Introduction to the NLP Meta Model

The first topic to explore in an NLP course is the language model, also known as the meta model. This model laid the foundation for all further research in the field and led to the creation of an entire branch of practical psychology. The meta model helps us better understand human speech, since we rarely communicate our thoughts with absolute precision. We often leave things unsaid, assuming they are obvious, or unintentionally distort information. As a result, our conversation partner—unless they are a psychoanalyst or psychotherapist—may not always understand us correctly. Likewise, we may not fully understand others. The NLP language model offers tools and therapeutic techniques to help us understand people better and, in some cases, even change their perception.

Brief History of the Meta Model

NLP emerged in the early 1970s as a collaboration between linguist John Grinder, then an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and psychology student Richard Bandler. Together, they studied the methods of three successful psychotherapists: Fritz Perls (founder of Gestalt therapy), Virginia Satir (renowned family therapist), and Milton Erickson (famous hypnotherapist).

In the 1960s, Grinder spent years studying transformational grammar—the science of how deep structures (at the level of the nervous system) are encoded and transformed into language (at the linguistic level). By 1975, Grinder and Bandler developed their own psychotherapeutic language model by modeling the techniques of Perls and Satir. They noticed that these therapists used specific sets of questions to gather information and help clients reorganize their inner world. Drawing on their linguistic expertise, Grinder and Bandler created the meta model, which can be used for effective communication, accelerated learning, personal change, and life improvement.

The prefix “meta” comes from Greek, meaning “beyond, above, about, at another level.” The meta model defines how we can use language to clarify experience, reconnecting a speaker’s words with the underlying experience. Let’s take a closer look at what the meta model is.

What Is the Meta Model?

The meta model of language is an NLP technique that uses specific clarifying questions to help you better understand your conversation partner.

The main presupposition in NLP is “The map is not the territory.” Here, “territory” is a metaphor for “truth” or “objective reality,” while the “map” is our perception of that reality. No matter how skillful the map, it never fully matches the territory. Everyone has their own map, and the meta model shows how to read—and sometimes even change—someone’s map.

We interact with the world by creating models (maps) to guide our behavior. It’s difficult for one person to fully understand another’s map. Behavior only makes sense when viewed in the context of the choices made possible by that person’s map. Our models help us make sense of our own experience. Rather than judging them as good or bad, we should evaluate their usefulness for effective interaction with the world and others.

The meta model gives us a tool to access the experience behind people’s words. When we speak, we never fully describe all the thoughts behind our words. Even if we tried, our monologue would never end. No verbal description can fully capture our experience. We always have a richer internal representation than we can express. Thus, our descriptions are inevitably reduced. This brings us to the concepts of deep and surface structures.

Deep and Surface Structures

Deep structure is the complete internal experience we try to convey. Much of it is unconscious—some is pre-verbal, and some is beyond what words can express.

Surface structure is the words and phrases we use to express what lies at deeper levels. It arises when we attempt to represent and explain our experience.

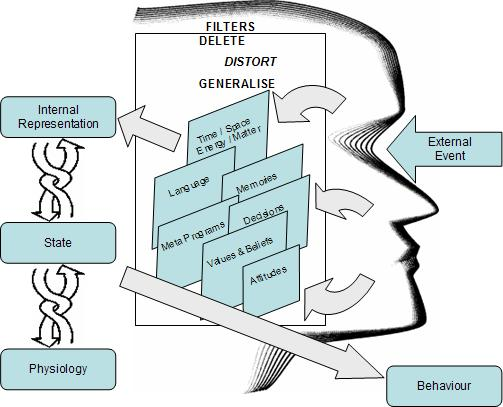

Grinder and Bandler observed that, in moving from deep structures (in the nervous system) to surface structures (in speech), people unconsciously perform three “modeling processes”:

- Deletion: Omitting significant parts of the deep structure when expressing experience or receiving information. The brain receives about 2 million units of information per second, so it must filter out much of it.

- Distortion: Unintentionally altering the structure and meaning of information, changing perception. This ability allows us to enjoy art, music, literature, and to dream and imagine.

- Generalization: Comparing new information to existing knowledge and forming generalizations. This helps us learn quickly, systematize knowledge, and process more data at various levels of abstraction.

The meta model primarily uses these three modeling processes, which describe how we move from deep to surface structures in language. The linguistic markers and questions discussed below will help you analyze surface structures and recover deleted, distorted, and generalized information, guiding the process from surface back to deep structures. This reveals hidden information often crucial for understanding others.

Linguistic Representation of Experience

Here, “representation” means expressing one’s experience through language. As mentioned, people unconsciously use deletion, distortion, and generalization in communication. Understanding and applying these processes can greatly improve communication, enhance understanding, and positively impact your life.

Deletion

Simple Deletions

Occur when the speaker omits information about a person, object, or relationship.

Examples: “I’m scared,” “I don’t know,” “It’s not important.”

Clarifying questions: “What makes you scared?”, “Why are you afraid?”, “What exactly don’t you know?”, “What specifically isn’t important to you?”

Unspecified Comparisons

The speaker makes a comparison without specifying what is being compared.

Examples: “I’m the best,” “Worse than anyone,” “The richest.”

Clarifying questions: “Best among whom?”, “Worse than whom?”, “Richest compared to whom?”

Lack of Referential Index

The specific object or person being discussed is not identified.

Examples: “They won’t come,” “It was better that way,” “What happened there?”

Clarifying questions: “Who exactly won’t come?”, “How was it better?”, “What happened where?”

Unspecified Verbs

The action is described vaguely, making the process unclear.

Examples: “She hurt me,” “They showed,” “I won.”

Clarifying questions: “How exactly did she hurt you?”, “What exactly did he show?”, “How did you win?”

Judgments

Generalized judgments without specific data.

Examples: “That’s not enough,” “Apparently, it’s not serious,” “Obviously, that’s not the case.”

Clarifying questions: “Why is that not enough?”, “What makes you think it’s not serious?”, “On what basis did you conclude that?”

Distortion

Nominalization

Turning ongoing processes into static events by converting verbs into nouns.

Examples: “Relationship,” “Respect,” “Decision,” “Illness,” “Love,” “Education.”

Clarifying questions: “How exactly do I not respect you?”, “What exactly are the problems in their relationship?”, “What did she do when she made the wrong decision?”

Mind Reading

Assuming knowledge of another’s thoughts, intentions, or motives without direct communication.

Examples: “I’m sure he…”, “You know better,” “He doesn’t trust me.”

Clarifying questions: “What makes you sure?”, “Why do you think I know better?”, “What tells you he doesn’t trust you?”

Reverse mind reading: Expecting others to know your thoughts. Example: “If you loved me, you’d know.”

Clarifying question: “I love you, but what exactly should I know?”

Cause and Effect

Assuming one person’s actions cause another’s feelings or behaviors.

Examples: “You make me angry,” “Because of you, I…”, “If you do this, then I…”

Clarifying questions: “How exactly do I make you feel that way?”, “What exactly causes you to…?”, “Why does my behavior affect you so much?”

Reverse cause and effect: Taking responsibility for others’ feelings. Example: “I made him nervous.”

Clarifying question: “What exactly did you do to make him nervous?”

Complex Equivalence

Equating an aspect of behavior with its overall meaning or internal state.

Examples: “You didn’t say hello, so you don’t respect me,” “Coming here was a big step,” “He was late, so he’s irresponsible.”

Clarifying questions: “How does not saying hello mean disrespect?”, “Why do you think coming here was a big step?”, “Do only irresponsible people arrive late?”

Presuppositions

Assumptions that must be true for a statement to make sense.

Examples: “You can work better,” “If only you could understand me,” “I see you’ve changed.”

Clarifying questions: “Better compared to what?”, “What makes you think I don’t understand you?”, “What changes have you noticed in me?”

Generalization

Universal Quantifiers

Words that make sweeping generalizations, implying absolutes.

Examples: “Everyone,” “Always,” “No one,” “All models are dumb.”

Clarifying questions: “Why do you think everyone is in a trance? Are you in a trance? What is a trance?”, “Have you ever met a good non-believer? Can a believer be bad?”, “Have you tested all models for intelligence?”

Modal Operators

Words that reflect beliefs and attitudes, influencing actions and lifestyle.

Examples: “Must,” “Should,” “Have to,” “Want,” “Can.”

Clarifying questions: “What happens if you don’t get a second degree?”, “What if you’re late to the meeting?”, “Why are you sure I shouldn’t do this?”

Lost Performative

Value judgments made without stating their source.

Examples: “A real man must serve in the army,” “What you say is nonsense,” “The many don’t wait for the one.”

Clarifying questions: “Who says a real man must serve?”, “Who decided my words are nonsense?”, “Why can’t the many wait for one? Who made that rule?”

Summary of Linguistic Modeling Processes

Our speech is filled with modeling processes that distort experience. When talking to someone, try to first identify distortions, then generalizations, and finally deletions. Distortions are most apparent in surface structures and have the greatest impact on deep structures. With this knowledge, you can start applying these techniques to better understand others and yourself, improving communication and your life overall.

Applying the Meta Model in Everyday Life

The meta model is a powerful tool for moving from surface structures (language) to deep structures (thought and experience). For effective use, there are seven clarifying questions grouped into three categories:

Gathering Information

- Questions 1: Who? What? Where? How?

Use when information is missing or too general.

Example: “I feel broken,” “Nobody loves me.”

Question: “What makes you feel broken?”, “Who exactly doesn’t love you?” - Question 2: Can you relate this to yourself?

Use to see if the person can apply their statement to themselves.

Example: “He always spoke badly about me,” “They think I’m not good enough.”

Question: “Can you say you always spoke badly about him?”, “Can you say you think they’re not good enough?”

Expanding Boundaries

- Question 3: What stops you? What will happen if you don’t do it?

Use when someone says they can’t, must, or should do something.

Example: “I absolutely must do this,” “I had to see it.”

Question: “What will happen if you don’t do it?”, “What changed because you didn’t see it?” - Question 4: Can you recall situations when you did or didn’t do this?

Use when someone uses words like “always,” “never,” “everyone.”

Example: “I always do this,” “I never succeeded.”

Question: “Can you remember a time you did otherwise?”, “Can you recall a moment when you succeeded?”

Changing Meanings

- Question 5: How did you know?

Use when mind reading is present.

Example: “I’m sure she’ll leave me,” “I just knew.”

Question: “What makes you so sure she’ll leave?”, “How did you know? What exactly did you know?” - Question 6: How did they make you feel that way?

Use when cause-effect is assumed.

Example: “I feel bad for hurting him,” “She’s definitely unhappy with me.”

Question: “Why are you sure he’s hurt? What did you do?”, “Why do you think your actions affect her so much?” - Question 7: Who? Toward whom?

Use when you hear unsupported opinions.

Example: “Her irresponsibility annoys me,” “They acted badly.”

Question: “Who says that’s irresponsible?”, “They acted badly toward whom? According to whom?”

Despite the many theoretical aspects, only seven questions are needed for accurate interpretation. When practicing the meta model, pay attention to your own internal processes, as your judgments may be based on your personal experience, which may differ from your conversation partner’s. To help you master the material, here are some practical tips:

- Apply the meta model to your own thinking. Notice your own patterns and self-talk to identify strengths, weaknesses, and mental blocks.

- Use the meta model in conversations. Formulate your statements based on what you’ve learned to better express yourself and understand others.

- Continue using these questions even after reaching understanding. Over time, this will become a habit and the meta model will become automatic.

- When asking meta model questions, lower your voice and match your tone to the situation. This makes you more pleasant and tactful.

- Don’t overuse meta model questions, as it can harm communication. Use them only when necessary.

- Be clear about why you’re asking questions. Sometimes understanding can be reached in other ways, but always listen carefully and compare what you hear to the meta model.

- When you need precise information, use the meta model gently, as if you know nothing about it—ask simple, even childlike questions.

- Know what you already know and what you don’t. Pay attention to your feelings—irritation, discomfort, caution—as these are clues for effective communication.

- Develop intuition for moments that need clarification. This saves time and helps you get to the heart of the matter.

- Pay attention to your partner’s tone, repetitions, and word connections. These are indicators for understanding. Relate them to what you’ve learned and act accordingly.

By mastering the meta model, you can gain deeper insights into yourself and others, leading to more effective communication and a better quality of life.