Honesty Makes Us More Whole Inside: Sincerity and Authenticity Instead of Narcissistic Defenses

False self, a passion for being first, envy, dependence on others’ praise, arrogance, emotional coldness, inability to feel gratitude—these are all traits of narcissists. Yet, behind the sense of omnipotence, haughtiness, perfectionism, and craving for attention (which are all narcissistic defenses), there often lies a burning shame about one’s imperfections, an intolerance of vulnerability, a sense of emptiness, longing for the true self, anxiety, aggression, fear of rejection, and a thirst for closeness that cannot be satisfied—feelings the narcissist turns away from and refuses to acknowledge.

Clinical psychologist Vladislav Chubarov, refusing to demonize narcissists, notes in his book “Perfection That Gets in the Way of Living” (Alpina Publisher) that narcissistic experiences—centered around self-esteem and maintaining it through others’ recognition—are universal and familiar to all of us.

“We all sometimes desperately want to boost our self-esteem, care about what others think of us, and feel ashamed of our imperfections. In fact, narcissism is a necessary part of any personality; it’s part of our ‘default settings.’ Without it, our psyche wouldn’t form, and we wouldn’t be able to defend our boundaries or achieve success. We all went through the so-called narcissistic stage in early childhood—though not everyone, for various reasons (which I’ll discuss below), managed to fully move past it. As a result, for some, narcissistic experiences become central. Many people’s personalities are organized around self-esteem issues, which are based not on internal values but on others’ opinions. This is the narcissistic character, and it shouldn’t be demonized.”

Chubarov suggests thinking of narcissism as a spectrum, which includes:

- a) Healthy narcissism as a sense of self-worth;

- b) Narcissistic defenses that activate in response to painful triggers or repeated blows to self-esteem;

- c) Narcissistic accentuation of character, when narcissistic traits become dominant;

- d) Narcissistic personality disorder as a persistent pattern of behavior and thinking that causes suffering to the person or those around them.

The author addresses his book to anyone who recognizes narcissistic traits in themselves, describing various self-therapy methods to help “reduce narcissistic suffering, decrease dependence on external validation and comparisons, and finally draw pure water from the well of your own authenticity—your true self.”

“Psychotherapists have long debated whether a narcissistic person can truly change on the inside. Some say that issues of self-esteem, shame, and perfection will always remain painfully tense for narcissists, and few ever gain access to their authentic self. Others argue that it’s impossible to predict the dynamics of a particular personality, and in practice, we see many narcissists who have changed. Yes, there may be relapses, but even occasional catharses—when a person manages to touch their authenticity and be themselves without external validation—are very valuable. I hold the second view because I see real people who have become noticeably less narcissistic, either through life events or therapy.”

In the chapter “Narcissus’ Flowers,” he offers techniques for working with the most painful issues for narcissistic individuals: the tendency to compare, idealize, devalue, and rank others; painful competitiveness; excessive perfectionism; boredom with oneself and others; unbearable shame; and seeing others not as autonomous beings but as self-objects needed only to support fragile self-esteem.

We’ve selected an excerpt, “Honesty and Courage Instead of Hypocrisy and Lies,” in which the author examines narcissists’ tendency toward manipulation and small lies, offers ways to rethink this strategy, and reflects on why honesty and sincerity are essential for regaining lost authenticity.

Learning to Tolerate Shame and Embrace Vulnerability

“The ultimate goal for a narcissistic person is to learn to tolerate shame and accept their own vulnerability. To do this, you must face the unbearable, but take steps that allow you to withstand shame each time. It’s like allergy therapy, where a doctor gives the patient increasing microdoses of an allergen over years, allowing the body to gradually adapt. Think of yourself as allergic to shame. If you recognize many narcissistic traits in yourself, your task isn’t to plunge headfirst into your imperfections and fall into despair, nor to hide them from yourself—both are typical narcissistic strategies. You need to move forward, but in small steps. Below, I’ll discuss what those steps should be.”

The Skill of Honesty: A Path to Authenticity

We move from the surface to the depths, and the sixth skill that softens narcissistic tendencies is honesty. Honesty is closely linked to sincerity and authenticity, though many people don’t feel this connection and see honesty as just a behavioral habit. I’ll show you why honesty is deeper and more important than some think.

Narcissistic people often have complicated relationships with morality. Some believe that common morality doesn’t apply to them. They’re convinced they know better than the “obedient herd” and have their own, supposedly superior, standards of honesty. Others follow laws and social rules mainly because they don’t want to be seen as dishonest. The thought of being exposed brings them great shame. Yet, deep down, they believe that if they could get away with it, they’d break the rules for personal gain. Secretly, such narcissists envy “bolder” people who “get away with it,” which leads to resentment and a desire to condemn those people as dishonest. This is how hypocrisy and moralizing arise: I’d like to rob banks but don’t dare, so I tell others I don’t do it because of my high moral standards (which I don’t really believe in). But if there’s a chance to cheat without being caught, the person may well take it. Narcissistic people with this tendency are happy to “cut corners”: evade taxes with gray schemes, cheat on exams, break traffic rules—especially if the risk of being caught is low and the punishment isn’t severe.

Some narcissists, due to magical thinking and grandiosity, feel invincible—like the hero of “Catch Me If You Can”—and may misjudge the consequences. But more often, a narcissist breaks the rules out of fear of failure and a desire to look good at any cost. It’s not easy to stay honest in every situation without internal guidelines. It seems like rules are “for suckers,” especially if following them gets in the way of success.

If you’re narcissistic and don’t understand why you should be honest and follow rules, but you’re ashamed to be or seem dishonest, moral judgments probably won’t help. If they’re not connected to your authenticity, you won’t feel why being honest is “good” and dishonest is “bad.” It’s more effective to start with aesthetic criteria and use your imagination. Maybe you think “cutting corners” and ignoring morality is cool or bold. Try to create a different reputation for some of your actions—ones you’re used to but that society disapproves of. Use adjectives that change your attitude toward the act. Try to see such actions as “uncool,” ugly, or stupid. Here’s how you might do it:

- Someone who used to shoplift as a sport, posting stolen goods online and feeling proud of “beating the capitalists,” eventually noticed her children copying her. She realized that, from the outside, their actions didn’t look like “fighting capitalism” or a “cool life hack,” but just petty theft. There was no single turning point, but several important reflections and conversations led her to see shoplifting in a completely different light.

- Another client, a narcissist, came to me while fighting to regain his driver’s license. Seven years earlier, he’d caused a serious accident by breaking traffic rules, injuring himself and others (fortunately, no one died). Now he drives again, but his attitude toward rules has changed—not out of fear of consequences, but because he realized the importance of following rules for everyone’s benefit. As a narcissist, he’s even proud of his new “achievement”—his personal contribution to road safety.

So, you can change the image of honest and dishonest actions in favor of the former. But how do you explain to yourself why you should be honest and follow rules even when no one is directly harmed? For example, I describe a client in a previous chapter who lies in job interviews. No one has suffered from her lies—she learns new skills quickly. So why shouldn’t she do it?

Here’s my explanation: because you’re not separated from society by an impenetrable wall. You’re part of it. If you want your hidden self to be less lonely, for your authenticity to connect with others’ authenticity, there must be no lies between you and others. A narcissist is stopped from lying mainly by shame. An authentically honest person is stopped by the desire to be with others without feeling guilty for unfair advantages. An honest person feels an internal connection between taxes and the quality of healthcare they receive. They know they shouldn’t run a red light because it makes things worse for everyone—including themselves, since they’re not a unique exception but part of society. “How could I look my kids in the eye?” an honest person asks, refusing to do something wrong. Some narcissists won’t ask this—they’ll say, “Just like before; the kids won’t know about my work shenanigans.” But authenticity accumulates everything in a person, and you can’t “launder dirty money” with one part of yourself and read your child a bedtime story with another. An authentically honest person has a sense of guilt that keeps them from lying or cheating.

So, a narcissistic person prone to lying and cheating should try to act as if they were authentically honest. Even if you don’t feel like it’s “the real you,” trust me—it is. If you manage not to lie, even when it would benefit you, you’ll feel self-respect, pride, and maybe even a sense of unity and wholeness. Many narcissistic people succeed at this, and it’s a habit worth developing.

Honesty will also free you from unnecessary hypocrisy and moralizing if you tend to fall into those traps. When you feel the benefits of honesty from within, you won’t want to harshly judge someone who lied or gained an unfair advantage. You won’t envy them, because there’s nothing to envy: their behavior isn’t “daring, bold, and cool,” but rather awkward, cowardly, and pitiable—because it’s driven by fear. Yes, even when someone seems to pull off a bold scam, requiring nerve or audacity, lying and cheating are always driven by fear. What kind? The same old fear: fear of not succeeding without dishonest methods. That’s all.

When we start to realize that lies harm us and truth makes us more whole and worthy of respect, we begin to see lies we never noticed before.

Pleasing and Manipulation: Hidden Forms of Dishonesty

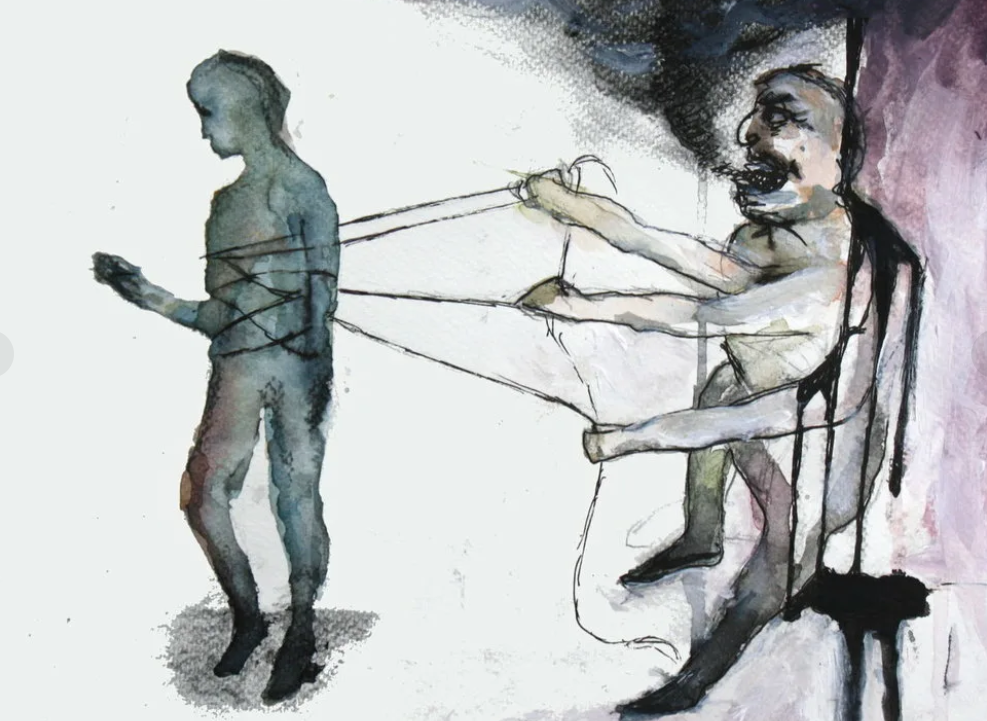

This especially applies to people-pleasing and manipulation, which are everyday strategies for many narcissists. This strategy comes from the habit of comparing and evaluating others and oneself. If you see someone as important and necessary, you may automatically try to please them—earlier, I wrote about the process of attaching to a desired self-object after idealizing them.

“I subtly lead a respected person to think that I’m the one who saved our mutual friend from bankruptcy. I do it skillfully and discreetly. The slight blush on my face is shame for manipulating, while he thinks, ‘What a modest guy.’”

“I casually drop a couple of names, as if by accident, and use some jargon to show I’m in the know. Instantly, I feel my place in the hierarchy rise. The person I see as the team leader immediately recognizes who I am and treats me as an equal. We soar together, while the others are a few floors below.”

“Yes, I do these things too. So what’s wrong with that? Doesn’t everyone like it when people try to fit in with them?” — asks my client Alina. In fact, this question can be rephrased: why is manipulation harmful if it doesn’t hurt anyone? But that’s not quite true.

First, no, not everyone likes it when others try to fit in. In the chapter on idealization, I explained why most people dislike being put on a pedestal as a self-object. The person you’re trying to please feels like a precious vase: you admire them, but they’re just an object to you. The uncomfortable question arises: “Why does this person want me?” Even if your honest answer is “I just admire you,” it’s hard not to protest: I’m not a painting or a monument—I’m meant for human interaction, not to be a tourist attraction. Pleasing doesn’t reach the core: you’re guessing what might please this person, but without close, sincere, open, and lasting interaction, you’ll inevitably miss the mark. There’s nothing that pleases everyone (except maybe money, but that’s why it doesn’t help build real relationships).

Second, pleasing is even more harmful to you than to the person you’re trying to impress. Your interaction becomes about nudging them toward actions that give you pleasure. You secretly direct and control the interaction, making it predictable: you get the reaction you want. When you finally see the person do what you wanted or express the emotion you expected (like being impressed by your knowledge or showing you respect), this living person turns into an automaton in your eyes. You confirm to yourself: “Yes, I pressed the right buttons; I always do; I know how.”

At this point, devaluation increases, because the manipulator feels they’ve used the other person, who didn’t even notice. The other person starts to seem at least naive or simple-minded. Many narcissists believe that if they managed to use someone, that person deserved it. But that’s not true: the narcissist simply acted wrongly. This applies even when “no one was hurt”—that is, no one suffered obvious harm. Some subtle narcissists feel guilt, shame, and regret for acting this way, but the craving is stronger, and they can’t stop. Still, it’s much harder for them to enjoy real, complex, and less obvious live interaction.

Contrary to pop psychology, manipulation harms not the person being manipulated, but the “cunning manipulator” themselves.

It’s like what sexologists say about fetishes. There’s nothing wrong with using fetishes for sexual arousal. But if you love only the fetish (say, a woman’s feet), you end up using the person as an object for your own release. There’s no real meeting of two people. It takes effort to move from using a fetish to enjoying interaction with a partner as a person.

That’s why, in communication, you can’t be guided only by the desire to please. It’s best to create other goals for your interactions and gradually shift your focus from wanting to please to these other aims.