NLP: The Timeline Model

To organize experiences over time, most people arrange images of events along imaginary curves—so-called timelines. Jack McKani estimates that about 20% of people do not use a timeline, though I would subjectively estimate this number at 10-15%. In any case, there is a portion of people who do not use a timeline at all.

Timelines are typically used to determine the sequence of events and to establish cause-and-effect relationships. However, to understand whether an event happened in the past, is happening now, or will happen in the future, a timeline is not strictly necessary—other submodalities can be used. For example, images of the past may appear more faded or gray.

There are quite a few preferences related to how people organize time, such as:

- Ability to plan well

- Rules for establishing cause-and-effect

- Perception of goals

- Habit of dissociating or associating

- Tendency to “overwork”

- “Planning horizon”—how far into the future a person looks

- Adherence to plans and deadlines

- Multitasking

- Orientation toward the present, past, or future

A person may use several types of timelines depending on the context or task. For example, a through timeline at work and an associated one at home.

Types of Timelines

Associated and Through Timelines

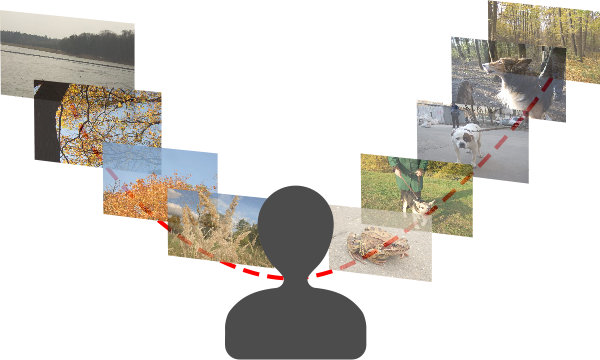

A timeline can pass through a person’s body—this is called an “associated” timeline. If the timeline does not pass through the body, it is called a “through” timeline.

People with an associated timeline tend to:

- Associate with situations

- Multitask

- Get distracted easily

- Place great importance on context (situation determines behavior)

- Not commit to deadlines

- Overwork

- Focus on the present

- Change plans easily

People with a through timeline tend to:

- Dissociate from situations

- Focus on one task at a time

- Plan carefully

- Take deadlines seriously

- Define context themselves (behavior determines situation)

People with an associated timeline usually “move” along the timeline, associating with the events on it. Those with a through timeline observe events “from the outside.”

Timeline Shapes

Timelines can take many forms. Here are the most common:

- For most people, the future is usually located in front, to the right, and upward—in the area of visual construction.

- The past can be in various positions: front-left-up, front-left-down, back-left-down, or directly behind (often for associated timelines).

- The timeline often tilts relative to the horizon, so images of situations are partially visible one after another. If the timeline points straight ahead, a person will only see the nearest situation.

- An associated timeline often appears as an imaginary straight line passing through the chest and directed forward-right-upward.

- Common through timeline shapes include a parabola (future to the right-up, past to the left-down or left-up) or a curved line (future forward-right-up, past back-left-down or back-left-up).

Timelines can also have unusual bends, loops, turns, and tilts. Here are some “non-standard” examples:

- One woman’s timeline was a very wide parabola, so to recall events she had to look far right or left, but her goals and expectations weren’t always in front of her.

- A young man’s future curved behind him to the right, so his “planning horizon” was only about a week.

- Another woman’s timeline spiraled around her body, with past events below and future events above, allowing her to easily compare Augusts of different years, but not Decembers, which were behind her.

- Yet another woman’s future turned left at the end, into the area of visual memories—there she kept images of important goals she couldn’t change (since they were in the memory area) and saw them as inevitable achievements.

Time Orientation

People can be oriented toward the past, present, or future.

- Past-oriented: Images of the past are in front and are brighter and clearer than those of the present or future. They build cause-and-effect from past to present: “In America, politicians have focused on minorities, neglecting the majority, so it’s clear why the majority chose Trump now.”

- Present-oriented: Images of the present are large, in front, and often block images of the future (and past, if it’s in front). They don’t build cause-and-effect, and give information in random order: “Right now, Syria is being bombed, refugees are flooding Europe, Trump was elected, and there’s a movie about the tsar’s affair with a ballerina.” Note: This refers to subjective present, not philosophical present. Subjective present can mean the current situation, the last five minutes, the whole day, etc.

- Future-oriented: Images of the future are brighter and clearer, and the past is often behind. They build cause-and-effect from present to future: “Trump was elected—he wants to bring manufacturing back to America, which means conflict with China, so oil prices will fall.” Remember, the future is different from the past because it can change—while the past is stable for most people, the future is variable and can have several options.

Planning Horizon

The “planning horizon” is how far into the future a person looks. For some, it’s limited to three months; for others, it can stretch twenty years ahead. People with a long planning horizon (five to twenty years) tend to be more conservative than those with a short (a few months to a couple of years) or medium (two to five years) horizon.

Goals on the Timeline

We can place goals outside the timeline—these are things we want to achieve “in principle.” But if we put a goal on the timeline, it means it now has a deadline, and motivation to achieve it is usually higher.

Other Ways to Organize Time

The timeline is not the only way to organize experiences in time. For example, some people use an imaginary calendar, like Google Calendar. Others see events as a set of slides with time labels, both digital (like a date) and analog: “the further in the past, the more faded the image.”

Identifying Your Subjective Timeline

- Regularly repeated action: Recall a simple, everyday action you’ve done many times in the past and will likely do again in the future, like taking a shower, brushing your teeth, or having morning coffee.

- Visualizing the timeline: Imagine this behavior: today, yesterday, a week ago, a month, a year, five, ten years ago. Similarly, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year, three, five, ten, twenty-five, fifty years ahead. Determine your “planning horizon”—how far into the future this timeline extends.

- Submodalities: Notice which submodalities are associated with perceiving the past, present, and future. Look at images from different times in quick succession. Pay attention to color transitions, clarity, contrast, brightness, etc. If differences aren’t obvious, try thinking about how you do this at different times simultaneously—imagine how it was five years ago and how it will be in five years.

- Draw your timeline: Draw a diagram of your timeline and mark time points on it.

Modeling Someone Else’s Timeline

Explore someone else’s timeline and “try it on” for yourself. Pay attention to:

- Location of the timeline in space

- Associated or through

- Tilt of the timeline

- Density of images

- Planning horizon

- Location of goals

- Submodalities of images (size, brightness, movie/slide, clarity, etc.)

Explore and evaluate the pros and cons of this timeline in different contexts.

Editing Your Timeline

- Experiment with your timeline: change parameters and track the pros and cons for different contexts. For example:

- Switch between through/associated timeline

- Future in front or behind

- Change the tilt up/down

- Change the width: closer to or farther from the center

- Planning horizon: three months, six months, a year, three, five, ten, twenty years

- Density of events on the timeline

- And so on

- Return the timeline to its original state.

- Identify the main contexts where you might need different timelines, such as work, leisure, family.

- For each context, construct your own timeline (or use one for all contexts, depending on your preference), evaluating its usefulness and convenience. Do an ecological check.

- Start using your new timeline(s) in the appropriate situations.