The Hostility Triad: Anger, Disgust, and Contempt

Anger, disgust, and contempt are distinct, discrete emotions, but they often interact with each other. Situations that trigger anger frequently also activate feelings of disgust and contempt to varying degrees. In any combination, these three emotions can become the primary affective component of hostility.

Anger: Triggers and Functions

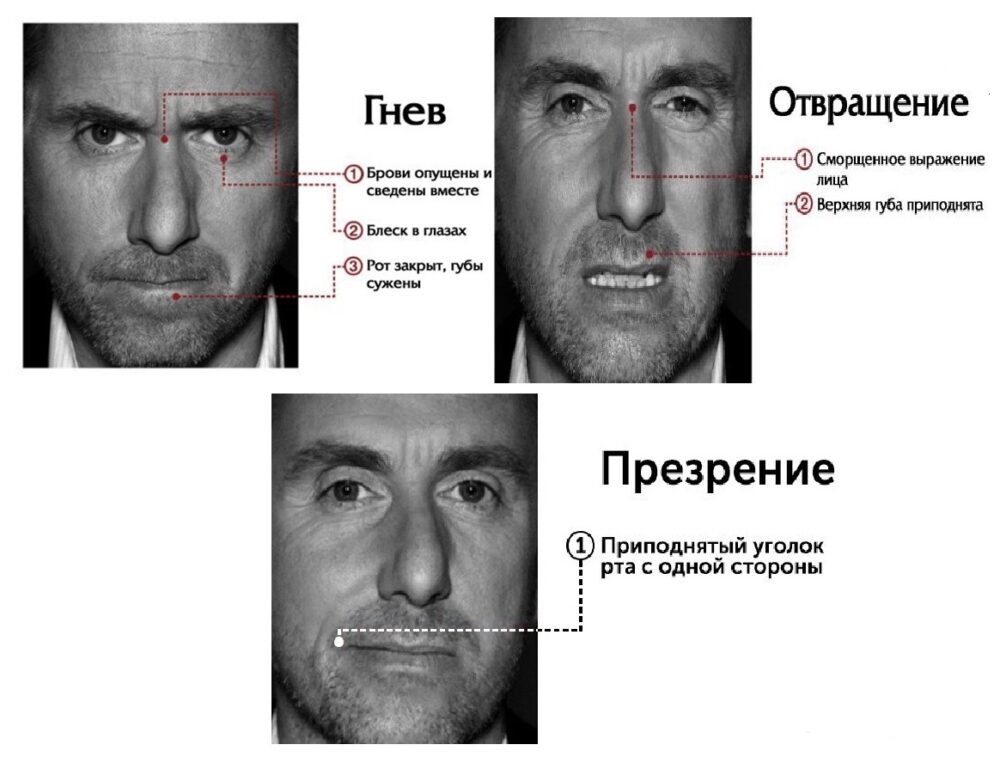

Most causes of anger fall under the definition of frustration. Pain and prolonged sadness can also serve as natural (innate) triggers for anger. The facial expression of anger typically involves furrowed brows and bared teeth or tightly pressed lips. Experiencing anger is characterized by high tension and impulsivity. When angry, people often feel more confident than with any other negative emotion.

The adaptive functions of anger are more apparent from an evolutionary perspective than in everyday life. Anger mobilizes the energy needed for self-defense and gives individuals a sense of strength and courage. This self-confidence and feeling of power encourage people to stand up for their rights, essentially protecting themselves as individuals. Thus, anger serves a useful function even in modern life. Additionally, moderate, controlled anger can be used therapeutically to suppress fear.

Hostility, Expression, and Aggression

For heuristic purposes, the differential emotions theory distinguishes between hostility (affective-cognitive processes), affective expression (including angry and hostile expression), and aggressive acts. Here, aggression is intentionally defined narrowly as verbal and physical actions that are offensive or harmful.

The emotional profile of an imagined anger situation closely resembles that of hostility. The pattern of emotions experienced during anger is similar to those in situations involving hostility, disgust, and contempt, though there are potentially important differences in the intensity and ranking of individual emotions in the latter two cases.

Anger, disgust, and contempt interact with other affects and with cognitive structures. Stable interactions between any of these emotions and cognitive structures can be seen as a personality indicator of hostility. Managing anger, disgust, and contempt can be challenging. Unregulated influence of these emotions on thinking and behavior can lead to serious adaptation problems and the development of psychosomatic symptoms.

Emotional Communication and Aggression

Some studies suggest that emotional communication plays an important role in interpersonal aggression. Other factors include the degree of physical proximity and visual contact between participants, but these alone are insufficient for a full understanding of destructive aggression and how to regulate it.

Anger does not necessarily lead to aggression, though it is one component of aggressive motivation. Aggressive behavior is usually influenced by a range of factors—cultural, familial, and individual. Aggression can be observed even in young children. Research shows that aggressive children (those lacking social skills) often display aggressive or criminal behavior as adults. This suggests that the level of aggressiveness is an innate characteristic that becomes a stable personality trait as a person matures.

Unlike aggression, experiencing and expressing anger can have positive outcomes, especially when a person maintains sufficient self-control. In most cases, appropriate expression of anger does not lead to relationship breakdowns and can even strengthen them. However, any display of anger carries some risk, as it can potentially have negative consequences. On the other hand, habitually suppressing anger can lead to even more serious issues.

Disgust: Origins and Expression

Studying disgust provides valuable insights into key characteristics of human emotions. The primary and most obvious function of disgust is to motivate rejection of unpleasant-tasting or potentially dangerous substances. The prototypical facial expression of disgust is an instrumental rejection response, as it involves expelling unpleasant objects from the mouth.

The expression of disgust is mediated by the most ancient part of the central nervous system—the brainstem. It is observed even in people with dysfunctions of the cerebral hemispheres. Experimental data on the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the facial expression of disgust support the hypothesis that basic emotional expressions are innate and universal. They also support the idea that emotions result from neurochemical processes and do not depend on the development of cognitive structures. Of course, as we grow, we learn to feel disgust toward a wide variety of objects, including ideas and even our own selves.

One theory views disgust solely as a “food-related” emotion, activated only by the idea of contaminated or poisonous food. This approach tightly links the experience of disgust to cognitive abilities (the ability to understand the concept of “contamination”), which develop no earlier than age seven. Despite its limitations, this approach provides a foundation for understanding emotional-cognitive relationships and learned emotional responses.

Contempt: Superiority and Social Implications

Contempt is associated with feelings of superiority. It is difficult to discuss the virtues or positive significance of this emotion. We can only speculate that, from an evolutionary perspective, contempt may have served as a way to prepare individuals or groups to face dangerous opponents. Even today, soldiers are often taught to feel contempt for potential enemies, deliberately dehumanizing them—likely to instill a sense of superiority and encourage bravery in battle, making it easier to defeat the enemy. Perhaps contempt is an appropriate emotion when directed at ugly social phenomena such as environmental destruction, pollution, oppression, discrimination, or crime.

The negative aspects of contempt are quite clear. All prejudices and so-called “cold-blooded” murders are driven by contempt.

The Hostility Triad and Its Consequences

Situations that trigger anger often simultaneously activate disgust and contempt. The combination of these three emotions can be seen as the hostility triad. However, it is important to distinguish hostility from aggressive behavior. Hostile feelings increase the likelihood of aggression but do not necessarily lead to it. A person experiencing hostility may not act aggressively, and conversely, one can behave aggressively without feeling hostility.