How the Mind of a Serial Killer Works: How We Differ from Them

We often call the most terrifying criminals—such as serial or mass murderers—“inhuman.” While this may seem like a metaphor, it also hints at a biological difference. There’s a sense that something about these criminals is fundamentally not right, not quite human.

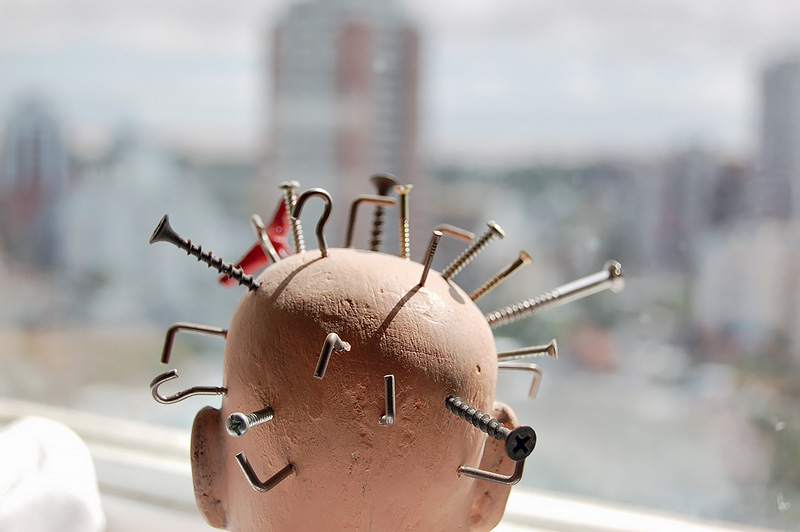

Reading the Skull

Austrian physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) created the field of phrenology, believing he could determine which parts of the brain were responsible for various mental abilities. He thought these abilities were reflected in the shape of the skull, so by examining a skull, one could supposedly tell if someone was a potential Mozart or a potential Jack the Ripper. In fact, the skull was considered more important than the brain itself. Even in his own time, Gall was a controversial figure, and his theories and fascination with skulls were criticized. However, Gall did have the brilliant insight that intelligence is linked to the frontal lobe of the brain. Phrenology itself, though, did not prove effective in identifying socially dangerous individuals.

Comparing to a Psychopath

The basic method for identifying a neurophysiological predisposition to psychopathy is to scan the brain of a diagnosed psychopath and compare the results to those of a healthy individual. The findings are often presented in comparative tables, highlighting the connections between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. A weakened signal from the prefrontal cortex leads to a weak emotional response to things that would horrify a normal person.

In the late 19th century, the controversial Italian psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909) argued that criminal tendencies were physiologically predetermined and sought evidence in physical traits: sloping foreheads, large ears, facial and cranial asymmetry, prognathism (protruding jaws), and unusually long arms. Lombroso believed these features indicated an underdeveloped, atavistic human, close to wild primates, and that such people were destined to be sociopaths and criminals. Lombroso’s ideas and methods were also criticized, but for his time, they were not considered exotic or marginal. His contemporary, Francis Galton, a relative of Darwin, developed the theory of “eugenics,” advocating for artificial selection among humans similar to animal breeding—only those with good physical and intellectual traits should reproduce. Those deemed “defective” should be excluded. These remained theories until the Nazis came to power in Germany and began implementing such ideas. After the defeat of Nazi Germany and the exposure of their crimes, discussions of the biological basis of antisocial behavior became taboo in Europe, and the prevailing view became that criminals are shaped by social environment, troubled families, and childhood trauma.

Prison Science

Since Gall and Lombroso’s time, science has advanced greatly. We’ve learned about genes, and neurophysiology has made significant progress. The question of whether a biological predisposition to horrific crimes is “wired in” could not be ignored forever.

Adrian Raine, one of the founders of neurocriminology, detailed his research in the book “The Anatomy of Violence,” which sparked much debate. While emphasizing the importance of his work, Raine does not deny the influence of environment on the development of a criminal personality.

In recent decades, the term “neurocriminology” has emerged, referring to the study of brain structures that may serve as a biological basis for antisocial behavior. Special attention is given to the causes of psychopathy—a mental anomaly that deprives a person of empathy and gives rise to traits like cynicism and cunning. This disorder is common among serial killers, for whom taking a life is not a serious moral issue.

Modern researchers, like Lombroso before them, often have to go to prisons—not to serve time, but to be closer to the subjects they study. In the early 1980s, British neurocriminologist Adrian Raine spent four years working as a psychologist in two maximum-security prisons. The ideas he developed there were so controversial that he couldn’t get research grants in tolerant England, so in 1987 he moved to the United States, where research into the biological basis of crime was more accepted and there was more material to study. Crime rates are higher in the U.S. than in Europe, and there are more prisons.

Falling from a Cherry Tree

Studying the physiological causes of psychopathy is crucial for understanding serial killers and other villains, but not all psychopaths are born killers, and not all killers are psychopaths. Some studies show that among repeat murderers, there are people with other types of mental disorders, such as borderline personality disorder. Also, damage to the frontal lobes—a factor in developing antisocial personalities—may not be congenital. For example, serial killer Albert Fish, known as the “Brooklyn Vampire,” was a normal boy until he fell from a cherry tree at age seven and suffered a head injury. Afterward, he began experiencing headaches and became aggressive. At 20, he killed and ate his first victim.

In America, Raine was among the first to use modern medical technology, such as positron emission tomography (PET), to study the brains of criminals. He selected two groups: 41 convicted murderers and 41 law-abiding citizens. PET scans showed significant differences in brain activity, especially in metabolic activity. Structurally, the criminal brain showed underdevelopment of the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for social interaction. These features can result in poor control over the limbic system, which generates basic emotions like anger and rage, as well as a lack of self-control and a tendency toward risk-taking—all traits of a criminal personality.

Brain Explosion

Similar studies have been conducted at various research centers, such as the University of Wisconsin–Madison. A 2011 study presented results of brain scans of psychopathic criminals, showing that psychopathy is caused by a weakened connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, part of the limbic system. Negative signals from the prefrontal cortex do not trigger strong emotions in the amygdala, leading to a lack of compassion and guilt—hallmarks of a psychopathic personality.

Moreover, scientific studies have linked criminal behavior not only to brain structure but also to certain genes. In 2017, Professor Jari Tiihonen of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm announced the discovery of CDH13 and MAOA alleles—the so-called “warrior gene”—in the genomes of people who had repeatedly committed violent crimes.

The monoamine oxidase gene (MAOA) is responsible for producing the “reward hormone” dopamine, but in its mutated A variant, it can be dangerous. People with this gene, when consuming alcohol or drugs, experience a sharp increase in dopamine, which “explodes the brain” and leads to uncontrollable aggression. The CDH13 gene is also linked to harmful behaviors, particularly attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Would life be easier if someone knew they were biologically predisposed to aggression and psychopathic tendencies? Perhaps the principle “forewarned is forearmed” applies here, and the sinister call of nature can be overcome by willpower or corrective psychological training.

The Unfulfilled Psychopath

Does all this prove Lombroso and the eugenicists right? Of course not. Even if a biological predisposition to antisocial behavior exists, it is only one factor in personality development. Other factors include social environment, family situation, stress, trauma, and more. The story of American neurophysiologist James Fallon is interesting in this context. He spent years studying the brains of antisocial individuals. His life changed after a conversation with his elderly mother, who revealed that at least seven murderers were among his ancestors dating back to the 17th century. Fallon scanned his own brain and found all the signs of a hardened psychopath: the same underdeveloped prefrontal cortex and weak connection to the amygdala, just like the brain scans of serial killers. Fallon recalled that in his youth, he may have shown psychopathic tendencies—he was a daredevil, made homemade bombs, stole cars, organized risky adventures, and involved his friends. He was narcissistic and devilishly self-confident. But as he grew older, he became a quiet family man and a successful neurophysiologist. So, there is no inevitability.

Science or Freedom?

Neurocriminological research raises a number of moral, ethical, and even political questions. If certain genetic or neurophysiological traits are definitively declared risk factors, how should society and the state treat such individuals? Will these traits become a kind of stigma, following a person for life and preventing them from pursuing their desired career? Should people with troubling predispositions be forced to participate in personality correction programs to suppress what has become an undesirable gift of nature? From the perspective of individual rights, how ethical is it to “get into someone’s head” in the name of public safety? It’s hard to predict the answers to these questions, but the solution is unlikely to lie in bans or suppressing scientific progress in this area. We will always be interested in who we are and why.