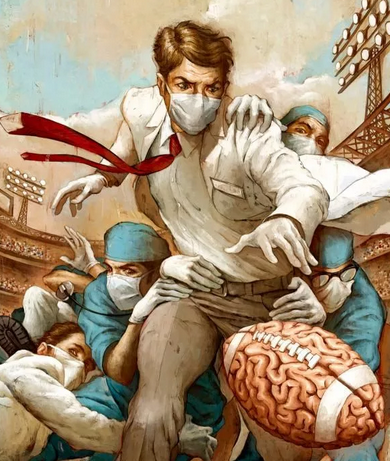

It didn’t take long for the 20th century to radically change psychiatry. Here’s one telling fact: in its entire history, the Nobel Committee has awarded only two psychiatrists the prize in medicine and physiology—Julius Wagner-Jauregg for treating neurosyphilis with malaria, and Egas Moniz for inventing lobotomy. The humanistic movement faded, and psychotherapy gave way to biological treatments.

Patients were no longer chained, but the invention of antipsychotics in the 1950s enabled pharmacological restraint. We returned to the problems of the Renaissance era. The person was no longer the focus of the doctor’s interest; instead, medicine focused on the disease and its mechanisms—bioelectrical, biochemical, genetic. The person suffering from a mental disorder became an inconvenience to science and society, so they were either isolated for severe disorders or ignored for milder ones.

Psychiatry’s complex history is due to how knowledge about mental disorders is formed. As long as it was the domain of passionate researchers and caring doctors, it had the power and means to help. Once it became a system, the magic was lost, the patient was devalued, and became marginalized by the very system meant to help, which went hand in hand with isolation.

Medical disciplines rarely developed this way. Usually, increased access to care improved quality of life. But psychiatry’s development resembled the growth of a religious movement, where, after the founder’s death, institutionalization and political motives take over.

This isn’t surprising—helping the mentally ill is directly tied to the specialist’s attitude. Faith is essential: faith in the person, their resources, the presence of a healthy part even in severe disorders. As soon as a conveyor-belt approach appears, doctor and patient are divided by standardized categories of “normality.” In this sense, both psychiatry and psychotherapy are unscientific. Strictly speaking, medicine is also unscientific when we try to study a living person in the process of being. We must engage with their suffering, life story, and many social factors, from education level to family structure. Pure experiments are only possible in test tubes. The psyche, as the most common definition says, is a subjective reflection of the external and internal world. Mental disorders also exist primarily subjectively. Today, we can observe changes in brain function, but that tells us nothing about what our patient actually feels, thinks, or experiences. We won’t know until we ask, until we make contact.

At the boundary between two people lies the psychiatrist’s clinical thinking. If there’s no contact, if we deny the very possibility of finding meaning in psychopathology, we can’t help. That’s what’s happening now. The most common disease classifications—ICD-10 and DSM-V—focus on behavior and external manifestations. Doctors can only guess about the inner world. The drive to become a science of the material substrate of the psyche has rendered psychology and psychiatry sterile, even though their subject is made of the ideal.

Antipsychiatry and the Return to the Inner World

It’s no surprise that antipsychiatry movements grew in the mid-20th century. Notably, both antipsychiatry and humanistic psychiatry, as well as classical psychiatry, draw on the same philosophical sources—phenomenology, existentialism, psychoanalysis, and sometimes even Marxism. The goal is familiar: to reconstruct the patient’s inner world, to understand the meaning and function of their symptoms. In “The Divided Self,” R.D. Laing gives many examples of the suffering person behind the symptom. The patient gains a voice; their abnormality isn’t seen as a deficiency leading to loss of rights. Laing often notes that mental illness is often the prerogative of “normal” people, who cause suffering—wage wars, invent nuclear weapons, support social injustice. He gradually proves that the supposed danger of the mentally ill is exaggerated. We turn away from abnormality because it’s painful to see; it undermines the foundations of our world. It takes courage to be near a suffering person and to empathize.

Carl Rogers, in dialogue with Paul Tillich, once said he saw no need to correct his client during psychotherapy; it was enough to remove obstacles to the client’s human nature and natural drive for healing. For that, you simply need to be present. Many humanistic psychotherapists and psychiatrists argue that the point of clinical diagnosis is not to label, but to determine potential and understand the state. We learn to see the patient in a dynamic perspective. A dynamic perspective gives hope. Antipsychiatry is even ready to abandon the idea of “curing” a person with a mental disorder. This sounds extreme, but it makes sense. Letting go of the passionate desire to return the mentally ill to “normal” only benefits the psychiatric system. Chronic mental disorders require the same approach that somatic medicine has developed for chronic conditions. Phrases like “diabetes or asthma aren’t diseases, but ways of life” are just as true for schizophrenia. Chronic illness stays with a person for life, and our job is to make that life as high-quality as possible—preventing relapses, developing educational programs, providing career guidance, teaching patients to control their symptoms and use different treatments consciously. Modern psychiatry should offer psychological and medical support in natural, not isolated, living conditions, with the most patient-friendly legal system possible.

For now, things are different—the help system resembles supervision, albeit relatively mild, and having a diagnosis means exaggerated loss of rights, limiting social adaptation. In healthcare, the diagnosis is more important than the patient’s current state, even though that’s what determines quality of life. I’ve often seen children with autism or childhood schizophrenia taught using programs meant for intellectual disability. Even a layperson can see these disorders are very different, and a specialist knows that every child with intellectual disability has unique features. A system that thinks in terms of “normal-pathology” and “diagnosis-correction” deprives itself of the chance to approach patients individually, and people around are often not ready to see a sick child as sick. To them, the child just behaves abnormally and disrupts their sense of order. Jung wrote about society’s tendency to focus on the “average person.” The mentally ill can never be average.

It turns out that the most innovative way to organize psychiatric care is not new, but a well-forgotten old one. Classical psychiatry, ready to be an interdisciplinary field—integrating medicine, education, psychology, philosophy, social work, and sometimes even religion—can become the core of a new system, where care is built for each patient de novo. We’ll have to return to a psychotherapeutic focus and diagnostics aimed at studying the inner world, not just external symptoms. We can’t do without mass education of the “normal” world to overcome their aggression and fear toward the mentally ill. Otherwise, we’ll just keep isolating people with mental disorders so they don’t remind us of our own potential for madness, because encountering mental illness is an inevitable doubt in the reality of our world.

The psychiatrist played by Marlon Brando in the wonderful film “Don Juan DeMarco” gradually realizes that his patient’s world is much more interesting than his own limited one. Meeting someone mentally different can expand our ideas of what a person can be—if humanity is more important to us than the illusion of social and mental stability. In seminars for psychologists, I ask participants to recall their own “psychopathological” experiences—states and phenomena that frightened or confused them—and they always find some. Deep down, we all have some experience of psychopathology. Psychiatry is closer than it seems, and we shouldn’t forget that.