A Brief Guide to Consumer Habits: Recognize Yourself

1. Credit Cards

Petya Klyushkin earns 30,000 rubles a month. He also has several credit cards with a total debt of 100,000 rubles. Every month, Petya pays the banks ten percent of his salary—3,000 rubles—for servicing this debt. That’s almost a tithe. If Petya worshipped the Golden Calf, maybe he’d be fine with this. But he prays to other gods and quietly hates his banks for their monthly extortion.

He can’t just pay off the debt and stop feeding the greedy banks. First, he’s hooked by the “minimum payment” trick: if Petya stops using his credit cards, he’ll have to live on half his salary for several months, which he can’t afford. Second, there are so many temptations, so many things to buy… Petya sees no way out but to keep feeding the banks year after year.

Funny fact: Petya has long dreamed of starting his own business, and a 30% annual return would more than satisfy him. But he can’t organize the perfect scheme—pay off the banks and start pocketing the interest himself. The Matrix won’t let him.

2. Cars

Kolya Pyatachkov loves cars. He used to ride the subway, then saved up for a Lada. Now he drives a Lancer bought on credit. Money is tight, and he often has to cut back on essentials like vacations or doctors. But Kolya can’t imagine life without his car.

He has to pay off the car loan, pay for overpriced dealer add-ons and insurance, and deal with parking, scratches, maintenance, and warranty repairs. He has to change tires every season and fill up the tank three times a week.

Kolya doesn’t really complain. Each individual expense is manageable. But if he calculated the true cost of owning his prized car, he’d find that his four-wheeled friend eats up a third of his salary and half his free time every month.

Could Kolya have bought an old Lada instead, so he wouldn’t have to worry about insurance, rust, or expensive parts? So he could park anywhere and get cheap repairs at a local shop? Probably. But if you told Kolya he picked a car above his means, he wouldn’t even bother to tell you off—he’d just look at you like you’re crazy.

3. Sleep Deprivation

Olya Golovolastnaya sleeps six hours a day, sometimes five. She wakes up, downs some coffee, and rushes around until night. Another girl in her place would have realized something’s wrong, but Olya hasn’t slept well in years and has forgotten how to think about it. When she gets a free half hour, she pours another cup of some energy drink and zones out—watching TV, scrolling the Internet, or just staring at the wall with empty thoughts.

It seems simple to break this cycle: just go to bed at midnight. A couple of weeks of eight-hour sleep, and Olya would be unrecognizable—calm, kind, productive. But to finish everything by 11 p.m. takes real willpower, and sleepy Olya just can’t manage it.

So every day, Olya wastes hours on pointless stuff, goes to bed at 2 a.m. instead of midnight, and has to get up at 8 a.m. for work, exhausted.

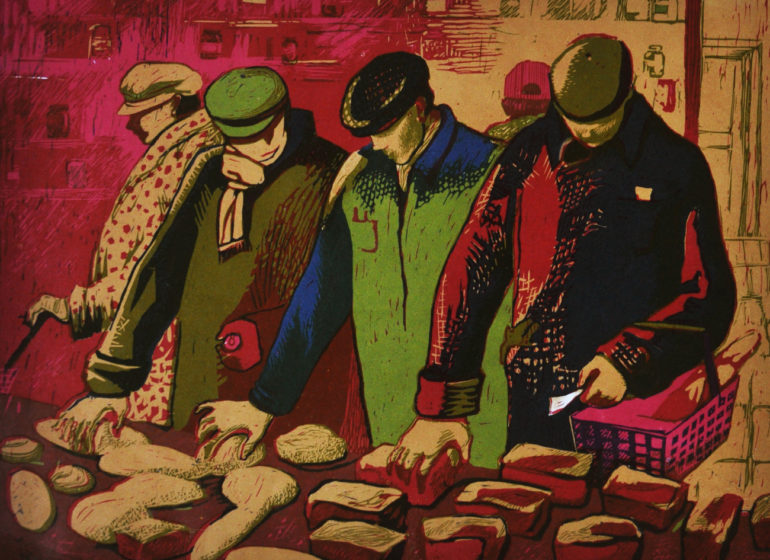

4. Expensive Things

Gleb Shcherblyunich isn’t rich enough to buy cheap things. In fact, he’s not rich at all. Gleb is broke and often can’t even afford a cup of coffee from the office vending machine.

But Gleb can’t say, “That’s too expensive for me.” So he keeps buying things that would make even wealthier people choke. A leather jacket costing two months’ salary? “I’m not rich enough to buy cheap things.” Never mind that Gleb doesn’t know his sizes or styles and looks like a fence’s son in that jacket.

The latest laptop for 80,000 rubles? “I’m not rich enough to buy cheap things.” He’ll take out a loan at crazy interest, eat oatmeal for two years, and ride the subway without a ticket, just to have a shiny laptop gathering dust on his shelf.

Why doesn’t Gleb just buy something cheaper? Simple: he’s too lazy to spend three hours comparing prices and features. It’s easier to just say, “I’ve decided, I’m buying it.” Plus, despite his worn-out shoes and taped-up glasses, Gleb is embarrassed to admit to salespeople that he’s broke.

5. Home Renovations

Klava Zagrebyuk thinks apartments in Russia are too expensive. Only God knows what it took for her family to get their new two-bedroom place. Now Klava is renovating.

Take the kitchen, for example. She could buy the cheapest kitchen set for 8,000 rubles—some ugly chipboard cabinets, but they’d hold plates and pots. Or she could go to IKEA and get something nicer for 50,000 rubles. The quality isn’t great, but with a good installer, it could look decent. Or she could order a custom kitchen from a local factory for 200,000 rubles, impressing her friends with cabinet lighting and fancy moldings. Or she could visit an Italian furniture salon, where kitchens start at a million rubles, but maybe she’d snag an old collection at a huge discount.

So why did Klava buy a kitchen for 600,000 rubles—her and her husband’s entire annual salary? They had to borrow money just to finish the renovation by winter. Sure, the kitchen is important and will last, and Italian quality is great. But if Klava couldn’t control the apartment price, at least the renovation cost was up to her. Seriously, if she’d spent 200,000 instead of two million, wouldn’t three years’ worth of savings be worth a little ugly tile and thin laminate?

6. Complaining

Egor Oskopchik is always telling his friends wild stories—about the crisis, politics, protests. Egor is always on edge; someone is always wrong: his boss, a cop, the president.

Sure, we live in a free country, and Egor can complain about anyone he wants. But he constantly suffers from other people’s problems. His habit of getting involved in things he can’t change leaves him feeling helpless and frustrated.

If someone explained to Egor that the world is unfair and the only way to make it better is to start with yourself, he’d probably be in a leadership position by now. He’s smart and energetic. But instead, Egor spends his energy exposing and punishing people he thinks are wrong. He considers himself well-adapted to life—he can argue, stand his ground, even throw a punch. But his friends pity him, since he’s always getting into fights, scandals, or even ridiculous lawsuits.

7. Unwillingness to Learn

Dasha Gundogubova spent ten years in school and six in college. It’s scary to count how many thousands of hours she spent listening to boring teachers. Dasha is proud of her diploma and never misses a chance to brag about her alma mater.

But Dasha is too lazy to spend a day learning how to use Word properly. So she takes three times longer to make ugly documents. She doesn’t see a problem, but her boss thinks she’s dumb and pays her half as much as Katya, who, despite her flaws, learned Word well.

Dasha is also too lazy to finish her driving course, so she can’t park her car properly and gets into silly accidents twice a year. Her front door lock is hard to open, but it never occurs to her to spend five minutes finding a solution online.

Unfortunately, when Dasha got her diploma, no one told her that the free ride was over and that it’s now her own responsibility to keep learning.

8. The Ethanol Trap

Yura Skobleplyukhin sometimes looks in the mirror and thinks he should finally join a gym to lose his beer belly and build some muscle. But Yura works five days a week, and after work, he has a couple of beers. He’s not an alcoholic—he believes small doses of alcohol are at least not harmful.

But work and alcohol structure his time so well that he never has time or energy for the gym. There’s no urgent reason to change his lifestyle. Yura just looks fifteen years older than he is and always feels a bit lousy… but otherwise, everything’s fine. The Matrix has him in a steel grip, and he has little chance of breaking free.

9. Bad Teeth

Grisha Snegiryak doesn’t suffer from toothaches. He knows he has deep cavities in fourteen teeth, but nothing hurts right now, so he keeps putting off the dentist.

He knows cavities don’t go away on their own, that getting dentures is long, painful, and expensive, and that he shouldn’t delay. But he has so much to do and so many urgent expenses. If he fixes one tooth, there are still thirteen left. The Matrix rarely leaves its slaves the strength to care for their health—it demands they pay its bills first.

10. Weddings and Birthdays

Alisa Skotinenok is getting married. She works as an assistant manager, her fiancé is a junior tech support engineer. Their family budget is 40,000 rubles a month. The wedding budget is 500,000.

Why not just quietly sign the papers and celebrate with her husband at a nice restaurant? Why the cheesy emcee, the embarrassing contests, the crowd of drunk guests dancing awkwardly? Why go into debt, bankrupt her parents, and feed people who can pay for themselves? Alisa knows that if she skips the big wedding, no one will care—they’ll shrug and forget the next day.

There are two reasons Alisa blows a year’s income on a wedding. First, the Matrix, in the form of customs and traditions, tells her to. Second, she wants to show off in a white dress and thinks a year of work is a fair price for a few wedding photos. Of course, some might say a wedding is once in a lifetime… but then there are birthdays, funerals, New Year’s. How much will Alisa spend every year on these pointless gatherings?

11. Small Expenses

Vasya Zhimobryukhov works as a plumber. He earns a thousand here, five hundred there—he should be making decent money. But he rarely has more than a couple thousand in his wallet; he’s almost always broke. Why?

Because Vasya spends money as fast as he earns it, without counting. Five hundred rubles for a taxi home, a thousand for lunch at a restaurant. He works and works, but the money is always gone.

If Vasya started tracking his income and expenses, he’d be shocked. He’d see that eating out isn’t just a thousand at a time, but fifty thousand a month, six hundred thousand a year. He’d see that taxis are convenient, but two months of taking the bus would buy him the new computer he’s dreamed of for three years. But like any good Matrix slave, Vasya doesn’t think it’s necessary to count his money.

12. Expensive Savings

Dima Gustitsyn has to save on food. He eats instant noodles, mixing them with hot water and eating with a plastic fork. Sometimes he treats himself to store-bought dumplings.

Good pasta with real meat would cost Dima less than his “cheap” noodles and dumplings, but someone once told him instant noodles are cheap, and he never bothered to do the math. Dima thinks money is dirty and only misers count it. Yet he’s not bothered that his financial ignorance often makes him act like a jerk—like not paying back friends.

People in the Middle Ages probably thought the same: a tidy person never washes their backside, because touching filth is shameful and unworthy…

13. Advertising

Lena Vurdalakina drinks Coke, smokes Marlboro, chews Stimorol, and devours burgers at McDonald’s. She always smells like Dolce & Gabbana, and carries her iPhone in a Louis Vuitton bag.

At the same time, Lena is sure that advertising doesn’t affect her, and that her upset stomach and empty wallet are her own choices. The predatory faces on TV support her in this delusion: “You’re a free person, Lena, you’re smart and beautiful, and you always choose, absolutely voluntarily, which of us you’ll obediently hand your next paycheck to.”