What Is the Hawthorne Effect?

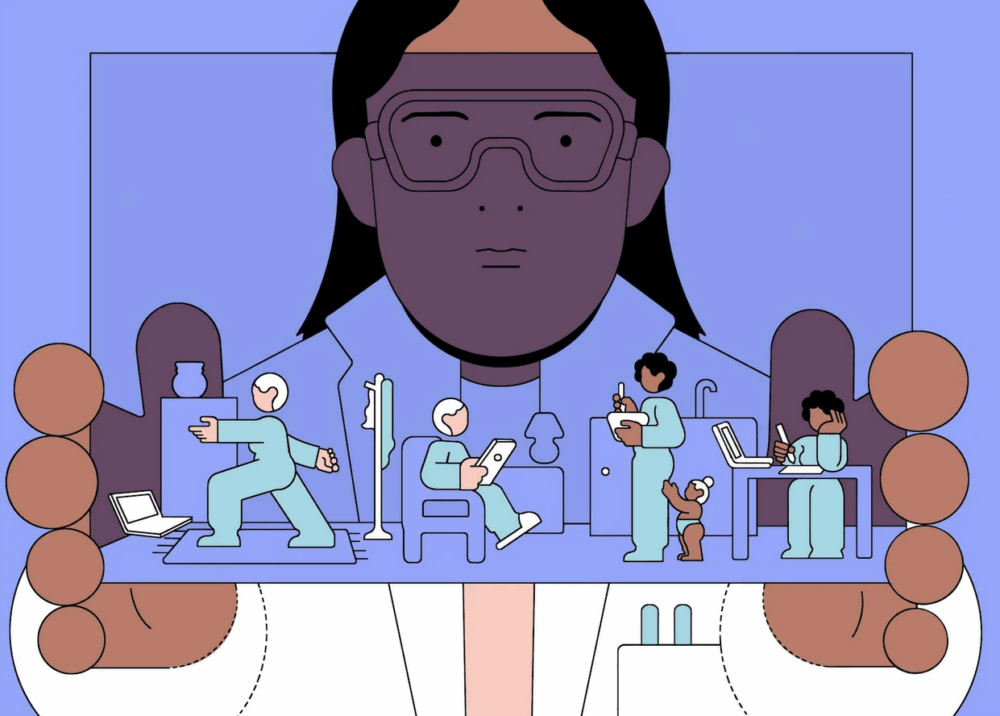

Most cognitive biases affect how people interpret events and make decisions. However, there is a more specific area where biases can have an impact: they can influence a participant during the course of an experiment itself. In this post about cognitive biases, we’ll explore the “Hawthorne Effect,” a phenomenon observed in psychological and sociological research, and discuss how it can distort scientific results.

The Role of Cognitive Biases in Social Science

The aspect of life most affected by cognitive biases is science—specifically, the social sciences, which study how people think and behave. Cognitive biases can influence both the experimenter and the research participants, but they always affect the outcome. The Hawthorne Effect describes a situation where a research participant, knowing they are being observed, deviates from their usual behavior for various reasons.

The Origin of the Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect (sometimes called the “observer effect,” though we’ll avoid that term to prevent confusion with the “bystander effect”) is named after the Hawthorne Works, a factory owned by the American company Western Electric, where it was first discovered.

The story dates back to the 1920s. The company’s management noticed a decline in productivity at the factory and invited psychologist Elton Mayo from Harvard University to investigate. With management’s approval, Mayo decided to conduct an experiment: he wanted to see how changes in workplace lighting would affect the productivity of female workers assembling electrical relays.

Mayo observed that increasing the lighting improved productivity, but when the lighting was reduced to its original level, productivity did not drop back down; it decreased, but only slightly.

Over the next five years, Mayo conducted several more experiments: he seated workers in small groups in separate rooms or changed the length and frequency of their breaks. The results were similar: manipulations intended to boost productivity had some effect, and reversing those changes did not completely eliminate the effect.

Mayo concluded that it wasn’t the independent variables (like lighting or break times) that influenced productivity, but rather a secondary variable: the workers’ awareness that they were participating in an experiment.

Reevaluating the Hawthorne Effect

It’s important to note that Mayo’s data may have been misinterpreted. Researchers who re-examined the data in 1992 found that the original Hawthorne Effect was not actually observed (at least, it couldn’t be proven numerically), and if it did exist (Mayo may have relied on qualitative rather than quantitative interpretation), its impact was very small.

However, these critics do not doubt the existence of the Hawthorne Effect itself. Other studies conducted years after the original experiment have confirmed the effect, and not just in the context of workplace productivity.

Why Does the Hawthorne Effect Occur?

Interestingly, the cognitive bias associated with the Hawthorne Effect doesn’t arise from a person’s pre-existing beliefs or faulty thinking, but rather from external factors: the presence of an experimenter and the very fact that an experiment is taking place. Researchers after Mayo suggested that the effect may be caused not just by being observed, but by what that observation means to the participant.

For example, the productivity increase at the Hawthorne Works could have been due to workers believing the experiment was part of management’s policy to evaluate their work and potentially fire underperformers. In any case, the mere fact of participating in an experiment always influences people, even if only slightly.

Can the Hawthorne Effect Be Avoided?

Unlike other confounding variables in behavioral experiments, which can often be eliminated by choosing the right methodology (such as double-blind studies, where neither the experimenter nor the participants know exactly what is being studied), the Hawthorne Effect is not so easy to avoid.

It is possible (and even necessary) not to tell participants the true purpose of the study until it’s over, and to make it as difficult as possible for them to guess what’s happening (for example, by not recruiting people with a background in psychology for psychological experiments). But how can you convince someone that they’re not participating in an experiment at all?

First, there’s the ethical side. Most studies involve collecting personal information and using it later, which cannot be done without the participant’s consent. That’s why psychological and sociological research always involves bureaucracy (some for the participants, and often endless paperwork for the researchers themselves).

Second, it’s often simply impossible to mislead participants: they’re asked to perform certain tasks in the presence of an observer and to complete a series of surveys.

However, psychologists argue that using a control group can reduce the impact of the Hawthorne Effect. Of course, the control group will also be affected, but comparing the results of the control and experimental groups allows researchers to determine the size of the shared deviation and exclude it from the analysis.