How Does the Brain Suppress Willpower?

Emotions helped our ancestors make decisions in situations with limited information. Emotions are an ancient evolutionary development. They allowed our distant ancestors, who lacked complex analytical systems, to make quick decisions when information was scarce. If you were a small monkey, your main goal in life was to grow up and reproduce before the first passing tiger decided you’d make a tasty snack. Decisions had to be made fast: there was no time to call a meeting or brainstorm whether to eat all the berries from a bush or save some for tomorrow. But you didn’t need help from colleagues—once you spotted some delicious, sweet berries, there was no question: pick and eat them immediately. Emotions reliably guided animals on what to do, long before their slower, rational thinking could reach the same conclusion.

This fast-acting emotional system helped us survive for millions of years precisely because it’s tuned to make the “right” decisions from a biological perspective. Food is good—eat it right away, and the sweeter and fattier, the better. Sex is very good—so do it as often as possible and with as many partners as you can (especially if you’re male). Tigers are bad—run away, and do it quickly, rather than pondering whether the tiger could be a business partner under different circumstances. Rest, when nothing is chasing you, is wonderful—so if you have a chance to be lazy, you should take it. It all makes perfect sense.

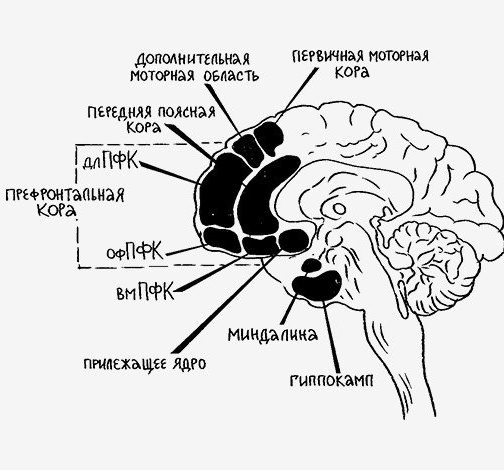

Supermarkets, fast food, drugs, paid sex, and video games are all recent inventions, and our emotional system hasn’t yet learned to respond to them appropriately. Maybe in a few million years, our descendants will instantly feel disgust at the sight of candy bars or run away when they see a social media page, but for now, our brains still consider what we call “temptations” to be good by default. These hardwired settings make it difficult for us to exercise willpower. Fortunately, advanced mammals, including humans, have developed what’s called the neocortex—the “intellectual” part of the brain. Thanks to it, we think, speak, perceive ourselves as individuals, create, analyze, calculate, plan, and invent. Somewhere deep in the brain, at the intersection of its new and old regions, lies our ability to rein in impulses (with varying success), subordinating ancient, simple desires to complex modern goals.

Emotions Are Generated in the Limbic System

In Christopher Nolan’s film “Inception,” the characters travel through the “limbo” of their target’s mind—a term used in the movie to describe the deepest level of sleep, the “pure subconscious.” Thanks to Nolan, the unfamiliar term entered popular usage, even among people far removed from neuroscience. In the real brain, the limbic system is indeed crucial—though it has nothing to do with Nolan’s “pure subconscious.” In Latin, limbus means “border” or “edge,” and in the brain, it’s the border between the neocortex and older structures (more precisely, between the neocortex and the brainstem). This area looks like a ring with branches, and in anatomy textbooks, it’s called the limbic system.

This is where all our emotions “reside”—from anger and rage to joy and bliss. Mother rats whose limbic systems were intentionally damaged completely lost interest in their pups, stopped feeding them despite their desperate squeaks, and acted as if the pups were inanimate objects. Even more impressive than destroying the limbic system is overstimulating it. In 1954, American physiologists James Olds and Peter Milner decided to see what would happen if they stimulated certain areas of rats’ brains with electricity. They implanted electrodes in the rats’ heads and activated them when the animal entered a specific corner of the cage. At the time, the brain’s fine anatomy was poorly understood, and the researchers, without realizing it, hit the very “heart” of the limbic system—the famous pleasure center. To their surprise, after a few shocks, the rats began to seek out the corner instead of avoiding it. Realizing that stimulation of this area brought pleasure, the researchers connected the electrodes to a lever so the rats could activate the current themselves. Once they figured out the mechanism, the rats stopped eating and drinking, spending all day pressing the lever—some managed to do it up to 700 times an hour!

Emotions Instantly Change Our Physical State

Olds and Milner’s experiments clearly show that emotions can drastically change behavior. Moreover, the limbic system directly regulates our physical state: its signals (via the hypothalamus) trigger a whole set of reactions that either relax the body or, conversely, put it on high alert (in English, this is called the “fight or flight” response).

When relaxed, the body is ready for all sorts of pleasures: it increases saliva production, boosts intestinal activity and digestive juices for a good meal, lowers blood pressure and reduces lung ventilation for proper rest, and stimulates erection for enjoyable sex. In a state of anxiety, functions unrelated to fighting or fleeing are ruthlessly suppressed, and all resources go to the muscles, lungs, and circulatory system. A special role in activating the “fight or flight” state belongs to the amygdala—a small area inside the temporal lobe (each hemisphere has its own amygdala). The amygdala can receive and analyze sensory information even before the cerebral cortex processes it. In other words, you haven’t yet realized that a tiger has jumped out of the bushes, but you’re already running in the opposite direction, amazed at how fast you can move.

To launch all these complex reactions and either relax or energize the body, the hypothalamus sends commands to parts of the nervous system that directly control internal organs. The part responsible for relaxation and recovery is called the parasympathetic nervous system, while the part controlling the “fight or flight” state is the sympathetic nervous system. Even from this simplified description, it’s clear how much the limbic system can change the body’s functioning and how much its influence was underestimated by proponents of the “pure reason” theory. How can you control your desire to order pizza for dinner when your mouth is already watering, your stomach is growling, and a pleasant warmth is spreading through your body? Rational thinking may warn you that the scale will soon show something unpleasant, but its advice comes too late and doesn’t evoke nearly as strong a response. The limbic system is powerful and demanding: we literally feel its commands physically, because their purpose is nothing less than to save our lives and pass our genes on to the next generation. We are programmed to automatically react to the most important survival stimuli, and this program cannot be canceled.

The limbic system is closely tied to our ability for self-control. While it may seem that, for evolutionary reasons, it prevents us from being strong-willed and determined, in reality, it’s a powerful machine that can be used to strengthen willpower. But to understand how, we first need to see how the advanced neocortex tries to restrain our unruly impulses.

We Are Our Neocortex

From an evolutionary perspective, the neocortex is a relatively recent development. Mammals acquired this extra “blanket” of several layers of neurons covering the “old” brain about 280 million years ago, or possibly even later. In early mammals, the neocortex was a tiny outgrowth of older brain regions, covering just 1–5 cm² and offering no major advantages. In humans, the neocortex has grown to an impressive 800 cm² and makes up 80% of all gray matter. In many ways, Homo sapiens is its neocortex: this part of the brain is responsible for consciousness, thinking, and everything else that sets us apart from other animals. Scientists divide the neocortex into many parts based on their structure and assigned tasks, though, as mentioned above, the specialization of each part can vary somewhat, but not too much.

The Anterior Cingulate Cortex Helps Us Resolve Conflicts Between Actions and Goals

The main area essential for controlling impulses is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). It’s part of the so-called reward system (which reinforces behaviors beneficial for survival) and provides emotional coloring to our actions. Thanks to this area, we even realize that something needs to be restrained. On MRI scans, the ACC lights up when a person faces a conflict—for example, when trying to name the color of letters in the Stroop test (where the word “red” might be written in blue letters, and you have to suppress the urge to read the word instead of naming the color).

The ACC also activates in other situations where the brain needs to overcome a contradiction—such as between true thoughts and social norms. A typical example is confronting racial stereotypes. The anterior cingulate cortex acts as a bodyguard, vigilantly monitoring for conflicts.

Research has shown that the ACC automatically “turns on” when a conflict arises (like the urge to smoke in someone trying to quit), but the degree of activation varies from person to person. In other words, due to the brain’s “design,” some people are better at filtering out conflicts between immediate and long-term goals than others, and this process happens unconsciously. If there’s no conflict, the brain sees no reason to suppress impulses—so the limbic system gets to grab another candy or say something inappropriate, even if the person consciously believes sugar is harmful or that prejudice has no place in modern society.

You Can Train Your ACC to Do Its Job Better

Here’s the not-so-great news: people who aren’t lucky with their ACC’s “wiring” will regularly fall victim to their passions, even if they don’t want to. But it’s not all bad: several experiments have shown that strong internal motivation to resist the limbic system’s tricks helps people control their impulses better. In other words, if you regularly remind yourself that excess weight is dangerous to your health, or that it’s shameful for a civilized person to consider any group inferior, sooner or later your efforts will pay off, and you’ll learn to notice and stop automatic reactions. Importantly, this kind of training helps you recognize the conflict, but it won’t help you stop a bad action once it’s started—other systems are responsible for that.

But you can only train your ACC using internal motivation. If you’re just following external prompts, you might be able to restrain yourself in a specific situation, but as soon as the “supervisor” is gone, you’ll revert to old habits. That’s why so many people work out diligently with a trainer at the gym but can’t do the same exercises on their own, even if they know the technique perfectly.