A Brief History of Psychoactive Substances: Hard Drugs

The history of narcotics spans many centuries. The use of psychoactive substances was first mentioned by the ancient Sumerians. As early as five thousand years before our era, their writings referenced opium (translated from Sumerian as “joy”). Narcotics were known in nearly all ancient cultures—Ancient Rome, Egypt, Greece, India—and are mentioned by historians discussing civilizations such as the Incas and Aztecs. Even the peoples of the Far North were aware of the properties of such substances.

Opium and Morphine

At the beginning of the first millennium, the popularity of opium in Ancient Rome was extremely high, thanks to physicians who used it to treat certain diseases. The writings of Hippocrates and Theophrastus mention poppy juice. In the 15th century, the first opium-based medication was prescribed to a patient. In every treatise by ancient and medieval healers, only the beneficial properties of opium were described. Medicine at the time was not advanced enough to understand how strong a dependency this substance could cause.

In 1803, morphine was invented as a product of opium processing. The invention of the hypodermic needle by Charles-Gabriel Pravaz in 1853 made its use easier and intensified its effects, as the drug entered the bloodstream directly, bypassing the digestive tract. Additionally, there was a widespread belief that, unlike opium, morphine did not cause addiction, as addiction was thought to be solely a “property of the stomach.” Major outbreaks of morphinism occurred during the Crimean War (1853–1856), the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), and the American Civil War. Since morphine was widely used as a painkiller during surgeries in wartime, soldiers who had been in the infirmary often returned from war addicted to morphine. However, at the time, this did not cause public concern, as it was considered a private case of abuse and was called “soldier’s disease.”

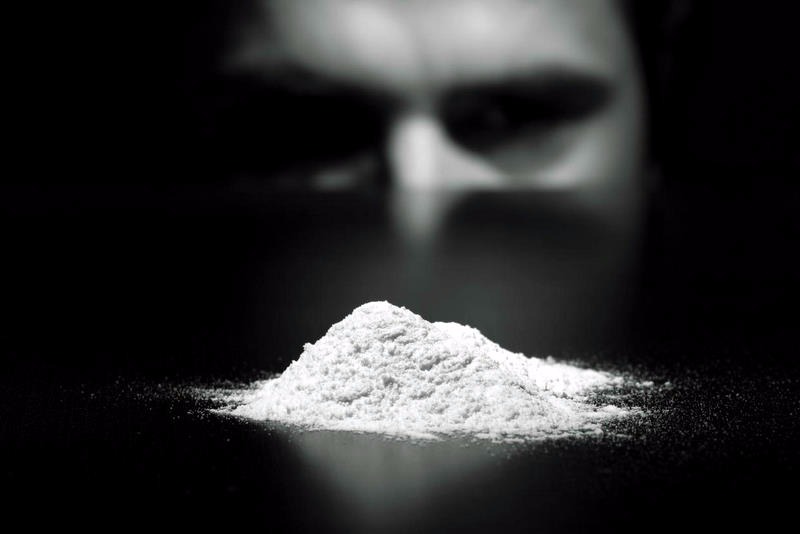

Coca and Cocaine

Drawings by South American Indians have been preserved inside ancient burial complexes, depicting people chewing coca leaves. The word “coca” itself comes from the language of a Bolivian tribe. According to an ancient legend, a local woman led a promiscuous life, for which she was killed and her body cut in half. From her body grew a bush called “Mama Coca.”

Long before the arrival of the Spanish, South American Indians, the indigenous people of the northern Andes, used coca leaves as a psychostimulant for medical and religious purposes, as well as to relieve fatigue, reduce hunger and thirst, and improve mood. In the Inca Empire, coca was specially cultivated. Chewing coca leaves was not available to commoners but was widespread among priests, nobility, and certain state officials. The Incas did not use riding animals, so all urgent messages were delivered by couriers who chewed dried coca leaves to overcome fatigue and increase endurance. Warriors were given portions of coca leaves before long campaigns, which sped up their movement and allowed them to cover significant distances.

As reported in the mid-16th century by official Fernando Santillán to the King of Spain, under the Incas, coca was grown and harvested for the Inca himself and several high-ranking officials. Only after the arrival of the Spanish encomenderos in Peru did coca begin to be given to Indians working on plantations and in mines, sometimes even being used as full payment for their forced labor. The Spanish also forced Indians to gather and harvest coca, leading to mass consumption among the local population starting with the Spanish conquest in 1524.

The Catholic Church tried to ban the use of coca among the Indians. The Second Lima Council of 1567 declared coca chewing a pagan ritual. However, these bans met with protests from the local population and even the Spanish settlers themselves, since coca was one of the main sources of income for the Viceroyalty of Peru, established in 1542, and thus for the Spanish Empire. Starting in 1575, Europeans took full control of the coca leaf trade. In fact, 82% of Europeans in Peru were involved in this sector in some way. Even then, the trade in psychoactive substances was beginning to be regulated.

The active ingredient in coca was first isolated in 1855 by German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke, who named the alkaloid C32H20NO8 erythroxylin. Shortly after, chemist Albert Niemann improved the purification process and named the substance cocaine. Research by Meissner and Wilhelm Lossen determined its exact formula: C17H21NO4. Complete synthesis of cocaine was achieved in 1897.

Cocaine quickly attracted the attention of doctors as an anesthetic. Its psychostimulant properties rapidly made it popular. Until 1906, cocaine was an ingredient in the well-known beverage “Coca-Cola” (the drink owes its name to cocaine). Later, the harmful effects of cocaine abuse became apparent, such as psychological dependence, mental exhaustion, and cases of fatal overdoses. As a result, the circulation of cocaine was restricted and eventually banned.

Heroin

In 1898, the famous German pharmaceutical company Bayer began marketing a new drug—diacetylmorphine, or heroin. Initially, it was offered as a cough remedy. Only 15 years later was it noticed that patients were developing a dependency on it. Today, it is known that heroin is twice as “strong” as its predecessor morphine and even more dangerous.

“New” Drugs

In the 19th century, with the rapid development of chemical technology and organic synthesis, the first synthetic drugs appeared. Amphetamine (alpha-methylphenylethylamine), the most well-known psychostimulant to this day, was synthesized in 1885. In 1919, mescaline (trimethoxyamphetamine), a well-known psychedelic, was obtained in pure form.

During the Vietnam War, American soldiers used amphetamine and cocaine, as they improved performance and relieved fatigue. In the first half of the 20th century, almost all known psychedelics—derivatives of phenylethylamine—were synthesized.