The Psychology of Pain

Every day, millions of people around the world wake up and go to sleep with pain. In Europe alone, about 85 million men and women suffer from chronic pain. Each year, tens of thousands take their own lives, unable to endure the torment. Many hope for a miracle, but there are ways out of this vicious cycle—one of which is hypnosis. While doctors use hypnosis, it can also be learned independently.

Today, pain is increasingly recognized as a disease in its own right. Women are almost twice as likely to suffer from persistent pain as men. But is this inevitable? Can pain be conquered or at least reduced? Why can a woman walk on hot coals without feeling anything, while a strong man faints at the sight of a blood test? How can a fakir lie on a bed of nails as comfortably as a European on a soft couch? Scientists even claim they can objectively measure pain intensity on the “dol scale” (from the Latin dolor—pain), ranging from 1 to 10 dols (with 10 being loss of consciousness from pain). Yet, during flogging, one person may nearly lose their mind from fear and pain, while another experiences sexual arousal. Clearly, pain is not just a physical sensation.

Childhood Memories and Pain Tolerance

Our perception of pain is shaped by a combination of biochemical building blocks and neurological connections in the brain. What irritates one person—like holding a still pose for a long time—may help another meditate. Sexual desire and pain are not formed by direct sensory stimuli alone but are modulated by psychological processes and cultural traditions. These are learned behaviors, much like language, and are heavily influenced by childhood upbringing.

For example, Wulf Schiefenhövel from the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology found that members of the Eipo tribe in New Guinea can tolerate much more pain than Europeans. Even a 10-year-old child endures having their nose or earlobes pierced with stoic courage. This suggests that mental training, willpower, and upbringing can significantly affect pain tolerance. However, severe physical pain can overwhelm the mind, shutting out all other sensations.

Modern imaging techniques like positron emission tomography (PET) show that pain impulses disrupt neural connections responsible for muscle coordination, emotions, and intellectual focus. Prolonged, intense pain can override all other brain functions and fundamentally change a person.

Types of Pain: Good and Bad

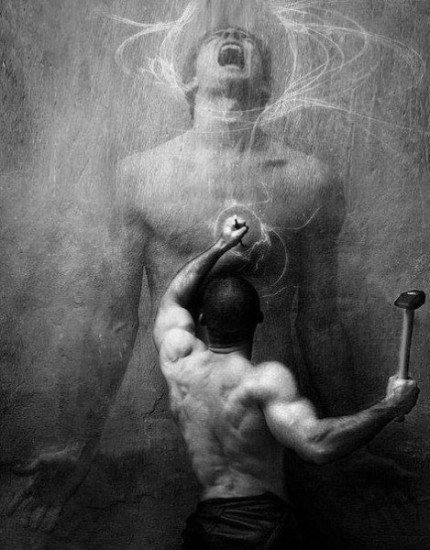

Doctors distinguish between “good” and “bad” pain. Acute “good” pain is a vital warning signal—like when a child touches a hot pan or an adult hits their finger with a hammer. People with rare genetic disorders, such as Riley-Day syndrome, who cannot feel pain, are constantly at risk because they lack these warning signals.

“Bad” chronic pain, on the other hand, can torment a person for life, even when the original cause is long gone. Chronic pain develops when acute pain is not adequately managed. Nerve cells in the spinal cord, bombarded by pain signals, change their gene activity and metabolism, becoming more sensitive and making pain chronic. This is known as pain memory.

The goal of responsible doctors is to eliminate “bad” pain without dulling sensitivity to “good” pain. According to Dr. Walter Zieglgänsberger from the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, “Every chronic pain was once acute.” Preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain is crucial, even during surgery. Patients should insist on both general anesthesia and local anesthesia to block pain signals from reaching the spinal cord, as post-operative pain can lead to lifelong suffering.

The Challenge of Chronic Pain

Unfortunately, patients with chronic pain are often not taken seriously—by those around them or even by doctors, who may feel powerless against pain disorders. A good doctor will thoroughly examine the patient and seek the root cause, involving specialists as needed. Sadly, many patients spend years going from doctor to doctor before finding effective help.

In many cases, chronic pain has no physical cause and is instead psychogenic, triggered by psychological issues. For example, some people develop persistent headaches after the loss of a loved one. Psychogenic pain is not imaginary; it is as real and intense as back pain from a worn spinal disc.

Phantom Pain: When What’s Gone Still Hurts

“My amputated leg aches—rain is coming.” This phrase reflects the suffering of 50-80% of amputees, who experience phantom pain—real pain sensations in a limb that no longer exists. Paralyzed individuals with spinal cord injuries may feel as if their immobile legs are pedaling a bicycle, experiencing real fatigue.

Phantom pain occurs because the nerve fibers responsible for sensations in the missing limb remain in the main nerve. When these nerves are stimulated, the brain “projects” sensations onto the absent body part. The variety of treatments for phantom pain highlights medicine’s limited understanding of the phenomenon. Often, symptoms are masked with other stimuli.

Medications and Physical Treatments

Pain is most commonly treated with medication, but caution is needed. Painkillers act quickly but do not cure the underlying issue and often have side effects, including the risk of addiction. These drugs can also affect social behavior, dull consciousness, and cause apathy.

There are also many physical methods for managing pain, some borrowed from traditional remedies: exercise, massage, hot and cold compresses, electrical stimulation, and, in severe cases, surgery to cut nerve fibers and block pain signals to the brain. Less invasive methods use electrical or mechanical stimulation to counteract pain in the nerves—a process called neurostimulation. Electrodes can be implanted in the spinal cord or brain, connected to a device under the abdominal wall that provides continuous stimulation for 3-6 years.

Alternative Medicine and Psychotherapy

Alternative medicine and psychotherapy have achieved remarkable success in treating chronic pain. Techniques like hypnosis, behavioral therapy, yoga, autogenic training, and meditation are increasingly popular. Music therapy is also effective, with studies showing that harmonious sounds can bring moments of happiness and reduce the need for painkillers. The pain-relieving power of rhythm, used for millennia in many cultures, is gaining recognition in modern pain management.

Many dentists now offer hypnosis during procedures, helping patients remain calm and relaxed. Deep diaphragmatic breathing warms the body and relaxes muscles. Acupuncture, acupressure, and reflexology—based on traditional Chinese medicine’s concepts of yin and yang and the flow of life energy (qi) through meridians—are also widely used. By stimulating specific points, balance is restored, and pain is relieved. Indian Ayurveda and yoga, as well as European homeopathy, have also shown impressive results, with even skeptics acknowledging their benefits.

Hypnosis: A Promising Approach

Hypnosis offers new and promising possibilities for pain management. This is not the stage hypnosis where people lose control, but a scientific, controlled application used by dentists and surgeons. According to Dr. Dirk Revenstorf, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Tübingen, “Pain management is one of the areas where hypnosis is especially useful.” Across Europe, more dentists are offering hypnosis to patients who request it.

Researchers have found that people with chronic pain significantly improve after six months of music therapy. Under hypnosis, dental drilling and childbirth can be pain-free because, although pain signals reach the brain, they are processed differently and perceived as neutral rather than unpleasant. This is because the usual brain regions involved in pain perception are not activated during hypnosis.

Hypnosis works for about 90% of people, especially those with good concentration and vivid imagination. It begins with calming, monotonous words and focused attention on an object or slow counting. The patient’s attention is directed to a focal point, but hypnosis does not deprive a person of willpower—they remain in control and only reveal what they wish. Complete pain relief is achieved in about 10% of people, those capable of deep trance, but 80% can experience significant pain reduction. Under hypnosis, only a quarter of the usual dose of local anesthetic may be needed for full pain relief.

Self-hypnosis can also help with chronic pain. “Anyone can learn self-hypnosis,” says Professor Revenstorf. “It involves recalling pleasant feelings and joyful memories to counteract pain.” With self-hypnosis, anyone can gain control over their pain.

Based on materials from Reader’s Digest