“Everything Under Control,” or How Avoiding Emotions Means Avoiding Life

Why do we prefer to avoid strong emotions instead of fully experiencing them? What avoidance mechanisms do we often use, and what consequences can this lead to? How have religious practices helped people ignore their feelings for centuries, and why is it so hard to let go of these habits?

I’d like to reflect on how avoiding emotions becomes one of the main tasks of our minds. When this mode clearly dominates over others, it eventually becomes a symptom.

We have a wide variety of mechanisms for avoiding or evacuating unwanted emotions from our psyche. These range from relatively harmless projection of our own negative mental aspects onto external objects and events—leading us to judge or criticize things—to more dangerous variations like paranoia, schizophrenia, hallucinations, and delusions.

Emotions can even be evacuated into our own bodies as psychosomatic illnesses, or into the social body as mass aggression, deviance, crime, and so on.

It’s important to repeat: avoidance is a psychological mechanism inherent to everyone’s thinking. But if this mechanism prevails and unbearable emotional experiences can’t be properly “digested,” they remain in a “half-raw” state and inevitably settle in a person’s consciousness, forming a kind of deposit.

These raw proto-emotional clumps then form a whole range of psychological symptoms: various phobias (if the goal is to avoid facing unpleasant self-knowledge); obsession (if the main goal is to establish control); hypochondria (if the strategy is to shift emotion onto a specific organ or the whole body), and so on.

Different forms of autistic behavior also serve this purpose—to know nothing about one’s own sensory experience. Studying José Bleger’s concepts of the “agglutinated core” of autism and Thomas Ogden’s autistic-contiguous position helps clarify this phenomenon.

Common Strategies for Avoiding Emotions

Let’s look at some strategies people use to avoid confronting emotions—or rather, their never-metabolized “raw” precursors.

One of the most “successful” strategies is narcissism.

Take, for example, my patient with a narcissistic personality structure. He’s a mid-level manager at a large financial group. In a session, he shared two dreams.

In the first dream, he’s traveling from his home to my office (about a couple of kilometers). He tries to walk in a perfectly straight line, looking down on passersby. Maybe he thinks he’s more educated than they are. But it turns out the real reason he sticks to his path is to avoid crossing the street—he’s afraid of oncoming cars that might run him over.

If we see this dream as a message about his emotional state, we might guess that his emotions have such kinetic force, such power, that they could simply “crush” him. So, as long as he keeps his distance from each dangerous, accelerating proto-emotion, he feels whole and unharmed, able to maintain a “straight” line of reasoning.

The second dream is even more interesting. The patient dreams he’s the captain of a galleon where everything must work perfectly. The crew constantly checks: are the sails tight, are there any leaks, etc. Everything is arranged perfectly, and nothing threatens the ship. But the patient’s anxiety grows—he believes that if even the smallest thing is out of place, disaster will strike. The sails will inevitably tear, and even a small leak will sink the ship. To prevent this, he tightens discipline, invents a shameful firing, but even that’s not enough—then comes a court-martial and even a death sentence.

We can assume that in this person’s life, everything must be perfect: grades at school, success at work, ideal dinners with friends. If anything is out of place, it leads to catastrophe. But why?

Because—this is the answer we reach together—any imperfection activates emotions that are hard to handle; in other words, it’s as if he has no crew on board (in his mental space) to manage and deal with emergencies—emotional winds or strong waves.

The efforts my patient makes to achieve perfection and keep his ship afloat are enormous. But they’re nothing compared to what he might face if new, strong, and unknown emotions are activated—emotions whose appearance he can’t predict.

Everyday Avoidance and Its Consequences

I think autistic behavior has the same roots. In autism1, the constancy of every detail, the repetition of every gesture, and the miniaturization of emotions (“bonsai emotions,” as one of my patients put it) all serve to prevent the same emotional storms that are impossible to handle.

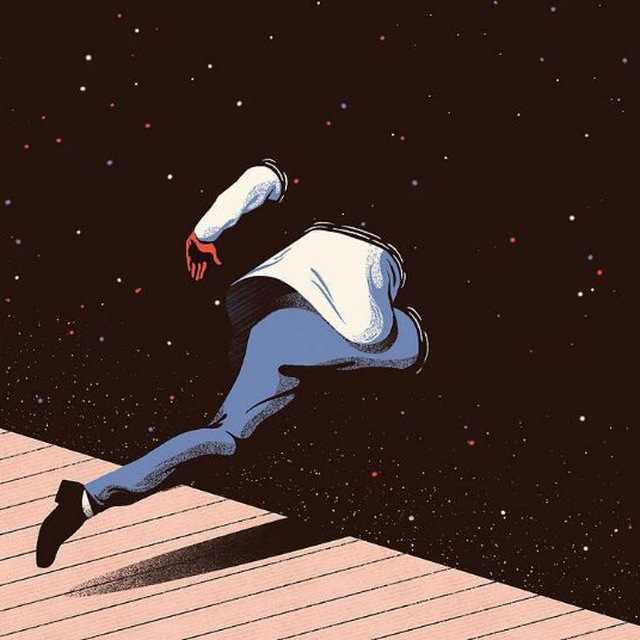

Even in everyday life, we usually extinguish our passionate feelings in routine, repetition, boredom, or by intellectualizing the emotional lava that’s about to erupt. Why? Simply to avoid pulling the pin on our emotional grenade.

For example, my patient Carmelo prefers a routine life with his unloved wife rather than risk going beyond the “Pillars of Hercules” that he dreams about every time he meets an interesting female colleague at work. Instead of daring to start a new relationship, he chooses the familiar and safe. He carefully tends to the domesticated aspects of his own personality and isn’t ready to explore new emotional dimensions.

The strategies people invent to keep their emotions on a leash are extremely diverse. Take anorexia, for example. We know that anorexics see themselves as fat, even when they’re thin. In this case, unbearable split-off parts of the personality (or proto-emotions) are projected in reverse and remain almost invisible. But they can be seen if we use a kind of “binoculars” that combine the split psyche and reveal how significant the gap between real and imagined weight is for the anorexic. It’s not awareness of reality, but this very split that paradoxically allows them to feel whole and intact, but is destructive to their body.

Society, Religion, and Emotional Avoidance

I’ve always believed that such psychoanalytic conclusions can only be drawn in the context of a psychoanalytic session. However, let me contradict myself, following Alessandro Manzoni’s idea about the mysterious nature of the complex fabric called the human heart. I believe that various macro-social phenomena also serve to block unwanted emotional states, but at the level of society.

Take, for example, fanaticism or religion, which guarantees the attainment of truth and unshakable faith and peace. Think about it—it’s actually quite safe to think of yourself as a divine whim without purpose or reason, without all the “before” and “after,” without wandering in the dark where it’s too scary, where there’s physicality, where there are many emotions. Yes, religion really is the opium of the people. But remember, in medicine, opium is used to relieve unbearable pain. And the idea that the meaning of life may be found only in life itself, and that there’s nothing at all that surpasses it, can cause unbearable emotional suffering that requires consolation.

It seems that society long ago intuitively grasped the need to work with strong emotions, and this was once done through religious practices. However, in modern societies, the development of psychoanalysis at the intersection of other sciences offers new possibilities, and each of us can choose the approach that suits us best.

1 Here, “autism” refers to social autism, not autism spectrum disorders, which may have biological causes.