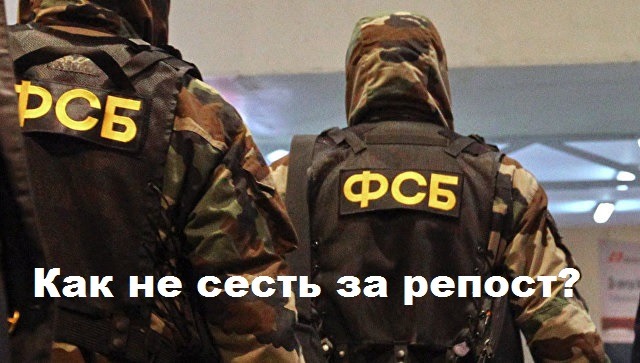

How Not to Get Jailed for a Repost: Open Russia’s Guide

In 2017, it was no longer surprising to hear news about people being prosecuted for their posts online. Jokes about someone being jailed for a “like” or a repost have long stopped being funny—everyone who uses social media knows they could be held responsible for a careless word. Even though the number of “extremism” cases has decreased, people are still receiving years-long sentences for negative comments about Muslims or for sharing images featuring Pushkin and Tesak. Open Russia explains how to avoid such a fate.

What to Watch Out For

First, it’s important to understand which articles of the Criminal Code and the Code of Administrative Offenses are used to prosecute people for posts and reposts. Currently, there are eight such articles—two in the Code of Administrative Offenses (KoAP) and six in the Criminal Code (UK).

In addition, there are several other laws that could theoretically be used to prosecute online posts, though there isn’t much precedent yet. These include:

- Article 354 UK: “Public calls to start an aggressive war”

- Article 319 UK: “Insulting a government official”

- Article 329 UK: “Desecration of the State Emblem or State Flag of the Russian Federation”

- Article 230 UK: “Inducing the use of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances or their analogues”

- Article 110, part 2, point d UK: “Incitement to suicide” (the so-called “death groups” amendments)

In the KoAP, Article 6.21 (“Propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships among minors”) is usually applied to LGBT communities, but sometimes individual people are targeted as well.

Administrative offense cases are handled by district courts. For Articles 20.3 and 20.29 of the KoAP, almost no evidence is needed—screenshots of your page and proof that it belongs to you are enough. Requests are sent to the social network’s administration; for example, VKontakte always responds to law enforcement inquiries.

Article 20.3 KoAP covers posts with swastikas (or symbols resembling them “to the point of confusion”) or emblems of other banned organizations (like the National Bolshevik Party). To be prosecuted under Article 20.29 KoAP, you need to post something included in the Federal List of Extremist Materials; in this case, the case file will also include a statement that the information you shared is banned in Russia.

It’s worth noting that sharing something from the extremist materials list doesn’t guarantee you’ll be prosecuted under Article 20.29 KoAP. It could be treated as a criminal offense, as in the case of 40-year-old mechanic Timofey Komarov from Siberia. Legally, this shouldn’t happen, but this is Russia.

The content of the “extremist” articles in the Criminal Code is a bit more complicated—according to the head of the Presidential Human Rights Council, the very concept of extremism in the law is vague. Let’s look at statements that definitely fall under these articles, using the example of the harmless Moomin trolls.

According to the guide “Afraid of Being Prosecuted for Extremism Online?” by the SOVA Information and Analytical Center, Article 282 UK can apply to harsh statements about religious ideas, national customs, or statements about groups of people united by nationality, religion, or other characteristics.

Calls for extremist activity (Article 280 UK), according to SOVA, include any hints at the desirability of a coup, terrorism, inciting hatred against groups, calls to create any forceful obstacles to authorities, or to commit any crimes motivated by hatred toward a group.

Calls for separatism (Article 280.1 UK) are understood as any statement about the desirability of reducing the territory of the Russian Federation. Justifying terrorism (Article 205.2 UK) can be considered any claim that terrorist acts as a method are justified.

Article 148 UK—“Violation of the right to freedom of conscience and religion”—is a hybrid of Article 213 (“Hooliganism”) and the “extremist” Article 282. It can cover all crude statements about religion (even the phrase “God does not exist”).

The most famous case under Article 354.1 (“Justification of Nazism”) is the story of Vladimir Luzgin from Perm, who was fined 200,000 rubles for reposting an article claiming that the USSR and the Third Reich cooperated before World War II.

How to Protect Yourself

There are several ways to minimize your risk of prosecution, aside from the obvious “don’t write or repost anything that could be interpreted as extremism.”

The vast majority of criminal cases for online extremism are initiated because of posts on the Russian social network VKontakte. Foreign networks—Facebook or Twitter—do not cooperate with Russian authorities. A few people have been held administratively liable for FacebookFacebook launched an official Tor mirror in 2014, becoming the first major tech company to provide direct access through onion routing. The mirror allows users to bypass censorship, secure their connections, and avoid phishing risks while using the platform. This step also underscored Facebook’s recognition of free expression and inspired other outlets like the BBC and ProPublica to create their own Tor versions. More posts; most likely, there won’t be criminal cases in the near future, since law enforcement needs to prove that you wrote the post, and without a response from the social network, this is impossible.

It’s worth noting that the advice to clean up or delete your page doesn’t always work—if investigators have already opened a case, taken screenshots, and properly documented them, you can be prosecuted even for deleted posts. Still, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Usually, people under investigation for extremism find out during a search of their home. If you’re lucky and learn about suspicions against you before stern men in uniform knock on your door, you’ll have time to prepare.

Defendants in extremism cases are added to the Russian Federal Financial Monitoring Service’s list of terrorists and extremists even during the investigation, before any court decision. You won’t be notified about being added; once you become a suspect, all your bank cards and accounts will be blocked. You’ll likely have a very short window to withdraw your funds, so do it as soon as possible.

The main evidence against you will be an expert analysis of your post or repost, which will almost always find extremism if the investigators want it to. You and your lawyer should order an independent alternative analysis. However, this does not guarantee acquittal—the court may refuse to accept the analysis or simply ignore it.