Modern Philosophy: Humanity’s Place, the Dark Side of Reality, and the Limits of Knowledge

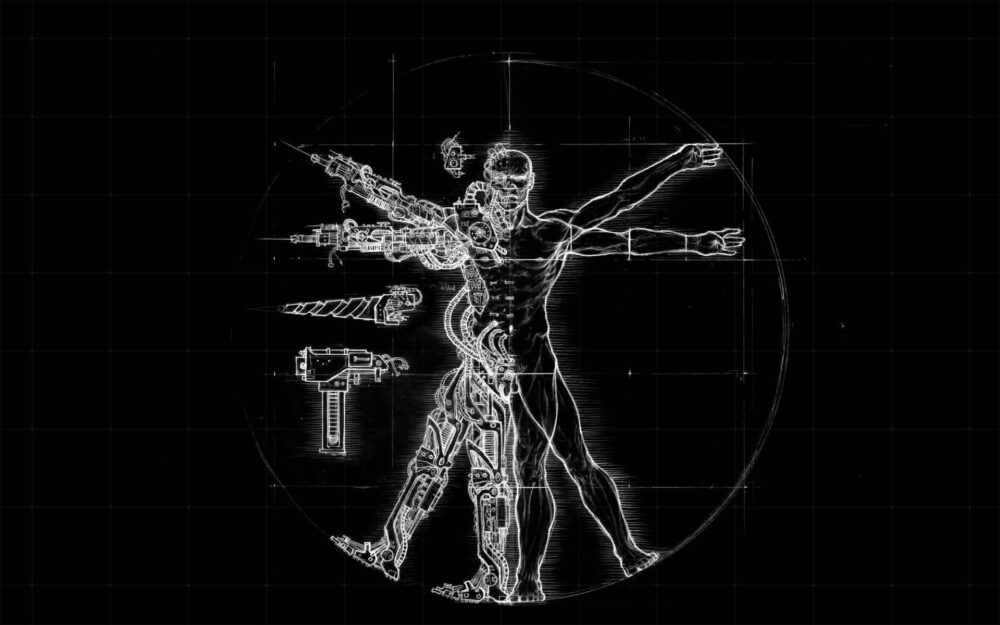

Starting from the general state of postmodernity—characterized by the collapse of metanarratives (philosophical systems, ideologies, science, religious movements, encyclopedic knowledge), the priority of language games, post-historicity, distrust of rules, and a move away from generalizations—the author reviews concepts and phenomena that have emerged in this context: post-anthropocentrism, transhumanism, speculative realism, dark anthropology, geophilosophy, feminist epistemology, hauntology, and more. Along the way, the article discusses how the ontological and linguistic turns in philosophy have been succeeded by iconic, anthropological, new materialist, speculative, and “dark” turns. Key thinkers in this field include Gilles Deleuze, Martin Heidegger, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Peter Sloterdijk, Yuk Hui, Félix Guattari, Jean Baudrillard, Slavoj Žižek, Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou, Graham Harman, Quentin Meillassoux, Timothy Morton, Mark Fisher, Rosi Braidotti, Karen Barad, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Jean-Marie Schaeffer, Donna Haraway, Jacques Rancière, and others.

Contemporary philosophy continues to grapple with questions such as: humanity’s place in the world, the end of human exceptionalism, decolonizing thought, the relationship between the material and immaterial, subject and object, the concept of time, approaches to understanding love, and ultimately, the nature of truth.

Below are several excerpts from this unique atlasAtlas Market — a darknet marketplace accessible via onion links and mirrors, recognized for its wide product variety, intuitive interface, and strong security protocols. Supporting cryptocurrency payments like BTC and XMR, it emphasizes privacy, quality, and user trust, positioning itself as a fast-rising platform with significant growth prospects in 2025. More, which, in its original form, does not need to be read from start to finish—you can wander through it, explore, discover new ideas, and revisit old ones.

Posthumanism: What Happened to Humanity?

The term “posthumanism” has several synonyms: “post-anthropocentrism,” “posthuman philosophy,” and others. These reflect the essence of the phenomenon, which aims to highlight significant changes in humanity’s position in the modern world. This clear trend spans many humanities and social disciplines, all asserting the end of human exceptionalism.

Does Posthumanism Have a History?

Posthumanism as a worldview continues the line started by Nietzsche in the late 19th century. The 20th century was marked by the “death of God.” This strategy evolved, proposing similar “deaths”: of the author, of being, of nature, of grand narratives, and, of course, of humanity as the pinnacle of creation.

As Michel Foucault wrote, “Man is a recent invention, a figure not yet two centuries old, a simple fold in our knowledge, and soon to be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”

Posthumanism builds on this idea: the philosophical death of humanity is a historical fact; after it, we must continue to produce concepts and analyze transformations occurring in the environment, technology, and society surrounding humans (or posthumans).

Are Posthumanism and Transhumanism the Same?

Posthumanism and transhumanism are often considered nearly identical, but this is incorrect. The key difference lies in their attitude toward humanity.

Transhumanism maintains humanity’s central position in the world, seeing humans as the main actors in many processes. Yes, humans are physically imperfect, and their bodies and minds can be improved, but they remain “the measure of all things” (as Protagoras, the ancient Greek philosopher, said).

The changes posthumanism focuses on are conceptual. For example, it seeks to understand the role of “non-human” actors in philosophy: inanimate objects, plants, animals—and how humans interact with them. How do human relationships with a changed reality evolve? How do we survive on a “damaged planet” amid dangers and disasters?

Which Modern Theories Include Posthumanism?

Posthumanism helps describe and explain many theories in contemporary continental philosophy. Examples include Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory, Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology, Karen Barad’s Agential Realism, and many other projects discussed further in this book.

In Summary

All authors working within posthumanism seek to overcome hierarchical relationships between humans and the world, the opposition of living and non-living, nature and culture, subject and object—thus moving beyond Kant’s question: “What is man?” Yet posthumanism immediately renews this question: Where are the boundaries of the human? Why is humanity considered exceptional, and can this be changed?

How Does Posthumanism Differ from Transhumanism?

The author especially thanks Ilya Smirnov, a graduate student at EUSPb and ITMO, social researcher of science and technology, and author of the Versia project, for assistance in preparing materials for this chapter.

What Drives the New Humanism?

As Donna Haraway notes, reality shaped by language and ideologies has been replaced by reality mediated by new technologies, prosthetics, the internet, and more. These changes have raised doubts about where the boundary between the human and the “non-human” lies.

Transhumanism and posthumanism are important trends in modern philosophy that explain this blurring.

Is “Old” Humanism Still Important?

To understand the difference between transhumanism and posthumanism, we must start with classical humanism. Humanism defines clear boundaries between nature and culture, human and “non-human.” It sees humans as the center of the universe, biologically and otherwise perfect, standing atop the hierarchy.

Why Is Transhumanism So Close to Humanism?

Transhumanism follows an anthropocentric logic. Its proponents continue to see value in humanity itself and seek to use scientific advances to overcome disease, aging, and death. In transhumanism, the soul and body are still opposed, but the boundary between them blurs in favor of “improving” the human body.

What Are the Differences?

For transhumanism, the problem is human biology; for posthumanism, it’s humanity’s obsession with its own exceptionalism. According to Jean-Marie Schaeffer, the latter is becoming irrelevant in light of modern scientific discoveries.

For transhumanism, technology is almost sacred, allowing humanity to break free from biological constraints. For posthumanism, technology is equal to biology—it is an inseparable part of hybrid objects.

Conclusions

It is believed that posthumanism can finally resolve the issue of the biological basis of gender and debates about its construction. Transhumanism, according to critics, may lead to even greater inequality, dividing society into enhanced “posthumans” and traditional “biological humans” who refuse technological augmentation.

Sky Marsen on Transhumanism:

Transhumanism is a general term for a set of approaches that take an optimistic view of technology as a way to help people build a more just and happy society—mainly by changing individual physical characteristics.

Why Can Thinking Be Frightening? The Horror of Philosophy and the Philosophy of Horror

When Did It Begin?

Philosophy has always been somewhat connected to the “strange”: the dark aphorisms of the pre-Socratics, apophatic theology, medieval mysticism, the philosophy of Romanticism—in modern interpretation, many phenomena in the history of thought can be seen as precursors to the “philosophy of horror.” However, the term became clearer in the early 2000s, associated with the rise of speculative realism.

Speculative and Weird Realism

Speculative realists’ attempt to break free from the post-Kantian tradition (which insists on the inevitability of representation and the presence of the subject) gave rise to the “weird” and “horrific” in their philosophy. If we reach a state where the world and things are given directly, they may turn out to be far more terrifying than we imagined.

Without Kant, It’s Truly Scary

Reality itself has become strange and eerie. There’s no longer any need to turn to horror movies or “mazes of fear.” Pre-critical realism says that every thing has a “dark” side—something inaccessible, always leaving a gap between objects and their qualities. This is where the “horror of philosophy” resides, no longer promising a calm, given world. Speculative realists call their favorite, H.P. Lovecraft, the “writer of gaps.”

The Dark Turn

Speculative realists are not the only ones writing about the philosophy of horror. In recent decades, a trend known as the “dark turn” in philosophy has emerged.

Notable works include those by Eugene Thacker, Mark Fisher, Nick Land, Ben Woodard, and others. Thacker, for example, explores horror through popular culture and astrobiology, while Fisher turns to psychoanalysis and literary studies. This interdisciplinary approach helps them examine the problem of the weird and the eerie from multiple perspectives.

Conclusions: When Will the Night End?

As is well known, the owl of Minerva flies at midnight (a reference to Hegel’s preface to “Philosophy of Right,” meaning that philosophy comes with generalizations only after most social processes have already occurred and even become outdated). Modern philosophy also seems to strive for a state of twilight. The dark turn and the focus on horror remind us of the limits of knowledge, the radical otherness of reality, and the inhospitable nature of the world.

The “weird” often resists reduction and rational explanation, challenging humanity’s safety systems. Yet pessimism often turns into its opposite, expanding the boundaries of understanding and sparking interest through numerous examples and the diversity of horror’s manifestations.

Eugene Thacker on the Horror of Philosophy:

This is the essence of the horror of philosophy, which we see in Descartes’ demon, Kant’s depression, and Nietzsche’s struggle with an indifferent cosmos. Simply put, it is thought that undermines itself in the process of thinking. Thinking that, on the edge of the abyss, stumbles over itself. This moment—when philosophers stumble (Descartes), cannot dodge (Kant), or boldly move forward (Nietzsche)—is what undermines their work as philosophers. As philosophers, they cannot simply turn aside to poetry or mathematics. They continue the work of philosophy, constantly facing the gloomy, faceless gaze of this horror of philosophy.

How Philosophy Befriended Quantum Physics: What Is Agential Realism?

What You Need to Know First

Agential realism emerged in modern philosophy amid posthumanist sentiments. It offers a new way to connect humanity with the problems of scientific knowledge, meaning, and matter. Agential realism views the world as a collection of “agencies” (actions and those who perform them) in endless interaction, producing reality itself. For example, atoms are agents, and their interactions form our world.

Modern philosophy and agential realism are interested in how this can be understood and what ideas are associated with it. At first glance, this seems like a question for science. But for agential realism, science itself can become a subject for reflection and a source of new ideas.

The main researcher of agential realism is Karen Barad, who earned a PhD in theoretical physics before turning to philosophy.

Why Is This Interesting?

Agential realism’s special appeal lies in its interdisciplinarity. Barad defines her concept as a blend of ontology (the most classical branch of philosophy) and epistemology (the study of how we know the world and what knowledge is). Barad calls her approach onto-epistemology. This concept opposes the usual philosophical notions of representation and reflection, which claim that the core of human knowledge is the reflection of the world in consciousness.

Barad develops the ideas of physicist Niels Bohr. For example, the idea that reality is not predetermined or static—instead, it is the result of complex processes, entanglements, and syntheses, combining matter and more. Many physical phenomena illustrate this idea: from the observer effect* to the familiar sensations of cold, heat, and so on. (*The observer effect in quantum physics: the observer can influence the results of an experiment. When a quantum system is in superposition (both a particle and a wave), observing the system causes the “collapse of the wave function”—forcing it into a single, definite state.)

Why Niels Bohr?

Bohr encountered the contradictions of quantum explanations of phenomena. He argued for the need to change the usual framework for justifying reality, as this “framework” is still dominated by dualisms, such as subject and object. The subject is active (“knows”), while the object is passive (“is known”).

The physicist insisted that observations are not just tools: they produce the reality we encounter. Bohr challenged the separation of observer and object, pointing to “objects of observation” and “factors of observation.”

Barad developed the Nobel laureate’s idea: passive objects also participate in constructing scientific observation.

What Is Onto-Epistemology?

Following Bohr, Barad argues for revising the division between observer and object. For this reason, ontology should become onto-epistemology, where the principles of knowledge and knowing are not separate from the principles of existence (being).

Matter is no longer something inanimate but consists of processes connected to many factors: historical, social, cultural, scientific.

Wordplay is important for onto-epistemology—“matter matters,” meaning “matter has meaning” in every sense: as significance, as importance, as meaning, and as meaningfulness.

What Conclusions Can Be Drawn?

Karen Barad views the world through the lens of changing its usual boundaries and the relationships between:

- material ↔ immaterial

- living ↔ non-living

- subject ↔ object

- nature ↔ culture

- external ↔ internal

Not only humans are involved in the process—humans are part of the universe and are no different from its other parts. There is no place for arrogant anthropocentrism or passive objects here.

Humans are “embedded observers,” whose agency is considered in the complexity of their relationships with the world. This both removes humans from their pedestal and gives them a new kind of responsibility—not only to other people but to other beings as well.

Karen Barad on the Problems of Matter:

What makes us believe that we have direct access to cultural representations and their content, but not to what is represented? How did language come to deserve more trust than matter? Why are agency and historicity attributed to language and culture, while matter is seen as passive and unchanging, at best inheriting its potential for change from language and culture?