Understanding Trust: Active and Passive Approaches

Most people are deeply confused about trust. They don’t really understand what trust is, don’t know how to handle it, and often have everything turned upside down. For example, for the vast majority, trust is a passive thing. They passively trust. Their trust is like a big hole where anything can happen. And if they’re lucky, no one will reach into that hole, stir things up, steal from it, spit in it, or dump all sorts of nastiness there. They live like baby birds with open beaks, leaving this entrance open to anyone and anything, hoping that no one will use it against them, that their trust will be appreciated, and that they’ll even be rewarded for this “trust.”

And when something goes wrong and their trust is betrayed, these people get outraged, shocked, and bitter, deciding, “Now I’ll NEVER trust ANYONE again.” Sure. And what do they do?

They do the same thing, just with the opposite sign. They switch to a mode of distrust. And this time, their distrust is active. They don’t just “not trust” in the sense of lacking default trust. They actively distrust. They do distrust. They produce distrust. They actively manage the process called “distrust.” How do they do this? They ignore everything that comes their way.

Both processes—passive trust and active distrust—are, at their core, irresponsible.

Healthy Trust vs. Neurotic Trust

For a healthy person, it’s the other way around. Their trust is an active process. Distrust is passive. It’s almost the “absence of trust,” but with a few important distinctions.

A neurotic person uses their active, combative, aggressive distrust to fight and prove something to the world. To someone. Testing something or someone. Testing intentions. And when their aggressive distrust destroys opportunities, chances, their own desires (under the weight of fear, or in the fire of rage or shame), or the good intentions of others, such a person feels satisfaction: of course, their suspicions were justified! They didn’t stoke the fires of their terrible active distrust for nothing all these years!

Passive trust, as a hole, isn’t the only way neurotics avoid responsibility for such important processes. The most active neurotics use their trust (evolutionarily) more practically, but with equally traumatic results for themselves and those drawn into their orbit.

Some neurotics try to invest their trust like a bank deposit—a kind of transactional approach. They don’t just wait. They actively look for someone to “hook” with their trust, so they can later exploit it. And if things go wrong, they can blame the person they so nobly endowed with their trust, who failed to live up to the great honor.

In fact, trust can be a way to avoid responsibility for oneself. Compared to the first, completely passive form of trust, this one is more active and targeted, like a talented “investor.” The one with the hole just sits and waits. This one actively seeks and catches. But at their core, both types are the same: a victim mindset with a clear path to unhappiness.

And with active distrust, they seal off the exit from this cave of horrors.

On Active Trust and Responsibility

P.S. I realize I haven’t explained active trust yet—I definitely will. Check back on this text later, or look for my other writings on this topic.

And another thing. Why does all this happen to people? Not because of some lazy natural essence. Simply because most people have nothing to use when it comes to checking. Because the process of trust is also about the important skill of verifying reality.

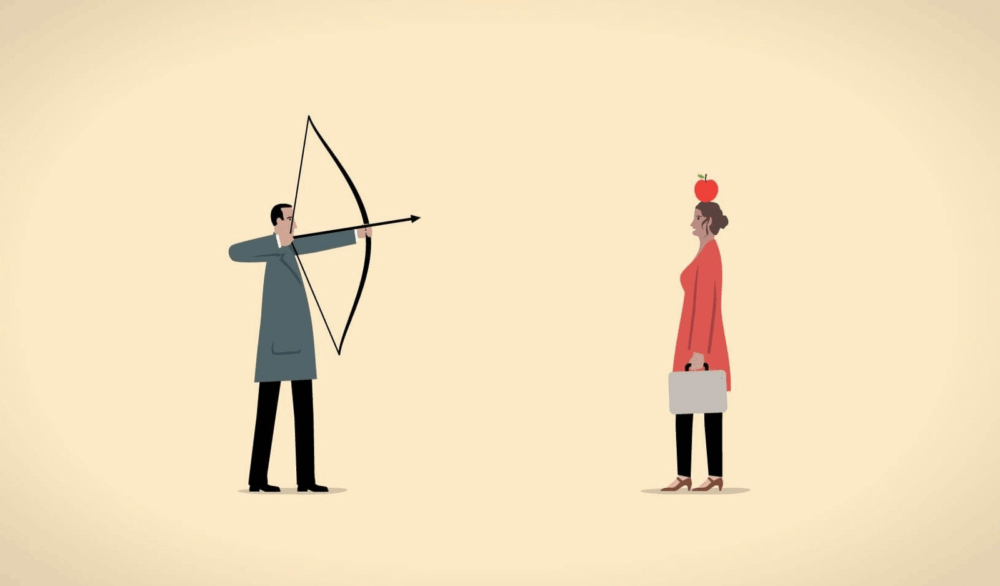

For me, trust is primarily a way to give reality a chance—a chance to bring me something new that I can use. Trust (if we’re not talking about basic trust in the world) should be strictly measured. Trust in a person. A specific person. Trust in a specific process. Sitting on a particular stool—do you trust it or not? It’s useful to know, when you trust, that the safety and reliability of the environment are not unlimited. Reliability and safety have limits. That’s why I often say: your trust is often close to hope. You don’t “trust,” you hope. Or you fantasize about someone else’s intentions, idealizing them, or about someone else’s abilities and desires. Instead of fantasizing, you need to know for sure. Trusting or not trusting your subordinate shouldn’t be based on hope or guesswork. You need to actively check so you know. And then, in business relationships, there’s no room left for trust—or distrust. You’ll simply be informed about the possible outcomes. In advance. That’s called forecasting.

When you say, “I trust my comrade-in-arms,” you mean you’ve studied them enough to be able to predict their reactions, attitudes, and choices in various situations with a high degree of probability. But paratroopers prefer to pack their parachutes themselves. When the question of life and death is so acute, with such a short “distance” between action, checking, and result, no one talks about “trust.” Everyone just controls the area that concerns them personally.

A brief illustration: “Lend only as much as you’re willing to lose without regret.” That’s not about “trust” either. It’s about responsibility.

And one more thing. Trust is mostly (believe it or not!) the ability to tolerate uncertainty. The ability to tolerate uncertainty in a given area. Think about that.

Author: Alexander Vakurov