Breaking Russian Laws, But Saving Our Children

While the United States and Canada compete for dominance in the legal drug market, Russia remains on the sidelines. In our country, not only are marijuana producers and sellers prosecuted, but so are users. Even a recent marijuana legalization march in St. Petersburg was ultimately banned by local authorities. Moreover, even producers of industrial hemp face persecution, despite the fact that during Soviet times, the USSR accounted for over 70% of the world’s hemp crops. Experts believe that if the government were to legalize marijuana, life for ordinary Russians would not just become more enjoyable, but also safer and better. The obvious benefits include a sharp reduction in police abuse, fewer cases of drugs being planted on citizens, relief for millions of seriously ill people (including cancer patients), growth in tourism, a boost to industry, and, as a result, the entire economy. Is drug legalization possible in Russia? Why are Russians forced to suffer without it? Find the answers below.

“One Dose Lasts 30 Hours”

Oleg N., a 40-year-old Muscovite, has a special cabinet in his room. Inside, he grows several marijuana plants under a lamp that runs around the clock. A few years ago, Oleg was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a neurodegenerative disease where the immune system attacks nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Depending on which part of the brain is affected, various neurological issues arise. Over time, patients may lose the ability to walk, speak normally, and experience muscle spasms and dizziness. Each patient has a unique set of symptoms.

“I had severe spasticity,” Oleg says. “My arms and legs wouldn’t straighten, especially in the mornings. When they finally did, they would move on their own, jumping and twitching involuntarily.”

At times, Oleg felt completely unable to control his body, unable even to feed himself. Then, he saw a documentary on Discovery about a young foreigner with multiple sclerosis. The man, once a stuntman, could barely walk and suffered from severe tremors. After using marijuana, his tremors almost disappeared, and he began using it two or three times a week. The contrast was striking: a frail, helpless man before, and an impressive athlete after.

Inspired, Oleg discussed it with his wife, who was initially in tears, fearing he’d become an addict. But after a family discussion, they agreed it was the lesser of two evils. “It was my therapy of desperation,” Oleg explains. “The medications prescribed by doctors weren’t helping, and I was getting worse every day. I asked doctors about marijuana, but they warned me not to even think about it. Eventually, one neurologist supported me.”

At first, friends supplied him, but he soon started growing his own, seeking out the best strains from breeders. “If I didn’t feel the effect, I wouldn’t do it,” Oleg says. “One dose lasts me 30 hours. Getting addicted is no easier than becoming an alcoholic.”

Jokes and Jail Time

The scale of drug-related punishments in Russia is staggering: a third of all prisoners—almost 200,000 people—are serving time for illegal drug distribution, and according to research by the European University at St. Petersburg, every third is guilty specifically of possessing marijuana at home.

Technically, Russia allows the cultivation of 20 varieties of hemp (listed in the state register of breeding achievements). This is so-called industrial hemp, which has no narcotic properties and is used in the textile and food industries. Half a century ago, the USSR led the world in hemp cultivation, accounting for 70% of global crops. But by 2011, hemp farming in Russia had collapsed—factories and equipment were destroyed, and only 1,500 hectares remained, compared to nearly a million during Soviet times.

Experts say the industry was dealt a serious blow by a 1987 decree that criminalized the cultivation of hemp on private plots. Since then, this useful crop has been virtually banned. Today, even growing or possessing industrial (non-narcotic) hemp can lead to criminal charges. Russian law includes “cannabis, marijuana” in the list of banned substances, but does not clearly define the term “cannabis.” This legal ambiguity means law enforcement often cannot distinguish between industrial and narcotic varieties, leading to wrongful prosecutions.

Until a clear method for differentiating strains is developed and cannabis is moved from the list of completely banned substances to the list of restricted ones, it will remain easy to be convicted of drug offenses in Russia—even if you’re just a user or caught with a small amount.

“Certain Psychological Changes”

Arrested individuals are often charged with drug dealing (Article 228.1 of the Russian Criminal Code), only to have the charge reduced to possession in exchange for a bribe. Law enforcement officers have been known to organize drug dens and sell doses themselves, sometimes in collusion with drug dealers. Most often, police seize just over the minimum amount needed to open a criminal case—about six grams of marijuana. Natural cannabinoids—marijuana and its derivatives—are the most commonly seized substances, found in 33% of cases, or about 68,000 Russians annually.

Experts say the issue of marijuana legalization in Russia is not just a medical one. The head of the Main Directorate for Drug Control, Andrey Khrapov, stated that the Ministry of Internal Affairs is categorically against legalization, even for medical purposes. “For every disease where marijuana could be used, there are many pharmaceutical alternatives that are safer and more effective. Marijuana use causes dependence and, with prolonged use, certain psychological changes,” he said. He also claimed that in countries like the Netherlands, Uruguay, and Mexico, where marijuana is legal, “human rights activists and reasonable people conclude that legalization was a wrong and unnecessary decision.”

The Marijuana Mecca: Lower Crime and More Revenue

Official Russian data is misleading: more than 50 countries have decriminalized the use, possession, cultivation, and sale of marijuana, including for medical purposes. The Netherlands is famous for its regulated marijuana market, where you can legally smoke, eat edibles, or buy seeds for home growing. Uruguay was the first country to fully legalize marijuana in 2013, and since 2017, it’s been sold in pharmacies to registered locals. Fears of increased crime did not materialize; in fact, drug-related crimes dropped by 20% in a year.

In the U.S., recreational marijuana is legal in nine states and Washington, D.C. California, in particular, has become a new paradise for marijuana enthusiasts, with entire towns being bought up to create a “marijuana mecca.” Studies in U.S. states bordering Mexico showed that legalization reduced crime rates, as Mexican cartels were previously the main suppliers. Similar results were seen in Germany, where prohibition—not legalization—led to more crime.

Although marijuana remains federally illegal in the U.S., the economic impact of decriminalization is significant: in the first year alone, Colorado and Washington added about $80 million to their budgets, thanks to new jobs, tourism, reduced crime, and bringing the black market into the open. Tourism to “marijuana-friendly” centers soared, with California seeing a 200% increase and Massachusetts 1,000%. Colorado hotel bookings rose by 75%. By 2017, Colorado expected to add $230 million to its budget, much of which was invested in healthcare and education.

Many countries have already taken steps toward legalizing soft drugs, including the Czech Republic, Austria, Portugal, Australia, and even Georgia, which decriminalized marijuana use last year. Canada is set to legalize soft drugs this year, which may boost tourism. China has also become a marijuana superpower.

However, Russian authorities may be looking to Southeast Asia for inspiration, where, until recently, drug possession could result in the death penalty (now replaced by life imprisonment in places like Thailand).

“We’re Taking Risks, But Saving Our Children”

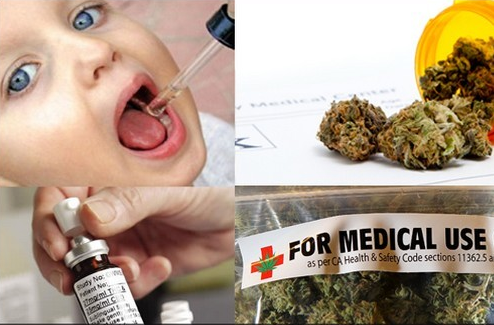

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cannabidiol (CBD)—one of the active compounds in cannabis that is not psychoactive—is beneficial for treating epilepsy and in palliative care. It does not cause addiction and carries minimal health risks compared to conventional medications.

Medical marijuana has been legalized in many countries, including Canada, some U.S. states, the Netherlands, and Israel. Research is ongoing into its benefits for conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, and other serious illnesses. In oncology, marijuana is used to ease chemotherapy side effects, especially nausea. It also helps lift the mood of those suffering from depression—not because it makes them “high,” but because its active compounds affect different areas of the brain.

“My four-year-old daughter has epilepsy,” says Olga from Tatarstan. “She has 5-6 seizures a day and is severely developmentally delayed. I read that cannabis is used abroad to treat epilepsy with positive results. But in Russia, doctors just roll their eyes and tell us not to even think about it.”

Olga says it’s impossible not to think about it when you see your child suffer daily, especially after reading about miraculous recoveries abroad. “In America, one marijuana-based drug is called ‘Charlotte’s Web,’ named after a girl who almost overcame one of the most severe forms of epilepsy. In Russia, many parents of children with epilepsy, desperate for help, experiment. Some move to countries where cannabis is legal. Others buy marijuana-based medications abroad through intermediaries. Many see positive results. We share our experiences on forums. I know we’re taking risks. Maybe we’re breaking Russian laws. But we’re saving our children, whom Russian hospitals have given up on. And marijuana really helps them!”

Neurologist and medical director of the “Family” clinic network, Pavel Brand, agrees that medical marijuana is a clear global trend, mainly used for pain relief. Compared to opioids, it does not cause overdose or addiction. However, in Russia, official medicine avoids discussing cannabis, as doctors fear being caught up in anti-drug campaigns.

“In our country, even the issue of legal opioid painkillers is unresolved—less than 5% of those who need them receive them,” Brand told Lenta.ru. “So we need to sort out the drugs that are not technically banned first, and only then address cannabinoids. In my view, it’s a complex issue. But since the circulation of medical narcotics in Russia is regulated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, not the Ministry of Health, I’m afraid the chances of cannabinoids being used here anytime soon are close to zero.”