Principles of Facial Expression Analysis in Short-Term Communication

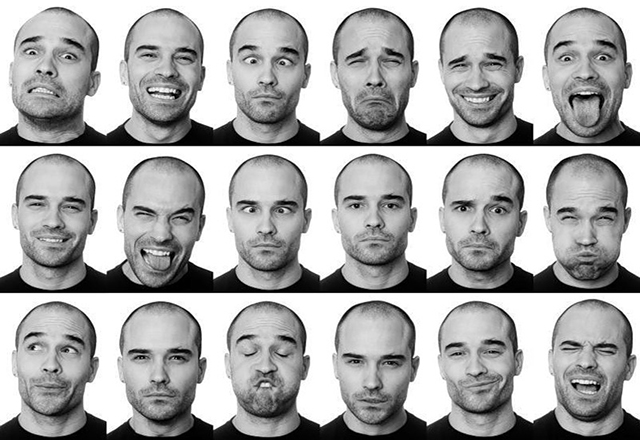

Facial expression analysis, aimed at assessing a person’s reaction to external stimuli or evaluating the functioning of internal appraisal systems responsible for emotional responses, has become widespread thanks to available tools such as the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). FACS allows for the objective description of facial expressions, which can then be interpreted using various methods. Unfortunately, in certain situations—such as short-term communication (for example, during a job interview)—it is not always possible to use the standard FACS algorithm: (1) video recording, (2) describing facial expressions using FACS codes, (3) interpreting the resulting data. Nevertheless, interpreting facial reactions without specialized recording tools is possible, and the information obtained can be significant for decision-making.

Facial expression analysis in short-term communication is based on two principles: maximum objectivity in perceiving the face and the “stimulus–response” principle, where the interviewer evaluates the interviewee’s reaction to a given stimulus (a question or an artificially created situation).

Objectivity in Facial Perception

Objectivity in perceiving the face is impossible without understanding the basic psychological principles of facial perception. These include “perceptual biases” (attempts to link certain facial features with personality traits or behavioral tendencies) and the principle of adaptation to “habitual” facial expressions.

Perceptual biases stem from both the long-discredited field of physiognomy (the ancient system of assessing a person by their face) and the objective influence of facial anatomy on our perception, particularly the width-to-height ratio of the face. The greater this ratio, the more masculine and trustworthy the face appears. This ratio is determined by testosterone exposure in the womb. Studies show that this ratio does not affect behavior or personality, only how others perceive the individual. An interviewer may unconsciously trust someone with a higher width-to-height ratio more, not realizing this trust is based on facial anatomy, not reality.

The same applies to facial dynamics: calmer facial expressions inspire more trust, while hyperkinetic expressions (where there is little or no connection between the experienced emotion and its facial display) can disorient the interviewer, distracting attention from both the face and other behavioral aspects. Adaptation to certain facial expressions is a key principle and can often lead to a loss of objectivity.

A classic example of adaptation is the lack of reaction from relatives to the sad expressions of depressed patients—they become so used to seeing this expression that it loses meaning. Another example is the lack of conscious reaction to expressions of contempt (a sign of dominance) in highly hierarchical or competitive organizations. When adaptation is likely, it is recommended to temporarily shift focus from the face as a whole to specific anatomical markers, which helps quickly restore objectivity.

The “Stimulus–Response” Principle in Short-Term Communication

Using the “stimulus–response” principle in facial analysis during short-term communication is necessary due to the low frequency of significant facial reactions and microexpressions during so-called neutral conversations, which pose no emotional risk to the interviewee. Unlike the classic FACS algorithm, short-term communication uses approaches focused on categorizing and evaluating behavior in real time. It is advisable to combine two approaches to facial expression analysis: the discrete and the componential.

The main proponent of the discrete approach is renowned American psychologist Paul Ekman, who identified seven basic emotions, each with a specific facial expression and functional meaning. Ekman also introduced the concept of “microexpressions”—brief, involuntary facial expressions that reveal true emotions. Facial muscles can contract both consciously and subconsciously, with subconscious contractions being more symmetrical, smoother, and often faster. Microexpressions, lasting only 40 to 200 milliseconds, provide a glimpse into a person’s genuine emotions. Detecting microexpressions in real time without video recording requires special training, and their rarity (on average, in only 2% of observed communications) limits their use in short-term interactions.

However, in interviews using provocative stimuli, the frequency of microexpressions increases. Russian experts M.M. Pelekhaty and E.V. Spiritsa, who developed a provocative approach to information verification, note this effect. Their method is highly effective in short-term communication and involves using provocative questions and statements, evaluating reactions based on discrete basic emotions and their microexpressions. This approach allows for fairly accurate verification of truthfulness. The interviewee is presented with a series of provocative questions designed to elicit specific emotional reactions. For example, if the interviewer expresses belief in the interviewee’s innocence, an innocent person will show joy or even delight, while a guilty person, when believed, will display contempt, relief, or a contemptuous smile. Expressing disbelief to an innocent person provokes surprise and anger, while a liar will show fear, fake surprise, or disgust.

The Componential Approach

The second approach, effective in time-limited situations, is the componential approach to emotion and facial expression formation, proposed by Klaus Scherer in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Scherer’s approach is based on sequentially evaluating events according to several criteria related to the person’s goals and needs, both conscious and mostly unconscious. The appraisal sequence includes four criteria:

- Relevance: Does the event require attention, further consideration, or active response?

- Consequences: How will the event or its outcomes affect quality of life and the achievement of immediate and long-term goals?

- Coping potential: The ability to deal with the event’s consequences.

- Norm compatibility: Does the event align with the person’s values, social norms, and moral standards?

Evaluating an event according to each of these criteria helps understand the meaning of individual facial elements, which is not possible using only the discrete approach.

Conclusion

In summary, the principles of facial expression analysis require an integrative approach and the elimination of perceptual biases to maximize objectivity. This enables the quick and effective use of facial analysis techniques in real time.

Glossary

- Relevance: The event requires attention, further consideration, or active response.

- Coping potential: The ability to deal with the consequences of an event.

- Norm compatibility: Evaluating an event in terms of its alignment with the person’s self-concept, values, social norms, and moral rules.

Author: Mikhail Baev