The Third Man Argument: Plato, Aristotle, and the Question of Human Nature

Greek Philosophy and the Foundations of Western Thought

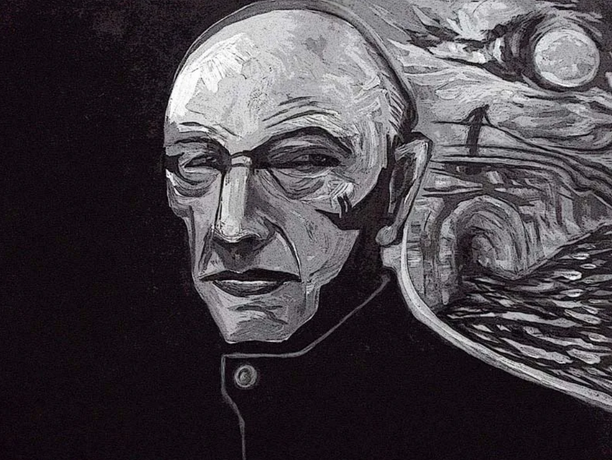

Ancient Greek culture, and philosophy in particular, laid the groundwork for what we now call European or Western self-awareness. The fundamental problems and paradoxes uncovered by the inquisitive Greeks during their endless debates remain unresolved and relevant—not only in the context of modern philosophical knowledge but often in various aspects of everyday life. For example, the opposition between the ideal and the material, rooted in the question of the eternal versus the changing (first posed by the pre-Socratics), is closely tied to the question: what is a human being? Are we merely shadows of eternal ideas, subservient to them, or living, thinking beings worthy of our own unique paths and the right to happiness? What are the consequences of choosing one idea over the other? And what is the “third man” in the philosophical debate between Plato and Aristotle? Philosopher Alexey Kornienko explores these questions.

Miracle or Curse?

The historical event that predetermined the birth of Western civilization is often called, following Ernest Renan, the “Greek miracle.” As with any miracle, its origins are unknown, but its consequences are clear. A group of Indo-European tribes, calling themselves Hellenes and everyone else barbarians, achieved the impossible: they pulled humanity from the grip of myth and pointed the way to the realm of reason. This event not only freed us from the illusions and prejudices of mythological thinking but also doomed us to endless doubts and contradictions inherent in rational consciousness. It’s as if those who called themselves philosophers and spoke on behalf of reason angered the gods, who, before leaving the mortal world, cast a final curse. Since then, philosophers, like children, can only argue and ask questions they cannot answer.

The modern Western person has long since grown up and even aged. Proudly claiming the legacy of antiquity and enjoying the benefits of democracy and science, the ancient “curse” still hangs over them. Old worldview conflicts flare up everywhere: in schools and universities, parliaments and churches, art galleries and scientific journals. And nowhere is there an answer to the eternal question: what is a human being? And how should we live?

Unable to atone for the sins of our ancestors, we can at least pay them respect by revisiting one of the most significant problems of ancient philosophy, embodied in the debate between Plato and Aristotle. This debate centers on the theory of ideas, with the so-called “third man” argument playing a key role—a concept whose fate, as we’ll see, is tied not only to the intellectual elite but also to the average Western citizen. Even if we can’t break the power of the ancient curse, we can at least clarify the origins of some persistent problems and questions.

Socrates and the Pre-Socratics

Plato’s theory of ideas emerged within an established philosophical tradition, attempting to answer questions posed by his predecessors—the pre-Socratics. As the name suggests, the pre-Socratics were thinkers who lived before Socrates. The slight condescension in the “pre-” is misleading, as the division of ancient philosophy into “before and after Socrates” is arbitrary, and the importance of pre-Socratic ideas is hard to overstate. Thanks to them, the mind, awakened from its mythic slumber, first recognized its freedom and turned its gaze to the mysteries of the world.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the human mind was idle in the world of myth. It performed complex engineering calculations for temples, tracked the stars, navigated the seas, and measured time by the sun. But human thought was always confined to utilitarian needs—whether for a good harvest or the soul’s immortality. The pre-Socratics broke with this paradigm. For them, the pursuit of knowledge became valuable in itself, and the selfless search for truth became the ideal of a virtuous life.

Thus, the human mind, rising above the mundane, saw the world as a cosmos—unified and beautiful, yet in need of explanation. Everything in it changed, grew, moved, was born and died, yet the world remained itself. To make sense of this paradox, the first philosophical concepts emerged. Heraclitus believed everything is in flux and only change is eternal. Parmenides, on the other hand, argued that change is an illusion; if we look at the world as a whole, it is eternal and unchanging. The pre-Socratics sought ways to reconcile the eternal and the changing: Democritus taught that the changing world consists of eternal, indivisible atoms; Empedocles saw all things as combinations of four elements; Anaxagoras believed everything is made of indestructible “seeds of all things.”

Behind these seemingly naive concepts lies the ancient mind’s attempt to reconcile the eternal with the temporal, the finite with the infinite—an attempt that always failed. This intellectual game might have continued indefinitely if not for Socrates, who, according to Diogenes Laertius, brought philosophy down from the heavens to the marketplace. Socrates turned the Greek mind from cosmological to ethical questions. In short, he was less interested in how the world works (which, he thought, only the gods could know) and more in what it means to be human. But this focus on humanity was short-lived; Socrates’ student Plato soon returned to the quest for ultimate truth about the world.

The Theory of Ideas and the “Second Man”

With this background, we approach the “third man,” who was born in Plato’s thought, though he entered under a false name. Plato, born Aristocles, was broad in both mind and shoulders—hence his nickname, meaning “broad” in Greek. Like many young Athenians of privilege, Plato fell under Socrates’ influence and witnessed his teacher’s execution for “corrupting the youth and inventing new gods.” This event left a deep mark on Plato’s life and thinking. From Socrates’ call to turn our gaze from the stars to humanity, Plato concluded that before trying to understand the world, we must first understand how humans perceive it.

It was already known before Plato that knowledge involves not just the senses but also a rational principle that organizes sensory data into images. The Pythagoreans, for example, taught that the soul “sets limits to the unlimited” and brings harmony to the chaos of sensation. But Plato was the first to notice that before the soul or mind can assemble sensory data into the image of a human, it must compare it to a model to confirm it is a human and not a monkey or a horse.

According to Plato, these archetypes or ideas (from the Greek idea—form) are hidden from physical sight and accessible only to the mind. Every day we see thousands of men and women, old and young, but we never see “the human.” The idea of a human has no specific age, gender, skin color, or eye shape, but is instantly recognizable. The idea of a human is eternal, never born or dying, existing in a world of ideas we only dimly remember. Plato’s theory of ideas is closely tied to his belief in the transmigration of souls, which he borrowed from Indian wisdom or Pythagorean mysteries. The soul is immortal and only temporarily inhabits a body. It once dwelled in the world of ideas but fell to earth due to its folly. Now, in the material world, it recognizes glimpses of eternal essences in finite things. A jug seems beautiful because we have seen true beauty before; we recognize a human because it partakes in the idea of humanity.

This theory, still bearing traces of mythological thinking, allowed Plato to elegantly solve the pre-Socratic problem of the eternal and the changing. All that is unchanging and eternal is placed in the ideal, supersensible world; all that is changing and mortal remains in the material world. It’s only a short step from seeing the material world as a shadow of the ideal to declaring it a realm of sin and suffering—a view adopted by many pagan and Christian followers of Plato. Thus, the unified and beautiful cosmos of the pre-Socratics splits in two, and humanity, once in harmony with itself and the world, meets its ideal double, or “second man.”

Aristotle’s Critique and the “Third Man” Argument

Like any major intellectual achievement, Plato’s teachings spread beyond his immediate followers and influenced many areas of ancient culture. The school he founded in the land dedicated to the mythical hero Academus lasted a thousand years until Emperor Justinian closed it in 529 AD. Many great philosophers, mathematicians, astronomers, and politicians emerged from the Academy, but none left as significant a mark as Aristotle. After twenty years in the Academy, Aristotle presented his teacher with a bill for wasted time. Absorbing all of Plato’s wisdom, Aristotle found flaws and gaps that Plato himself did not hide.

Aristotle’s main criticism targeted the theory of ideas, specifically the doctrine of “participation.” According to Aristotle, when Plato says all things participate in ideas and only through this participation do they exist, he explains nothing. The hardest question remains: how does this participation actually work? If, to know what a human is, we must always refer to the idea of a human, then we also need an idea of participation to connect the two. Moreover, if such an idea exists—what Aristotle calls the “third man”—then we would need yet another idea, a “fourth man,” to reconcile the third with the first and second, and so on ad infinitum.

Thus, the “third man” appears out of nowhere, challenging the primacy of the “second man” and reviving the “first.” Plato was aware of the “third man” problem; in his dialogue Parmenides, he discusses a similar issue, though there it concerns the idea of “greatness” rather than “human,” which doesn’t change the essence.

Aristotle’s innovation was not just in reproducing Plato’s reasoning but in offering an alternative to the theory of ideas. In Aristotle’s view, a human, like any being, is not a shadow of an eternal idea but a living, concrete individual, the result of four causes: formal, material, final, and efficient. In other words, a person’s existence is due to the conscious or unconscious actions of their parents (efficient cause), is born for a purpose (final cause), has a body (material cause), and belongs to a biological species (formal cause). The “form” or image that defines a human is not in a supersensible world, as Plato thought, but is realized in the body as it grows. Aristotle thus tries to overcome Plato’s dualism and solve the pre-Socratic problem of the eternal and the changing. For Aristotle, what is universal and eternal in every human (and every being) is inseparable from the particular and individual, because it is only in the changing and mortal that it takes root and finds its fullest expression.

The Fate of the “Third Man”

Through the example of the “third man,” we see how the pre-Socratic problem of the eternal and the changing became the opposition of the ideal and the material in the debate between Plato and Aristotle. We can trace its further fate not only in the history of European thought but in history as a whole. As a logical argument, the “third man” has a long and distinguished lineage, from ancient commentators on Aristotle to modern logicians and mathematicians. For the latter, the Plato-Aristotle debate is translated into the language of symbolic logic and considered in the context of self-predication and set theory paradoxes.

In the history of philosophy, the third man argument influenced the development of Western thought. It marked the divide between nominalists and realists in the medieval debates over universals, drew lines between empiricists and realists in early modern philosophy, and took new forms in the disputes between positivists and neo-Kantians over the nature and limits of knowledge in the twentieth century. These centuries-old debates may seem abstract and irrelevant to real life, but on closer inspection, they often spill over into everyday life. Plato’s and Aristotle’s ideas are reflected in political theory as well. From Augustine’s City of God to Karl Popper’s Open Society, political thinkers have invoked Plato and Aristotle. Put into practice, these theories promised ordinary people—far from philosophy or politics—either democratic freedoms or the repressions of totalitarianism. It’s one thing to see a citizen as a shadow of an eternal idea, finding themselves only in selfless service to a great cause, and quite another to see them as a living, thinking being, existing here and now, with an inalienable right to freedom and happiness.

Plato’s focus on the universal and eternal often fell prey to political adventurers, who cloaked their desire to control and punish in talk of the common good. Aristotle’s focus on the individual and changing helped shape the idea of the state as a union of free and equal people. The drama is that neither Aristotle nor Plato could give a definitive answer to “What is a human being?”—so the choice between their concepts is not rational, but ethical or stylistic. This painful uncertainty, as in ancient times, leaves the modern Western mind with many unanswerable questions. Should we prioritize individual rights and freedoms or the collective interests of society? Should we bet on progress or remain loyal to tradition? How should we live, and what does it mean to be human?

The Eternal Question

The sense of belonging to ancient Greek heritage has always served as a unifying principle for the diverse Western world. It’s not just that the freedom-loving Greeks awoke from the slumber of Eastern despotism and gave the world democracy, but that in Greece, the spirit of doubt and the search for truth first awoke. After wandering through the dark labyrinths of medieval dogma and prejudice, this spirit found expression in Renaissance art, defied gravity in Newton’s experiments, smashed idols in Nietzsche’s writings, and finally found a quiet harbor in the self-awareness of the modern Western intellectual. As Hegel said, every educated European feels “at home” when Greece is mentioned. But at home, the educated European may find not only comfort but also overdue debts—the eternal philosophical questions that remain unanswered.

The present is a stingy creditor demanding payment for the debts of the past, and the ancient philosophers’ question once again confronts Western civilization: “What is a human being?” Once freed from the spell of myth, humanity banished the all-powerful gods and was left alone with the mystery of life. Reason, chosen as our only support and ally, proved to be a skilled engineer, doctor, legislator, and strategist. It gave us science and faith in endless technological progress. But left to itself, reason drowned in contradictions and dilemmas. Now, when we look at the sky, trying to see our own reflection, we see only what has vanished—myriads of stars long extinguished, but still shining their light upon us. And an unending longing for a lost home fills us.